For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1995 Yamaha YZ250.

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1995 Yamaha YZ250.

|

|

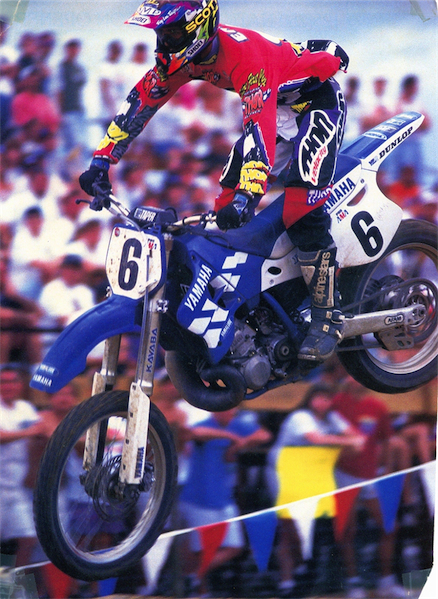

Greg’s 1995 YZ250 is made up to be a Jeff Emig Factory Yamaha replica. When I first saw these bikes in ’95 I actually hated them and thought they looked awful. After a while, however, the blue grows on you and now I think they actually look pretty cool. |

The early nineties were a tumultuous time for Yamaha. After struggling mightily in the early eighties, with subpar machines and dwindling market share. They had come roaring back at the end of the decade with vastly better bikes and hot young talent. With superstar riders like Damon Bradshaw and Jeff Emig in their stable, Yamaha looked to be creating a motocross dynasty for a time. Then the 1992 LA Supercross happened, and Camelot came crashing down. Bradshaw’s crushing defeat at the season finally would send the Yamaha ace into a funk that would force him into a shocking early retirement only a year later (walking away from a multi-million dollar contract in the process). With the retirement of Bradshaw, Yamaha’s hope of finally ending a decade of Honda dominance would go up in smoke.

|

|

The big news on the ’95 YZ250 was its majorly revamped motor. After over a decade of use, Yamaha did away with their YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and replaced it with an all-new design. The new exhaust valve was called ERG (Exhaust Resonance Chamber) and incorporated a chamber on the side of the cylinder to increase exhaust head pipe volume at low RPM (Honda had used a similar system on their ATAC equipped CR250R a decade earlier). The new motor was extremely responsive, with a very wide, easy-to-use spread of power. |

In the midst of all this turmoil, Yamaha was quietly cranking out some of the best 250 machines of the early nineties. While Honda was stealing headlines with their racy CR250R, the slightly dowdy (if you will pardon the pun) YZ250 was ripping holeshots from coast to coast. What the Honda did with raw horsepower, the Yamaha would accomplish with smoothness and finesse. They may not have been glamorous, but the early nineties YZ’s were well suspended, easy-to-ride and stone reliable.

The 1995 Yamaha YZ250 was in the third and final year of its development cycle. Originally introduced in late ’92, the YZ had been a successful design from the very beginning. The ’93-’94 motors had been smooth and rider friendly, with wide power curves and tractable deliveries. This combined with their solid suspensions and stable chassis had made them excellent race bikes. They were basically great do-it-all bikes, which did not dominate in any one category, but also lacked the serious flaws of most of the competition. After taking MXA shootout victories in ’91 and ’92, the YZ250 lost out to the rocket fast, but poorly suspended CR250R in ‘93. Then in ’94, it was the incredibly plush Kawasaki KX250 that beat out the YZ for the class title. For ’95, Yamaha would look to build on the strength of its proven design, to reclaim the title of the top 250 in motocross.

|

|

On the dyno, the new YZ250 mill pumped out a class competitive 44.2 HP. That was shy of the rocket-fast Honda, but better than the mid-range only Kawasaki and Suzuki. In terms of power spread, the YZ and CR were similar, with wide curves that covered all the bases. In the end, it came down to conditions to determine the best overall motor of ’95. In deep loam, the CR’s hard hit and top-end pull gave it an advantage. If the track was dry or slippery, however, the tractable YZ was the bike to beat. |

In 1994, Yamaha YZ250’s were the acknowledged king of the holeshot on the National level. The hot ticket that year was to add “long-rod” kit to the 249cc YZ mill and start cashing your 1-900-PRO-RACE holeshot checks. All told, Yamaha YZ’s nailed about 75% of the starts in ’94 and helped propel Larry Ward to the highest finish ever by a privateer in Supercross. For ’95, Yamaha looked to translate some of that privateer power to their new 250 motocrosser.

While the basic ’95 YZ250 platform was little changed from the previous two years, the one area that got a major revamp was the power plant. Gone was the basic engine design that had powered the YZ since 1983, and in its place was an all-new motor design. The new motor did away with Yamaha’s trademark YPVS sliding drum exhaust valve and replaced it with an ATAC style resonance chamber. The new ERG (Exhaust Resonance Chamber) valve worked similarly to the old Honda set up and boosted low-end power by increasing head pipe volume at low RPM’s. In addition to the new cylinder design, the new motor featured a revised crank with 7% less inertia for a quicker response and a revised intake track. One other big change for ’95 was the switch from long time carburetor supplier Mikuni to Keihin. While the new 38mm Keihin PKW did not produce any more power than the old mixer, its excellent response at lower RPM setting gave it the edge in performance.

|

|

The Factory Yamaha’s in 1995 were a huge departure from the looks of the stock machines. Gone were the cartoon graphics and crazy lavender frame, to be replaced with a serious white and dark blue motif. In 1996, all of Yamaha’s production bikes would move to this new color scheme. |

On the track, the new YZ power plant was the Goldilocks of the 250 class. It lacked the Top-Fuel Dragster horsepower of Honda and the arm-jerking mid-range blast of the Kawasaki, but made up for it with a luscious flow of hooked-up torque that put every ounce of power right to terra firma. In terms of power spread, the new YZ power plant pumped out a long smooth flow of power from bottom to top. It was snappy off idle and very responsive to throttle input. At no point did it explode with a typical 250 two-stroke blast of power, instead it delivered an electric (and very four-stroke like) flow of torque that felt slow, but was actually fast. In deep loam, it was at a bit of a disadvantage to its harder hitting competition, but on hard or slippery surfaces, the YZ would show the competition its taillights. Its only real flaw (aside from some detonation on pump gas) was its notchy gearbox, which had unfortunately become a Yamaha tradition my ’95. Shifting under a load was near impossible without feathering the clutch or backing out of the throttle. Powershifts could be executed with a bit of determination and a heavy boot, but no one was going to confuse the YZ cogbox with a Suzuki or Honda.

|

|

Yamaha’s Kayaba “mid-valve” front forks may not have been as trick as the works style Showa “twin-chambers” in ’95, but carful set up made them every bit the match on the track. They were plush on all surfaces and well sorted for most riders. Fast pro’s complained of harsh bottoming, but for 90% of the riders, the YZ offered the best package of ’95. |

In the suspension department, the YZ250 offered a very solid suspension package in 1995. In the front, Yamaha used Kayaba’s inverted “mid-valve” forks to provide an excellent ride on most surfaces. They were very plush in action, but were a little soft for heavy or expert level riders. With the stock springs installed, they could be bottomed on really big hits and large G-outs. While this was not uncommon for stock fork settings, the real issue was how the YZ handled those hard hits. The mid-valve Kayaba’s transmitted a harsh clunk right to the rider’s hands when bottoming. Thankfully, a swap for stiffer springs and tweaking of the oil level was all that it took to sort out the YZ’s front end. Once that was done, the Yamaha had the best forks of any 250 in ’95.

|

|

Jeff Emig had a solid season in ’95 on the YZ250. He would finish the Supercross series in third place behind Larry Ward (also on a YZ250) and series champ Jeremy McGrath. He would also win his first ever main event in Las Vegas during the infamous night the lights went out. In the Nationals, Fro would go one better, winning Southwick and taking second place in the series standings. In 1996 Jeff would make a move to Team Kawasaki and capture his first 250 Outdoor National Motocross title. |

In ’93 and ’94, the hot setup on the YZ250 was to swap out the stock linkage for a Noleen unit. The Noleen link changed the leverage ratio of the stock YZ suspension and prevented it from hanging down in the stroke under acceleration. For ’95, Yamaha tried to cure this problem by bumping up the low-speed compression and recommending more preload on the shock. It may have been a Band-Aid fix for a poorly designed linkage, but the fine-tuning did a good job of sorting out the YZ’s rear end problems. Like the forks, the stock shock settings were a little too soft for Supercross style circuits. On typical motocross style tracks, however, the YZ was the model of plush performance. Rough chop and acceleration bumps were gobbled up with abandon by the Kayaba rear end. Its only real issue for the average pilot was a bit of “yamahop” on breaking bumps. With so much low-speed compression damping and preload on the spring, the YZ could deflect off sharp square edge holes under breaking. Even with this quirk, however, the YZ250 had the best rear suspension of ’95.

|

The Kayaba rear shock on the YZ250 was plush and smooth in action. It was too soft for pro’s in stock condition, but was the best rear end of ’95 for the unwashed masses. |

If there had been one trait that had been a Yamaha’s claim to fame in the early nineties, it was their stable, easy-to-ride chassis. While the other machines flirted with the far margins of handling performance (Honda and Suzuki-quick turning, but scary at speed. Kawasaki-rock solid on the straights, but a school bus in the tight stuff), Yamaha always played the middle. The YZ was never the razor in the corners that the RM could be, but on the flip side, it was never going to scare the crap out of you on that fifth-gear straight. Much like with the motor, Yamaha took the Goldilocks approach. Not to sharp, and not to slack, just right down the middle.

Well, for ’95, it seemed Yamaha got a little Honda envy, and tried to spice up their middle of the road handler. In an effort to get the YZ to turn better, Yamaha bulled back the offset by 5mm on the ’95 chassis. This little change was supposed to tighten up the YZ’s turning, while retaining its excellent stability, Unfortunately, it did neither (Ironically, Honda attempted to do the same thing in ’94 in the opposite direction, ending up with similar results). In the turns, the ’95 YZ was actually worse than the ’94 had been. It did not feel planted, and was vague at turn in. Its only saving grace was its remarkable low-end response that allowed the rider to dial on the power and snap the rear end around. While this was a disappointment, the real let down was in the stability department. For the first time in a decade, the Yamaha YZ250 was a shaker.

|

|

Starting with the magenta (read pink) ’91 YZ’s, Yamaha’s motocrossers got progressively more colorful every year. By ’94, they were reduced to lavender frames and big lightening bolts on the sidepanels. Although I personally like the looks of the ’95 YZ, there is no doubt that it was a bit cartoony for a serious racing machine. |

The YZ went from being an absolute locomotive at speed, to a ’73 Dodge Dart with bald tires and bad wheel bearings. Worst of all, it did not just pic up a little twitch either. The ’95 YZ shook its head like a dog trying to get rid of flees. It was a high-speed thrill ride that would scare even veteran Suzuki riders (no mean feat this). Dropping the forks in the clamps a bit could help somewhat with the oscillating front end, but that only exacerbated the loose-feeling in turns. Overall, the YZ handling package was useable, but a step back from previous years. Its only saving grace was the fact that none of the other 250’s were without flaws themselves. It was basically a case of pick your poison in the 250 handling sweepstakes for ‘95.

|

|

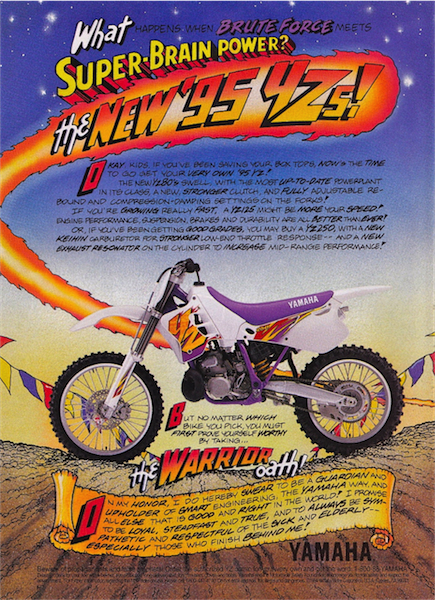

Not only were the graphics on the ’95 YZ cartoony, the ad campaign for it was just as over-the-top. Magazine inserts included a comic book with Yamaha engineers portrayed as super heroes. It may have been silly, but it was certainly memorable. |

Detailing wise, the YZ was near the top of the class in ’95. Nothing fell off or broke unexpectedly, and the quality of most components was first rate. In terms of reliability, the YZ motor was claw hammer reliable and second only to the indestructible Honda for longevity. The brakes were middle-of-the-road in power and feel. They offered less power than the class leading Honda, but far better feel than the spongy and maintenance intensive Kawasaki. It is hard to talk about the ’95 YZ without mentioning the cartoony looks of the bike. I hate to admit it, but this was one of the few bikes from this crazy era that I actually liked at the time. Now, of course, that lavender frame just looks ridiculous, but in ’95 I thought it was pretty sweet. This also being the last of the white YZ’s (before going blue in ’96), I will always have a bit of a soft spot for it.

|

|

I had a 1995 YZ250 and it was a great bike. The motor was torquey, super easy to use and trouble free (aside from an affinity for race gas). The suspension worked great for me and I never even really had any issues with the handling. Aside from the ergonomics feeling a little bit bulky, I thought it was a fantastic bike, and leaps and bounds better than the ’96 model that replaced it. |

In 1995, the YZ250 won both the MXA and Dirt Bike shootouts, based mainly on its solid overall package. It was not the fastest, or the best handling, but its easy-to-ride motor and plush suspension made it the best choice for most riders. In a class full of flawed machines, the YZ’s issues were the least glaring, and that was enough to take the title. In 1996 Yamaha would scrap the ’95 model and crank out an all-new machine that was initially a step back from the one it replaced. Within a few years, however, Yamaha would perfect its blend of smooth torquey power and do-it-all handling, and be ruling the roost, much like the Hondas had done a decade before.