This week Blazier profiles a pretty good bike for Suzuki

This week Blazier profiles a pretty good bike for Suzuki

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1988 Suzuki RM250.

|

|

In 1988, Suzuki introduced a RM250 that for all appearances, looked to be the same machine that had been the 250 class whipping boy for half a decade. Underneath that stale appearance, however, beat the heart of a contender. |

The 1980’s were an interesting time for Suzuki. In most respects, the little manufacturer from Hamamatsu had dominated racing in the seventies. Their Factory motocross team had taken countless World Motocross titles (five 500cc, four 250cc and the first ten 125cc World MX titles ever run) and their production RM’s were widely acknowledged to be the best production machines available. As the eighties began, Team Suzuki was on top.

|

|

In 1987, Johnny O’Mara made the switch to Team Suzuki after a somewhat acrimonious parting with Team Honda. Unfortunately for the O’Show, injuries and sub-par machines would be the hallmark of his first two years on the yellow machines. A healthy Johnny’O and much improved RM would mean much better results in ’89. |

In the early part of the decade, Suzuki was able to continue their momentum with innovations like their remarkable Full-Floater rear suspension system. The suspension on these early-eighties RM’s were night-and-day better than the competition, and more than enough to solidify their position as the leader in motocross technology. With stars like Georges Jobé, Kent Howerton, Mark Barnett and Eric Geboers on the machines, and the best suspension on the track, Suzuki was poised to create a motocross dynasty.

|

|

Moldy Oldie: By 1988, the whole RM line up was in major need of a cosmetic makeover. |

As the decade went on, however, cracks began to show in Suzuki’s dominant motocross program. After floundering with its early eighties efforts, Honda began to turn around its production bike program with greatly improved machines. These DeCoster (The Man had defected from Suzuki to Honda in 1980) developed CR’s quickly transformed Honda from an also-ran, to an industry leaders by 1983. Just as Honda started turning up the heat, Suzuki began falling behind with their bike development.

|

|

In 1988, Suzuki infused a much needed injection of horsepower into their previously anemic mill. A snappy low-end and hard-hitting mid-range made the RM fast and fun. |

By 1984, the early success of their Full-Floater suspension was beginning to fade in the wake of uninspired offerings in every class. The once omnipotent RM125 was still well suspended, but its anemic motor was no match for the powerhouse KX and do-it-all Honda. In the 250 class, the awesome motor of the ’82 RM250 was a distant memory, replaced by a mill more suitable to a leaf blower. Worst of all was the unloved RM500, forgotten and un-updated in three years. In ’81, it had been great handling, but slow. By ’84, it was still great handling, but pathetically underpowered and absurdly out of date. As the decade hit the half-way mark, Suzuki was in major need of a jumpstart.

|

|

With is supple suspension front and rear, the RM was the king of leapers in ’88. |

After a run of subpar RM250’s in ’83 through ’85, and an absolute disaster with the ’86 model, Suzuki finally started to turn the tide in 1987. With the arrival of Bob Hannah and Johnny O’Mara to Team Yellow and a renewed commitment from Japan, Suzuki began the long climb back to respectability with a new RM250 in ’87. While the new RM (unfortunately) looked just like the ’84 model, it offered vastly improved performance over its predecessors. The addition of a true cartridge fork brought it up to snuff in the suspension department, and an all-new motor finally injected some much needed juice into the blue mill. While the RM was not good enough to unseat the incredible ’87 CR250R at the top of the 250 rankings, it won most improved by a wide margin.

|

|

After successful stints at Factory Yamaha and Honda, the Hurricane made the jump to Suzuki in 1986. Hired primarily to help develop the bikes, Bob raced a very limited schedule usually consisting of Southwick and Unadilla. Always frank with his criticism of the machines, Hannah’s input was a key component to the improvement of the RM’s in the late eighties. |

For ’88, Suzuki looked to build on the strides made with the ’87 RM, while addressing the issues riders had the year before. First up, was an all-new pilot’s cockpit, which lowered the center of gravity and allowed better rider movement. The new slimmer and lower tank addressed one of Hannah’s biggest gripes with the ’86 and ’87 RM’s and brought the machine more in line with the ultra-slim ’88 Honda and Yamaha. In addition to allowing better rider movement, the new layout also lowered the radiators a full two inches on the frame for better weight distribution.

|

|

Probably the biggest improvement made to the ’88 RM250 was the redesigning of the rider compartment. A new “low-boy” tank and lowered radiators improved weight distribution. While a longer saddle and slimmer tank profile allowed better rider movement, aiding handing and improving comfort. |

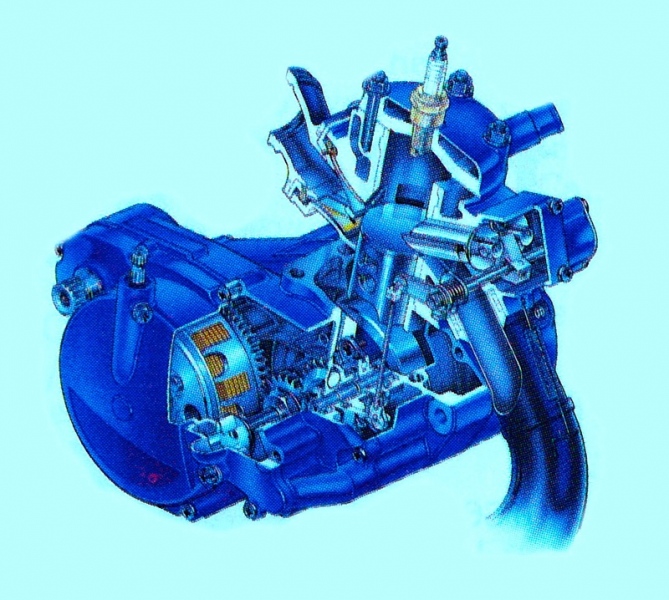

In ’87, Suzuki had spec’d an all-new two-stroke mill that featured the brand’s first usage of a true “Power Valve” to widen the powerband. Prior to ’87, Suzuki had used a variable exhaust resonance chamber built into the head, which worked very similarly to Honda’s ATAC system. For ‘87, Suzuki redesigned their 246cc mill to incorporate a guillotine-type exhaust valve for the first time. The new AETC (Automatic Exhaust Timing Control) valve opened and closed based on engine rpm and functioned similarly in theory to Yamaha’s YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) and Honda’s HPP (Honda Power Port), varying exhaust port height to best suit performance.

|

|

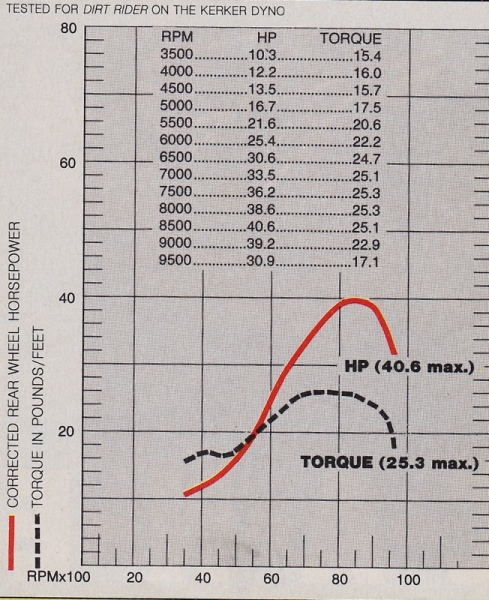

Pump it up: In ’88, the RM made a huge jump forward in the horsepower wars. With motor fine tuning and careful refinement, Suzuki found an additional six horsepower over the mellow ’87 RM. |

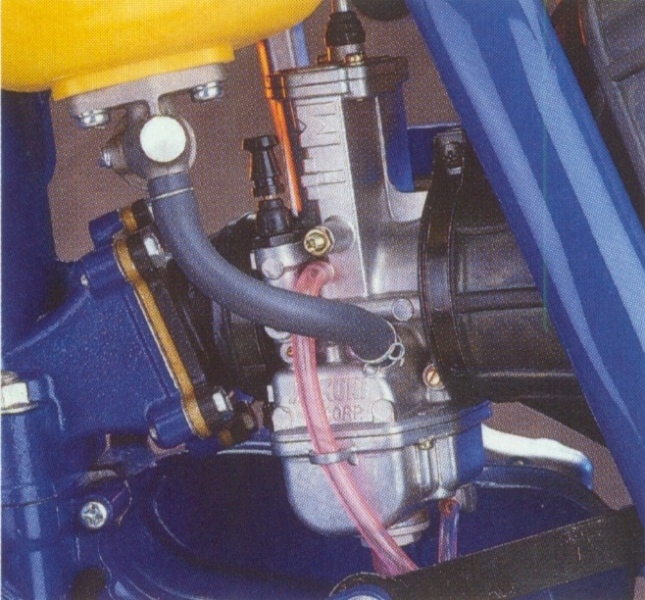

For ’88, Suzuki kept the same basic ’87 mill, but made several refinements to improve power. New porting (1 mm higher transfers), a new AETC valve (T-shaped for better sealing) and a revised exhaust pipe (better ground clearance and increased top-end) were employed to increase performance. Rounding off the motor changes, were a new 38mm Mikuni “slingshot” carburetor (better throttle response and finally an idle circuit), two additional plates for the clutch and a revised gearbox (stronger detents between gears to prevent accidental and missed shifts).

|

|

A huge contributor to the improved powerband on the ’88 RM was the addition of Mikuni’s new 38mm “slingshot” carburetor. The new mixer provided much better throttle response and ran crisply from bottom to top. As an added bonus, the new Mikuni featured an actual idle circuit, a feature sorely missed on the stall prone ’87. |

On the track, the ’88 RM’s power plant was truly in the hunt for the time since the glory days of 1982. Just like ’87, its power was light fly-wheeled and quick revving, with most of its thrust situated in the mid-range. Unlike the ’87, however, this new mill barked out a hard-hitting explosion of power that rocketed the RM out of every corner. Off idle (and for once, it did idle), it was moderately torquey, but no tractor. Once into the mid-range though, it was all fire and brimstone. The RM ripped into a massive mid-range burst that made the bike both fast and fun. After the mid-range, the RM petered out, demanding a new gear to continue the fun.

|

|

Duck-billed: Aside from its unfortunate front fender selection, the front of the RM250 was a thing of beauty. Plush and well controlled, the 43mm KYB’s on the RM were far and away the best silverware in the 250 class. |

Another improvement for ’88 was the RM’s new transmission, which shifted much more positively than previous efforts. In ’87, the RM had been notorious for shifting gears at the slightest nudge of the shifter, resulting in unintended shifts and inopportune false neutrals. With the beefed up clutch and a revised shift mechanism on the ’88, accidental shift were greatly reduced. It was still not quite as positive as the faultless Honda, but a huge step in the right direction.

|

|

“Smoke ‘em if you got ’em“: While Hannah and O’Mara were stuck soldering on with mildly tuned production RM’s, the boys in Europe got to ride the good stuff. The case-reed motor and USD forks off of Rodney Smith’s RH250 would make their way to production on the ’89 RM250. |

In ’88 power sweepstakes, there was truly only one dog in the field. The Suzuki offered the most hit, Yamaha the best response and the Kawasaki the most brute power. Only the once omnipotent Honda left riders wanting in ’88. Its lethargic and listless delivery had longtime Honda riders scratching their heads and wondering where all the ponies went. While all could be ridden competitively, most riders preferred the snappy Yamaha or muscular Kawasaki to the mellow Honda and barky Suzuki. The RM required the most effort to control and the most shifts-per-lap, but it was the most fun motor of the four to ride.

|

|

In 1987, Suzuki spec’d an all new 246cc mill for the RM250. The new motor featured Suzuki’s first usage of a true “power valve” (previous RM’s had used an ATAC style exhaust resonance chamber) to widen the power curve. The new AETC (Automatic Exhaust Timing Control) system used a set of sliding guillotine valve to raise and lower the exhaust port height based on engine RPM. In 1989, Suzuki retire this motor in favor of an all-new case-reed design. |

While the RM’s motor was fun and fast, the true star of the Suzuki’s package was its awesome suspension. In the early eighties, the yellow machines had owned the suspension category with their remarkable Full-Floater suspension system. Its complicated arrangement of levers and linkages was unparalleled at smoothing out the bumps, but it was complicated to manufacture and expensive produce.

|

|

MIA: In the seventies, most MX bikes came with a kickstand. In the eighties, however, this useful (particularity when you consider most motocross bikes are never raced) convenience feature became a dying breed. By the time Bill Clinton took office, kickstands were as dead at the boost bottle and boot gators. |

In 1986, Suzuki made the dubious decision to mothball their critically-acclaimed original Full-Floater design, in favor of an odd eccentric-cam arrangement. This new design was plagued with terrible stiction issues and knocked Suzuki from top-of-the-heap to bottom-of-the-pile in ’86. After the debacle of ’86, Hamamatsu went back to the drawing board for 1987. A new more conventional bottom-link “Full-Floater” (even after the death of the true Full-Floater, Suzuki continued to use the name for several years) was introduced, and while it was not as flawless as the original, it was a huge improvement over the abysmal ’86.

|

|

When is a Full-Floater not a Full Floater? When you copy Honda’s Pro-Link design and slap the old Floater sticker on the swingarm. Copy or not, Suzuki’s version of the Pro-Link was actually superior to the original in all conditions. It offered an ultra-plush action and was the best boinger of ’88. |

For 1988, Suzuki kept the new-look ’87 Floater design, but revised the ratio of the linage to provide a more progressive action. In addition to the new ratio, Suzuki spec’d a new hard-anodized, piggy-back reservoir KYB shock that featured a new dual-stage valving system and a new slightly stiffer spring.

On the track, the new-look Floater performed nearly flawlessly in ’88. It was plush and well controlled over obstacles big and small, with excellent feel and good bottoming resistance. It was by far the best rear end of ’88, with only the excellent Yamaha coming close to matching its silky smooth action. Even for fast riders, the ultra-plush Zook was the hot ticket in ’88.

|

|

Always a threat for the title in the 125 class, Team Suzuki’s Erik Kehoe was never as successful on the big bikes. Kehoe’s 7th overall in the 1988 Supercross standings would be the best 250 finish of his long career. |

In the front, the RM’s 43mm Kayaba cartridge forks were the best available in 1988. They offered adjustable compression and rebound damping (a big deal in ’88) and a plush ride. Overall, they did an excellent job of absorbing the sharp hits and hard jolts common to a motocross track. With the stock springs, they were too soft for fast guys, but for the average Joe, they were spot on.

|

|

Without a fully removable sub-frame, working on the RM was not as easy as a Honda. Did I mention those fenders were butt ugly? |

For Suzuki, the real issue that needed addressed in ’88 was handling. To put it frankly, in the mid-eighties, RM250’s were clankers. Unlike today, where Suzuki’s are considered the gold standard for chassis dynamics, the RM’s of this era were less than awesome in the handling department. They pushed in the turns, and flexed in the whoops like their frames were made of spaghetti. For ’88, Suzuki trier to cure its handling woes by repositioning the steering head .35 inches forward, pulling in the rake one degree and beefing up the head stay to fight chassis flex. This was added to the lowered center of gravity from the new “low-boy” tank and repositioned radiators to give the RM a whole new personality for ’88.

|

|

While Suzuki was certainly making strides in the quality department, they were still a few steps behind the best in ’88. Overall bolt quality on the RM was poor, with many coming in oddball sizes. Items like this old-school style chain adjuster were indicative of the lack of detailing common to the yellow machines of the time. |

For most riders, the biggest improvement in the handling of the ’88 RM over its predecessors was due to its vastly improved ergonomics. The new lowered tank and radiators facilitated much easier movement forward on the machine, allowing the rider to better weight the front wheel in corners. This alone paid big dividends, as the bike felt far surer in the corners than the year before. There was still a bit of a push on hard pack and the bike was in no danger of turning under a Honda, but it was certainly an improvement. Unfortunately at speed, however, the RM was still a nasty handful. When you got into the upper gears, the bikes flexy chassis was still an issue and keeping it on course required a white knuckled grip and an iron constitution. The chassis flex made the bike very unpredictable when attacking the whoops at speed, often leading to sudden, violent swaps. Headshake was also an issue when coming down from speed, although the oscillation was nothing compared to the wet dog shake found on Honda’s of the time.

|

|

By ’88, all the major motocross players had moved to disc brakes front and rear. While the RM’s brakes were decent performers,they were no match for the Honda’s stong and trouble free binders. |

In the details department, the RM was a couple of steps behind the best in the class in ’88. Number one of the list of deficiencies had to be the RM’s outdated looks. Except for its new tank, the rest of the bike looked like an ’86 RM, which looked like an ’85 RM, which looks like ’84…

By ’88, Honda and KTM had offered a removable sub-frame for a full five years; on the Suzuki you got a single removable bar on the side to aid maintenance, boo. Braking was improved greatly in ’88 with the addition of a rear disc, but the RM still lacked the outstanding power and feel of the Honda. Bolt quality and selection were a miss-matched mess on the zook, with odd sizes and easily stripped heads the norm. Items like the vulcanized grips made switching to Scott’s or Oury’s a pain, and most riders panned the RM’s lever shape and feel.

|

|

Back from the brink: In 1988, Suzuki took a major step back towards respectability in the 250 class. At $3099, the ’88 RM cost $300 dollars more than the year before, but for that cash you got improved handling, better suspension, sleeker ergo’s and a whopping six horsepower increase. It was not perfect, but it was the best RM in half a decade and a damn fine racing motorcycle. |

In 1988, Suzuki took a major step forward with their motocross program. After half-a-decade of miserable failures, the RM came roaring back with a hard-hitting and excellently-suspended package. It still looked like a loser, but under that moldy appearance beat the heart of a racer. It was fast, fun and if not for a few handling deficiencies, the best 250 of 1988.