For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at one of the most infamous motocross machines ever built, the Suzuki TM400 Cyclone.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at one of the most infamous motocross machines ever built, the Suzuki TM400 Cyclone.

|

|

When it launched in 1971, the Suzuki TM400 Cyclone looked to be a budget racer’s dream. Great looks, big power and a rock bottom price all seemed to equal an amazing value. Once people rode the bike, however, those dreams quickly turned to nightmares. |

In 1971, Suzuki was sitting atop the professional motocross world. After making their motocross debut some six years earlier with their ill-fated RH65, the little motorcycle manufacturer from Hamamatsu had steadily improved their machines to the point that by 1970, they were building the best works bikes on the planet. Their incredible RH and RN Factory bikes were blazing fast, feather light and trick beyond belief. These early works Suzuki’s were rolling pieces of moto art, crafted from magnesium, titanium and pure unobtanium. With Roger DeCoster and Joël Robert at the controls, the works Suzuki’s laid waste to the competition in 1971, capturing both the 250 and 500 World Motocross titles.

|

|

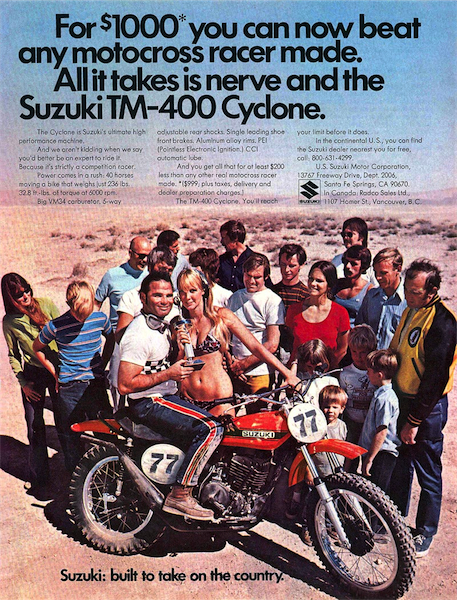

Caveat emptor: Suzuki’s ads for the new Cyclone touted its high tech features, prodigious power and bargain price of $999. Sadly, they neglected to mention its grim suspension, spooky handling and terrifying powerband. |

Hot on the heels of this professional success, Suzuki was eager to move into production their “replica” of DeCoster’s works RN71, the all-new 1971 TM400 “Cyclone”. At $999, the Cyclone undercut the Euro competition by several hundred dollars and certainly looked the part. Suzuki’s press release billed it as a machine for “experts only” and touted it as a legitimate performance alternative to the established Old World brands. Racy styling and a claimed 40 horsepower (a quite prodigious number in 1971) whet the appetite of performance enthusiasts and magazine editors alike. Ads listed its numerous high tech features (Pointless Electronic Ignition (PEI), five-way adjustable shocks and CCI automatic oil injection) and race readiness. On paper, the TM400 looked to be the performance bargain of the decade. On the track, well, that was another matter…

|

|

The 396cc piston-port two-stroke mill on the Cyclone was never lacking for ponies. It barked out a hard hitting explosion of power that twisted frames and tortured knobbies. Even experienced riders found its violent power delivery difficult to manage. |

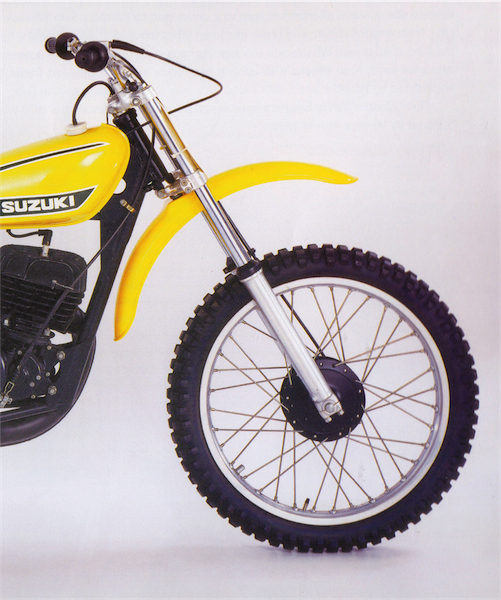

Built from 1971 through 1975, the TM400 was supposed to be Suzuki’s answer to the Maico’s, Husky’s and CZ’s that dominated production Open class racing in the early seventies. At this time, the Japanese had very little presence in the motocross market and were thought of as second tier offerings by serious motocross enthusiasts. Unlike the converted trail bikes offered by Kawasaki and Yamaha, the new Suzuki TM400 Cyclone was supposed to be as serious motocross machine for “experts only”. It featured high-mounted plastic “unbreakable” fenders (a huge improvement over the fiberglass and metal fenders common at the time), full knobby tires, “racing” forks and shocks, a high performance expansion chamber and works bike styling. The styling in particular was outstanding, as the TM looked every bit the RN71 knock-off and far less cobby than most of its competition. Underneath that sexy exterior, however, lurked an overweight, overpowered and under-suspended mess.

|

|

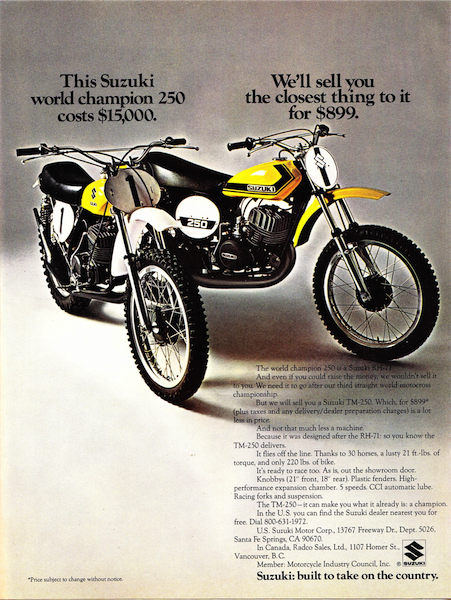

While the TM’s did bear more than a passing resemblance to their works cousins, that was where the similarities ended. In 1971, the production TM400 weighed a staggering seventy pounds more than DeCoster’s works RN71. |

When we look back now, it is easy to see where Suzuki went wrong with their new Open class machine. The bike could have been really good, but cost cutting and poor execution doomed it to failure before it ever began. Put simply, the bike was far too powerful for the chassis it was given and far too heavy for the suspension it was saddled with. It was a 30+ horsepower mechanical bull that could remove its rider faster than John Travolta at an Urban Cowboy convention. It bucked, it swapped and it bounced, until you either came to you senses, or were knocked out of them. If ever a bike fit its name, it was the Suzuki Cyclone.

|

|

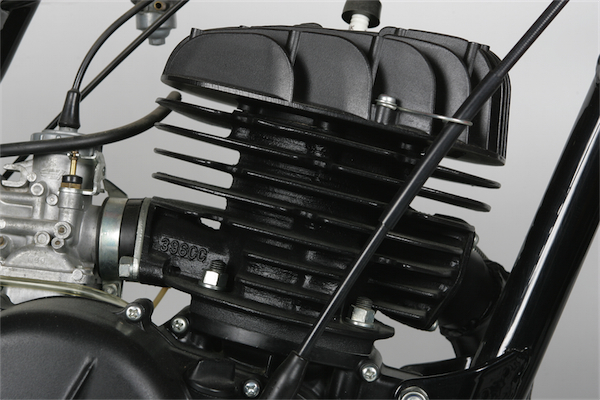

The TM400’s air-cooled mill was extremely simple by modern standards. It had no reed-valve in the intake or variable port on the exhaust, just a big piston and lots of compression. Its sole high tech feature, was its Pointless Electronic Ignition (PEI), which did away with points, but ironically worked less effectively than its old school counterpart. |

So, exactly what made the Cyclone so epically bad? Well, for starters, at 247 pounds ready to ride, the TM400 was extremely overweight and nearly thirty pounds heavier than the best bikes in its class (and a whopping seventy pounds heavier than DeCoster’s works bike). Where the works RN71 had used super light and strong chrome-moly steel for its chassis, the production TM used cheap mild steel to fabricate the tubes. This meant the frame was both very heavy and prone to flexing under stress (always an awesome combination in chassis design). While the use of mild steel allowed Suzuki to keep the cost down, it played major havoc with the TM’s handling.

|

|

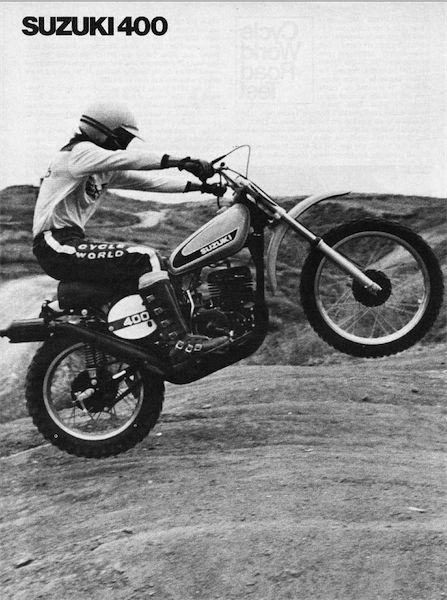

If pigs could fly: With the Cyclone’s prodigious girth and grim suspension, air time was best kept to a minimum. |

Second on the hit parade of the Cyclone deficiencies, was the bike’s rip-snorting power plant. In the King of all understatements, Suzuki’s ads proclaimed the bike’s 40 horsepower “comes on in a rush”. This was certainly true, as the Cyclone ripped through its powerband like Sherman marching through Georgia. The big air-cooled single displaced a mighty 396cc and eschewed any fancy trickery like reed-valves or exhaust gizmos. It was a simple piston-port two-stroke single, just as God and Dugald Clark intended. This was not in and of itself a problem, as many great motors have used this arrangement. Where things went wrong for Suzuki was in the execution of this proven design.

|

|

If you think these two bike have more in common than the color, I have a bridge I would love to sell you… |

One major mistake had been Suzuki’s use of a very light flywheel for the Cyclone. This lack of inertia led to several unfortunate consequences for the Cyclone’s victims. First of those, was just getting the bike going, as its combination of a light flywheel and high compression made the bike a real bear to get lit. Kickbacks were common and of the extremely nasty variety, so only a fool tried to light the TM with anything less than a steel-toed boot. Even if you were lucky enough to get the Cyclone lit before your leg gave out, however, you were far from out of the woods.

|

|

After its first year of production in 1971, the TM400 would be switched from this interesting shade of orange, to the now familiar yellow of the Factory bikes. |

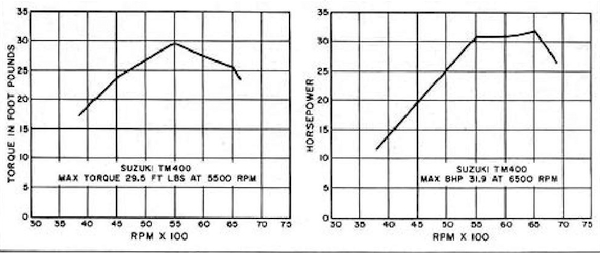

The second problem with the light flywheel was that it exacerbated the TM’s hard-hitting power delivery. Unlike a Maico Open bike, which churned out a steady flow of torque top to bottom, the Cyclone kicked, bucked and coughed down low, before ripping into a mid-range explosion the likes of which not seen since the demise of Pompeii. It was the kind of classic “all-or-nothing” two-stroke delivery that scared riders into taking up bowling and kept ER attendants busy coast to coast. While the TM’s claimed 40hp (actually closer to a real-world 32hp) sounded great, it made all of those ponies in a huge uncontrollable rush. Also compounding the power problem was the TM’s new-fangled PEI maintenance-free ignition. This high tech addition was a major selling point for Suzuki at the time, as it made cleaning and adjusting points a thing of the past. On the not-so-great side, however, was its inability to deliver a consistent spark.

|

|

Powerbomb: With its extremely light flywheel, high compression and erratic ignition, just getting the Cyclone started was an adventure. Once lit, the power started out blubbery, then switched to scorched Earth at a moments notice. |

Put frankly, the PEI system used on the Cyclone was still a few plugs short of a six-pack in 1971. With the PEI, the problem was two-fold. The first of these problems was its tuning from Japan. Because the Cyclone was such a bear to start, Suzuki had set up the PEI to be at full retard for easier starting, and then advance the spark once the bike was going. Normally, you want this to be a gradual process, but on the TM, it was an all-or-nothing affair. Somewhere around 4000 rpm, the ignition suddenly went from full-retard to full-advance and turned the Cyclone from a pussy cat to a pissed off tiger. Exacerbating this problem, were the PEI’s issues with consistent spark advance. Sometimes, the PEI would kick in the afterburners at 4000 rpm and sometimes it might decide to wait another 500 rpm for good measure. It was Russian roulette, motocross style and brave Cyclone riders never knew exactly when that big BANG was coming.

|

|

It may not have been worth a crap on a motocross course, but if throwing roostertails was your thing, the mighty TM400 had you covered. |

In the suspension department, the Cyclone was about what one would expect from a Japanese bike of the era. No bike from Japan had ever come with decent forks in 1971 and the Cyclone was no exception. At the time, the best forks in the world came from Europe, and most Japanese bikes came equipped with silverware stolen off their street bike stablemates. On the Cyclone, this meant board-stiff springs to fight its prodigious girth and a complete lack of damping in any direction. Any track obstacle big or small was transmitted directly to the wrist of the poor TM pilot. If you were unlucky enough to actually bottom the Cyclone’s forks, you could rest assured that they would be rebounding back at you just as fast.

|

|

While Suzuki ads proclaimed a full 40 horsepower from the big single, the true number was closer to 32 hp. Even so, its 32 horsepower (and its very impressive 29.5 pound-feet of torque) made the TM400 was one of the most powerful off-road machines available at the time. |

Out back, the situation was even worse, as the gravitationally challenged Cyclone planted a full 58% of its tonnage to the rear of the machine. This, combined with its substantial power, put a great deal of stress on its spindly twin dampers. If the bike had weighed 220 pounds, they might have been passible, but at 250, it was hopeless. With nonexistent damping and overworked springs, just accelerating was enough to bottom them out and start the Cyclone hopping. With this grim setup, big air and whoops were best avoided at all costs.

|

|

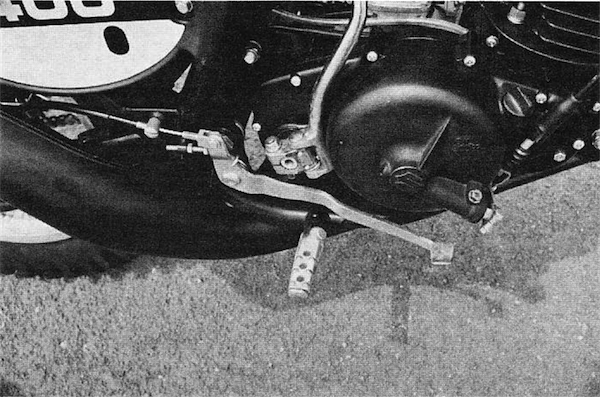

Spindly: This is what passed for footpegs in 1971. Short, narrow, non-spring-loaded and barely serrated, these ankle breakers were marginal at best when dry and completely worthless when wet. |

As with any bike, the proof is in the riding, and on the Cyclone that was a thrill a minute experience. Just getting in motion was difficult, as the bike was no fan of being lugged around at low rpm with its erratic power and light flywheel. There was a razor sharp line between bog and bang and any Cyclone rider worth his weight in plaster quickly learned to straddle it. If you could get going without it hiccupping or stalling, then you were in for a treat as all 32 horses spooled up and transmitted themselves directly to the rear wheel. At this point, several things would happen in quick succession. At the rear wheel, that butter-soft mild steel swingarm would bow and twist, as it struggled to cope with the TM400’s 29.5 foot-pounds of torque. This would in turn bind up the flexy frame like a coiled spring just waiting to go “sprong”! About this time, the frame would release all that energy and Cyclone would attempt to remove its rider by swapping violently with knobbies spinning and shocks hopping, If there was perfect traction, you had at least a prayer of keeping the Cyclone pointed in the right direction. If it was slippery, however, you might as well call your HMO for a referral.

|

|

Stiffly sprung and way under damped, the Cyclone’s forks were better suited to a street bike and virtually worthless in all conditions. |

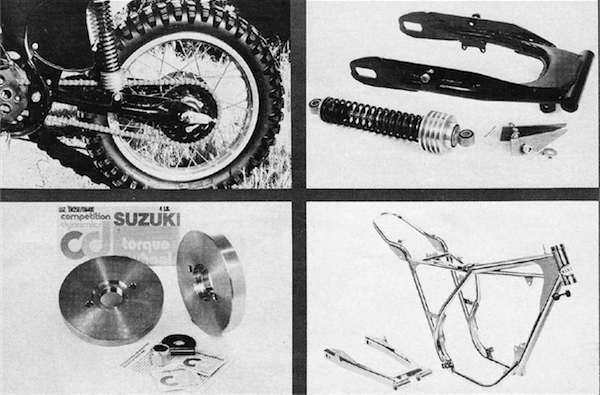

Perhaps the most amazing part about the Cyclone story is that it actually sold quite well. Customers were drawn to (suckered by) its works bike looks and hyperbole laden ad copy and bought the orange (later yellow) tanked menaces in droves. Predictably, this led to a huge demand for aftermarket parts to fix the cantankerous machine. Ignitions (the hot setup was to swap out the PEI for a more traditional magneto), shocks, flywheels and even complete frames were offered to tame the savage beast. By the time you were done fixing all the problems, you could have just bought two Maico’s and been collecting trophies.

|

|

Just as with the forks, the TM’s overburdened rear shocks were of little use taming any kind of difficult terrain. The combination of a hard hitting motor, flexy chassis and over worked suspension made the Cyclone unpredictable in the rough and dangerous at speed. |

|

|

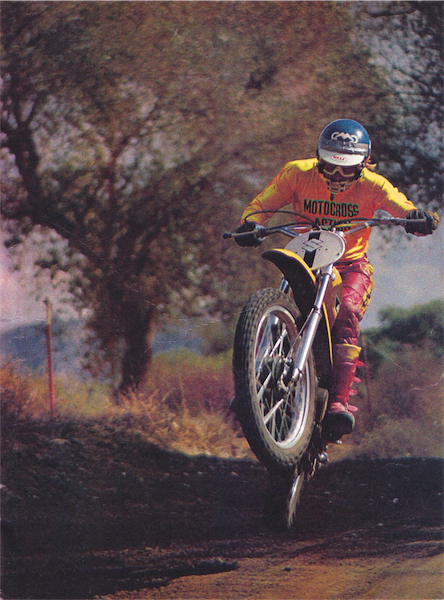

Ye-ha! : Initially, the press was very enthusiastic about Suzuki’s newest baby. At the time, Suzuki was dominating on the track and the TM400 looked quite promising. It did not take long, however, for magazines like Motocross Action to get the word out on the “Widowmaker”. |

|

|

Gold mine: It did not take TM400 owners very long to realize that had been hoodwinked by Suzuki’s promises of a budget priced “works bike”. As a result, fixes for the flawed machine quickly became big business. Shocks, flywheels, ignitions and even complete frames were snapped up in droves in an effort to tame the unruly TM. |

Although word quickly spread about the nasty nature of the Cyclone, it continued to sell well for Suzuki. The bike would remain in Suzuki’s stable until 1975, when it would be replaced by the awesome RM370. Over the course of its five-year run, Suzuki would address many of the bike’s shortcomings. Over time, the power would get less explosive and the suspension would get marginally better. Although it would become less violent, it would always remain a poor handling and badly overweight sled of a machine.

|

|

Injury forces sale: Even today, the TM400 Cyclone remains the poster child for motocross futility. Porky, poorly suspended and absurdly hard to ride, the TM was built to a price, and it showed. With a lot of work and a ton of money, the terrifying TM could be tamed, but never loved. |

So, what do you get when you combine a firecracker, a rubber band and a pogo stick? Well, nothing less than most terrifying and utterly miserable production bike of all time. A 32 horsepower ejecto-seat, with a short temper and a bad disposition. The TM400 Cyclone was a bike so bad, so feared, and so epically terrible, that the mere mention of its name still conjures up visions of twisted metal and tortured bodies. Even forty years later, the Cyclone’s legacy lives on.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier