For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back the 1982 Suzuki RM250Z.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back the 1982 Suzuki RM250Z.

|

|

In 1982, Suzuki took it to eleven with their all-new RM250Z. The new RM featured a blazing fast motor, razor sharp manners and a shock from on High. |

Today’s Suzuki is a mere shadow of the motocross powerhouse it once was. From the late sixties to the early eighties, the little brand from Hamamatsu Japan was arguably the most powerful force in motocross. Long before Honda had even produced its first motocross machine, Suzuki was racking up the World Motocross titles. Roger DeCoster, Joël Robert, Gaston Rahier, Akira Watanabe, Harry Everts and Georges Jobé all brought home gold for Suzuki during this golden age of Grand Prix motocross.

|

|

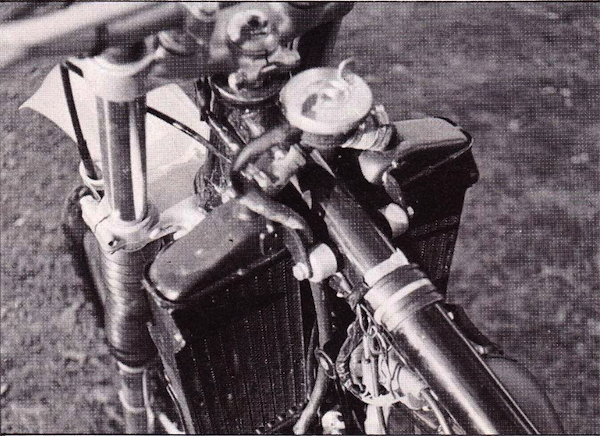

Although initially believed to be unnecessary on a 250 (or 500) two-stroke, liquid cooling really started catching on in the early eighties. Having a more controlled operating temperature range allowed the engineers to run more compression in the motor, more advance in the ignition, and tune the carburation to run cleaner without fear of detonation. |

While their works machines were the best on the track in the early seventies, their production machines left a lot to be desired. Early TM’s were pathetic in most all respects and virtually worthless on a motocross track. Thankfully, all that changed in 1975 with the introduction of the all-new RM series. The RM125, and later RM250 and RM370, were true works replicas and ready to race right out of the crate. After a rough start with the first TM’s, Suzuki had a major hit on their hands with the spectacular RM’s.

|

|

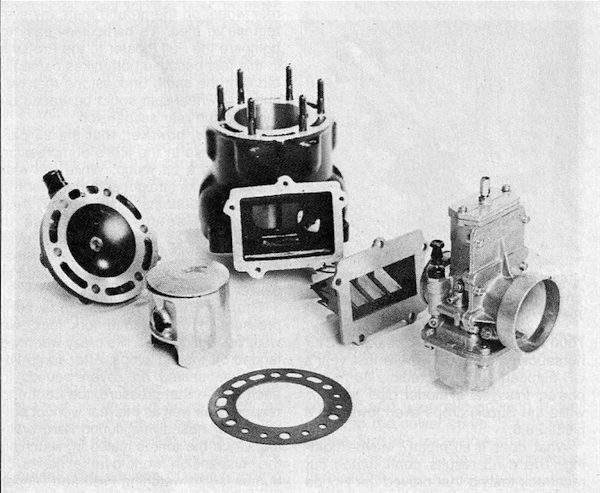

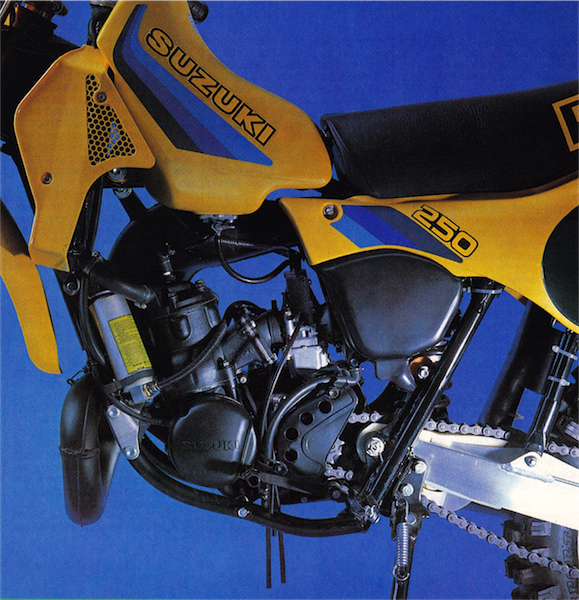

The new liquid-cooled 1982 RM250Z motor retained Suzuki’s unique semi-case-reed “Power Reed” intake design, but dispelled with the separate reed valve for the bottom end. Also new for ’82 was Mikuni’s 38mm TM “flat-slide” carburetor. This high-tech vergaser offered crisper throttle response and cleaner jetting (yay!), but no idle circuit (boo!). |

From its very introduction in 1975, the RM250’s biggest advantage over the competition had been its excellent suspension. In an era where bikes with three and four inches of travel were common, the RM came equipped with nearly double that amount of movement. Even as the other manufacturers upped the ante and moved toward a full foot of movement in the late seventies, Suzuki continued to maintain its lead by delivering the right kind of travel.

|

|

For 1982, Suzuki scrutinized every component on their RM’s in an attempt to deliver the lightest possible race machines. Literally everything was trimmed, hollowed, shaved and machined down to save precious ounces. The result was a liquid-cooled machine that actually weighed 2 pounds lighter than its air-cooled predecessor. At 214 pounds dry, the RM was a full 6 pounds lighter than the next lightest bike (KX250) and a staggering 21 pounds lighter than the heaviest (YZ250). |

|

|

The 250 class of 1982 was an incredibly varied group pf machines offering everything from the simplicity of air-cooling (KX250) to the complexity of liquid-cooling and power-valves (YZ250). |

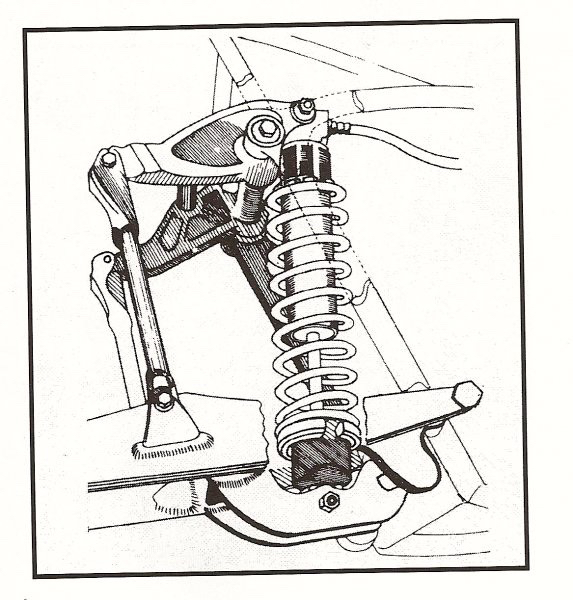

In 1981, Suzuki took the next leap in suspension performance by unveiling its first rising-rate single-shock suspension system – the Full Floater. The Full Floater used a bell-crank arrangement with two pull rods attached to a linkage to compress a single shock from both above and below. The Full Floater name was derived from the fact that the shock was mounted to a linkage at both the top and bottom and was thus “full floating”. The performance of this new suspension design was remarkable for the time and testers came away dazzled with the Floater’s ability to absorb bumps and jumps. It was the best suspension of 1981 by a wide margin and helped propel the ’81 RM250X to the head of the pack.

|

|

Suzuki’s new 246cc mill ditched the long-stroke configuration of the mellow ’81 X-model and replaced it with a quick-revving short-stroke layout. Power was soft off idle, before exploding with a massive rush of ponies that never stopped pulling. In 1982, no other 250 was close. |

|

|

Last Hurrah: Nineteen eighty-two would be the end of Suzuki’s dominant run at the top of the motocross standings. After seven years at or near the top of the motocross heap, Suzuki would slide into mediocrity for most of the rest of the decade. |

|

|

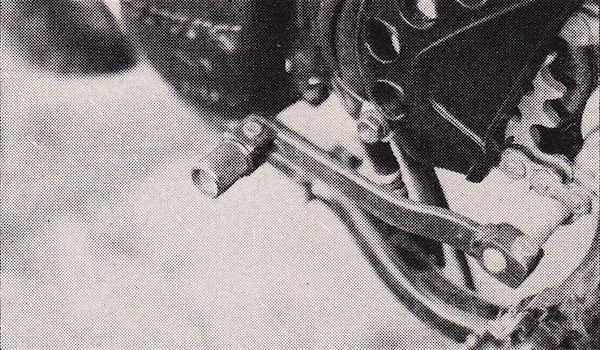

The secret to the RM’s incredible suspension performance was this complex set of pull rods and levers. Unlike a modern MX machine, the original Full-Floater actually articulated at both the top and the bottom, compressing the shock from both sides simultaneously. While it offered incredible terrain articulation and performance, its complexity, cost and high center-of-gravity would eventually doom it to MX history. |

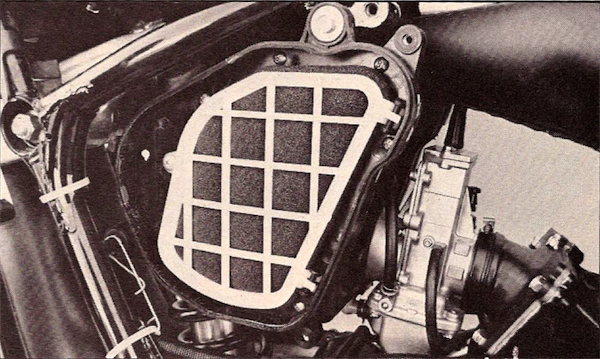

For 1982, Suzuki built on the momentum of their class leading suspension by spec’ing an all-new motor for their quarter-liter racer. The new mill was a radical departure from the mellow ’81 mill and featured Suzuki’s first usage of liquid cooling on a 250cc machine. The all new 70 x 64mm power plant offered a longer stroke than ’81 and bumped up the compression from 8.1:1 to 8.4:1. While it was an all-new design, it retained Suzuki’s unique semi-case-reed intake and mated it to a 38mm Mikuni “flat-slide” carburetor. This new mixer was a big deal in ’82, as it marked the first application of this all-new design. According to Suzuki, the new rectangular slide provided both superior sealing and more even air velocity through the carb’s venturi. Feeding the carb was the same unloved double filter arrangement that had complicated servicing the year before. A new center port exhaust (a first for the RM250) and a redesigned pipe and silencer finished off the motor package

|

|

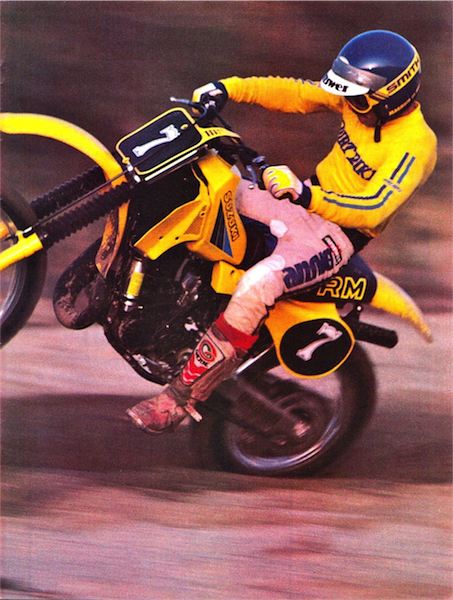

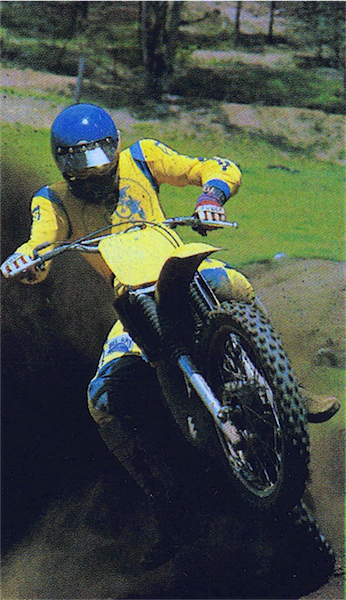

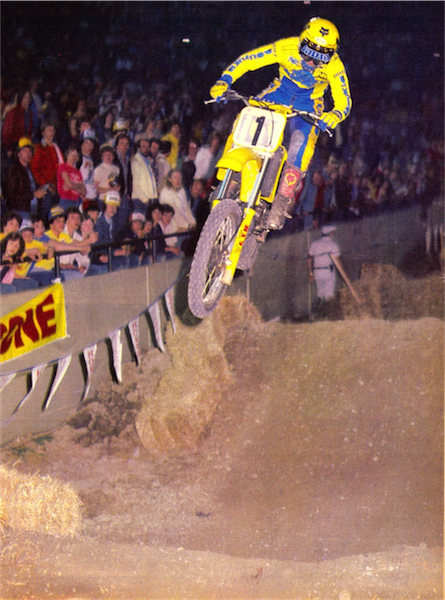

Master blaster: Nothing was as fast, furious or ferocious as the RM250 in 1982. |

In the chassis department, the new water-cooled Z-model retained largely the same dimensions as the outgoing air-cooled X-model. Both bikes shared the same 57.5-inch wheelbase, with the new machine offering slightly less trail (29.3 degrees for the Z vs. the X-model’s 29.5 degrees). The new frame was both lighter and stronger than the ’81 version, with the high strength chrome-molly tubing being trimmed in some areas and beefed up in others.

|

|

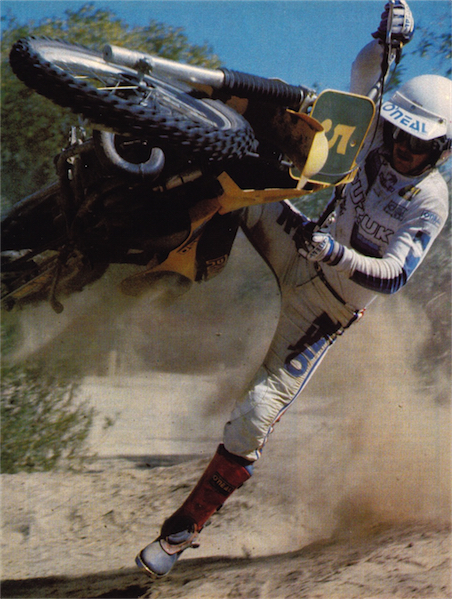

Not spode approved: While its awe inspiring midrange and top-end thrust was loved by pros, less experienced pilots found the RM a bit of a handful. The lack of low-end, light flywheel and sudden on/off nature of the power made the bike a less than ideal mount for newbies. |

For 1982, nearly every part of the RM was placed on a diet. Every piece of plastic was shaved down to be as light and thin as practically possible. Engineers milled and hollowed out every bolt and part they could think of to shave an ounce or two. Both the shock and forks were lighted for ’82, with the forks maintaining a very old school 38mm size in an effort to undercut the weight of the competition. The result of all this care was a featherweight 214 pounds. This made the RM the lightest bike in the class by a wide margin (A full 6 pounds lighter than the next lightest air-cooled KX250 and a whopping 21 pounds lighter than the porky YZ250!) and actually undercut its air-cooled predecessor by 2 pounds.

|

|

BRAAPPP; No berm was safe from the mighty RM250 in 1982. |

On the track, the new RM250Z was an absolute XM missile. It offered both the most power and the least weight of any machine in the 250 class. Power was extremely explosive and fast revving, making it a handful for the inexperienced. Off the line, the RM was nothing special, with little appreciable power below the midrange. Once it climbed on the powerband, however, it was best to pucker up and hold on tight. Midrange power was particularly potent and followed by a streaking top-end that never stopped pulling.

|

|

While the motor was busy stealing all the headlines in 1982, the RM’s amazing Full Floater suspension was quietly cementing its reputation as the best rear suspension system in the business. Like the motor, it was better at charging than cruising, but for hard core motocross, it was impossible to beat. |

On the track, yellow screamer was far and away the best pro motor of ’82. It just kept pulling and pulling until every other 250 was left in its wake. When Dirt Bike tested the stock RM in ’82, they proclaimed it as fast as any works bike they had ever ridden. While its prodigious power made it a favorite of the fast guys, its lack of low end and violent hit made it intimidating for novices. For them, the excellent low-to-mid power of the CR250R was a better choice.

|

|

In 1982, Suzuki was still building some of the most respected works bikes in the business. They had claimed both the 250 National MX title (Kent Howerton) and Supercross title (Mark Barnett) in 1981 and were looking for more success in ’82 with a young George Holland on the team. |

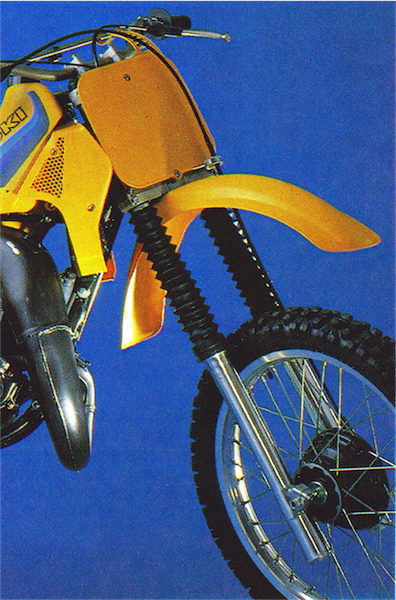

In the suspension department, Suzuki made some interesting choices for 1982. First and perhaps most puzzling, was its decision to eschew the current trend toward bigger and bigger forks and stick with a set of spindly 38mm legs for the RM-Z. By 1982, most manufacturers had moved on to 41mm and even 43mm legs for their full size machines. This provided much less flex and better steering feel in the corners and under braking.

|

|

The one chink in the armor of the 1982 RM250Z was its undersized and poorly set up forks. In an era where beefy 43mm sliders were becoming the norm, Suzuki insisted on sticking with a set of old-school 38mm legs for their 250. This offered a slight weight savings, but came at the price of rigidity. When you combined this vague feel with its wimpy springs and poor damping, you had the worst forks of ’82. |

By sticking with the 38mm tubes, Suzuki chose weight over strength in 1982. Their engineers believed that they could get the same level of accuracy, without the weight penalty, by using a unique double walled stanchion on the bottom of the RM’s forks. In practice, however, this idea proved to be less than ideal.

|

|

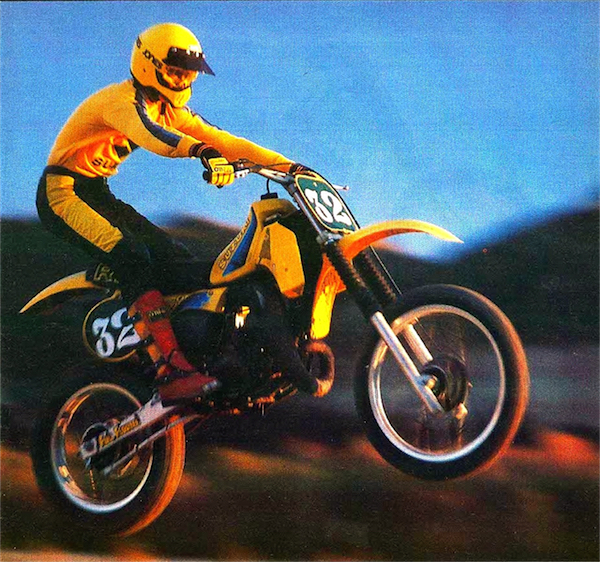

Grabbing a handful was enough to convince longtime Suzuki pilots this was a whole new kind of RM. |

On the track, the RM’s forks exhibited noticeably more flex than the 43mm competition. This gave the front end a vague feel under braking and less accuracy under heavy loads. Travel was competitive at 11.2 inches, but both the damping and spring rates were too light to provide proper control. In stock condition, they dived badly under braking and bottomed with a THUD on hard hits. By adding 7-10 pounds of air to each leg, some of that could be alleviated, but the performance was never going catch that of the other three 250’s.

|

|

After taking the ’81 Supercross title, Mark Barnett backed it up with 4 Supercross wins (tying eventual series champ Donnie Hansen for wins) in the’82 season. Unfortunately, a 15th at Seattle and a 11th at Pontiac would cost him a second Supercross title. |

Out back, the picture was much better with Suzuki’s revolutionary Full Floater single-shock rear suspension. In the rough, the Floater had no peers and could be plowed into obstacles that would leave the other brands floundering. Big-hit absorption was the best of the field and the RM craved to be ridden aggressively. For slower and less aggressive riders, the Suzuki could seem a bit stiff and unforgiving, but for fast guys, the RM was King.

|

|

Due to the size and location of the complex Full Floater system, Suzuki’s engineers decided to use a unique U-shaped airbox for the RM250. Dual filters (one on each side of the bike), combined with Suzuki’s penchant for oddball fasteners and an overabundance of washers made servicing the RM a tedious affair. |

|

|

If you were serious about winning in 1982, you were going to ride one of these two machines. For pros, the RM250Z was the clear choice, but for average Joes, the torquey power and stable handling of the Honda CR250R was a better choice. |

In the handling department, the RM was the king of the inside line in 1982. Its soft front suspension helped the bike take a set in corners and no other bike was capable of carving under the lightning-fast Zook. At speed, the bike could be a handful and the headshake was bad enough to require a Hail Mary or two prior to setting off. The bike’s suspension imbalance only exacerbated this problem and made high-speed runs on the RM a terrifying experience. It was best to wear clean shorts if any fifth gear straights were in your future.

|

|

Relic: With Kawasaki going to a disc and Yamaha and Honda both employing powerful dual-leading shoe drums, Suzuki’s single action front brake was back of the pack for pucker power in ’82. |

|

|

The addition of a folding shift lever was welcome news for 1982. |

In the detailing department, the RM was pretty par-for-the-course for 1982. Both shifting and clutch life were good and the addition of a folding shifter was a welcome addition. The new bodywork was well liked and the overall ergonomics were considered quite good for the time. Riders loved the Z-model’s low seat height (and much less tear-prone new seat), but were less enthusiastic about its leg-roasting stock pipe. Braking performance was likewise panned, with the RM offering the least pucker power of the Big Four. Servicing the airbox was a particularly infuriating affair, with two filters to clean and an inscrutable amount of mismatched bolts and screws to be dealt with. This was still a major problem among all the brands in ’82, but Suzuki was the worst offender in this fastener roulette.

|

|

For Suzuki, 1982 would be one last hurrah, before a run of mediocre 250’s to finish out the decade. By ‘83, the power would be gone and by ’86, the suspension magic would be over, too. Unfortunately, the eighties would prove to be a tough slog for the fans of the once dominant brand. |

In 1982, Suzuki unleashed a pro-oriented weapon on the 250 class. It was feather light, hard hitting and blessed with the best rear suspension ever to grace a deuce-and-a-half racer. It was a hard-edged and unforgiving, but up to the challenge if you had the skill to make the most of its potential. For aspiring Mark Barnett’s, there was no better choice than the RM250Z in 1982.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier