For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first four-stroke motocross machine, the 2002 CRF450R.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first four-stroke motocross machine, the 2002 CRF450R.

|

|

In 2002, Honda unveiled their first production four-stroke motocross machine, the CRF450R. Coming a full five years after the introduction the YZ400F, Honda had taken their time in crafting a response to Yamaha’s revolutionary thumper. The CRF was lighter, leaner and aimed at making four-strokes more accessible to the two-stroke masses. |

Founded in 1948 by Soichiro Honda, Honda Motor Corporation has always been a champion of four-stroke technology. Soichiro himself was famously indifferent to the charms of the oil burners and preferred to focus on small valve-and-cam engines instead. Throughout the sixties, while the other Japanese manufacturers were cranking out two-stroke dirt and street machines, Honda was content to build friendly little four-strokes that were inexpensive and far less fiddly to live with than their pre-mix burning brethren. The Hondas always started, never fouled a plug and generally went about their business in a dependable and unassuming way.

|

|

Long a champion of the four-cycle motor, Honda had started as a four-stroke company and stayed committed to thumpers long after the other Big Four had switched to lighter and more powerful two-strokes. Bikes like this 1996 XR400R were fun and reliable, but not really competitive with the best two-strokes of their day (even though many people tried to make them into MX racers). Ironically, it would be Yamaha, not Honda that would usher in the rebirth of the valve-and-cam motocross racer. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike Magazine |

While these Honda Cubs, Dreams and Scrambler 305’s were certainly excellent forms of reliable transportation, they lacked some of the excitement of the competition. The ultra-fast Kawasaki triples and versatile Yamaha Enduros both offered superior performance to anything in Honda’s lineup and they had nothing at all to compete with the motocross machines of Europe.

|

|

In 1997, Yamaha rocked the motocross world with the introduction of Japan’s first purpose built four-stroke motocross racer, the 1998 YZ400F. While Husqvarna, Husaberg, ATK and others had produced racing four-strokes prior to the YZF, none were as refined and appealing to the average consumer as Yamaha’s five-valve wonder. |

All that changed in 1973 with the introduction of Honda’s first performance two-stoke, the 1973 CR250M Elsinore. The Elsie was a clean sheet design and featured a light and powerful piston-port two-stroke single and off-road-ready suspension. The CR set new standards for motocross performance and signaled a major shift in strategy for Honda. Within in a few years, Honda would have both a 125 version of the CR available and a line of two-stroke enduros as well.

|

|

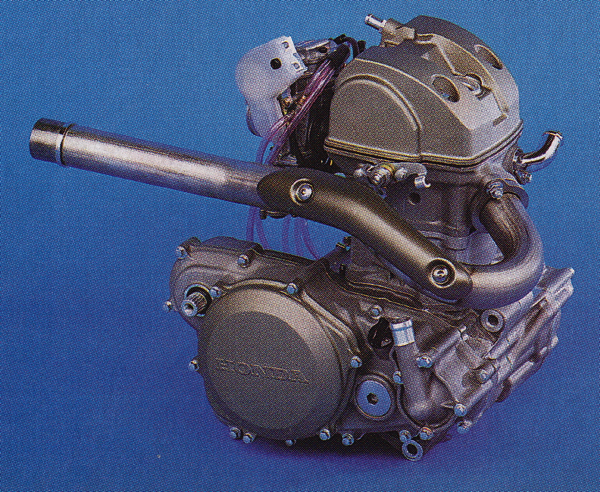

Unlike Yamaha, who had borrowed liberally from their road race department, Honda chose to go a completely new direction with their four-stroke power plant. The new motor would be a clean sheet design, taking inspiration from both modern and classic four-stroke thinking. |

While their two-strokes proved a massive success, Honda did not completely abandon their four-stroke business. The arrival of the XR’s in the late seventies gave off-road enthusiasts a four-stroke option for desert, enduro and play riding. While fun and nearly indestructible, the XR’s were heavier, less powerful and generally not as serious as the two-stroke competition. Even though many XR’s made it to the motocross track via conversion kits and elaborate modifications, the results were rarely satisfactory.

|

|

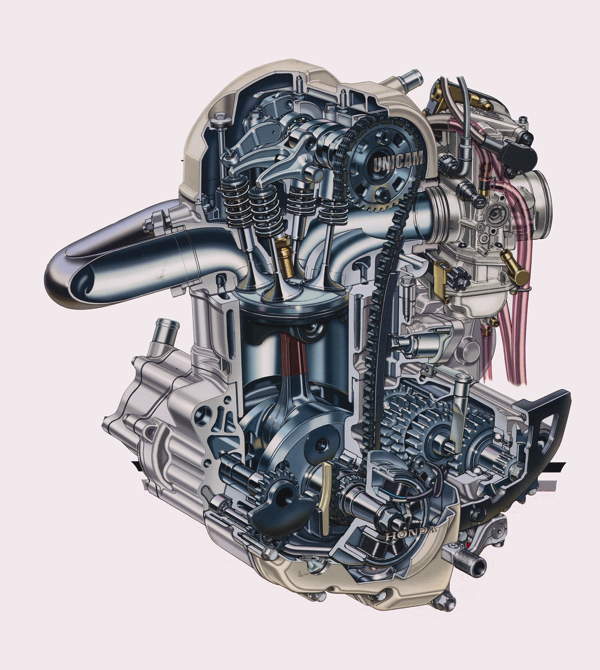

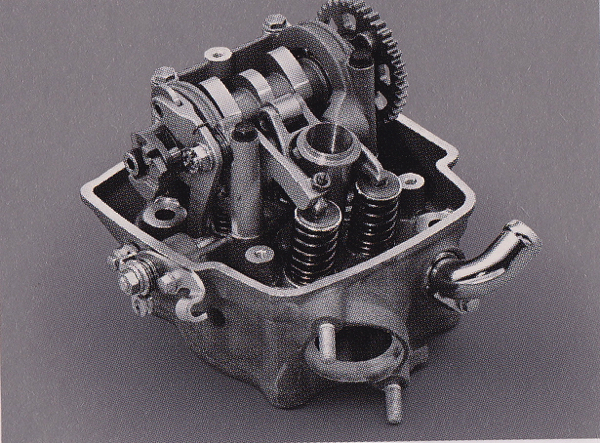

Probably the most interesting feature of the new CRF power plant was its unique “Unicam” valvetrain. By using a single cam to actuate its four-valves instead of the more traditional DOHC layout, the Honda engineers were able to shave a full pound off the motor and lower the center of gravity on the single heaviest part of the bike. |

In 1996, Honda made major waves in the off-road industry with the introduction of an all new 400cc four-stroke. Unfortunately, this new thumper was not a fire-breathing racer, but a reintroduction of their popular mid-size XR. The XR350R was considered by many to be Honda’s best off-road four-stroke during its short lifespan in the mid-eighties and the all-new XR400R was a worthy successor to that heritage. As before, it was not really racer, but that did not stop countless valve-and-cam enthusiasts from bolting on A-Loop tanks and booming exhausts in search of turning it into one. Bored-out and breathed-on XR’s, DR’s and KLX’s were all the rage in the mid-nineties and the hopped-up play bikes became a fairly common sight in the vet classes at many tracks around the nation.

|

|

Like the YZF, the new CRF used a Formula 1 inspired ultra-short skirt “slipper” piston to decrease friction and lower reciprocating mass. |

While the arrival of the new XR certainly generated plenty of interest in four-strokes in 1996, it was nothing compared to the bombshell Yamaha had in store for 1997. Early on in the ‘97 season, rumors began circulating that Yamaha was actually planning to race a works four-stroke in the AMA Nationals. While this initially met with more than a fair amount of skepticism, all that changed when Doug Henry rolled out the works YZM400F at the Supercross finale in 1997 and promptly waxed the field. Prior to this, a four-stroke had never even qualified for a 20-man main event, much less won one. A few months later, that shock would be compounded by the news that Yamaha would actually be bringing a production version of the YZM400F to market for the 1998 season.

|

|

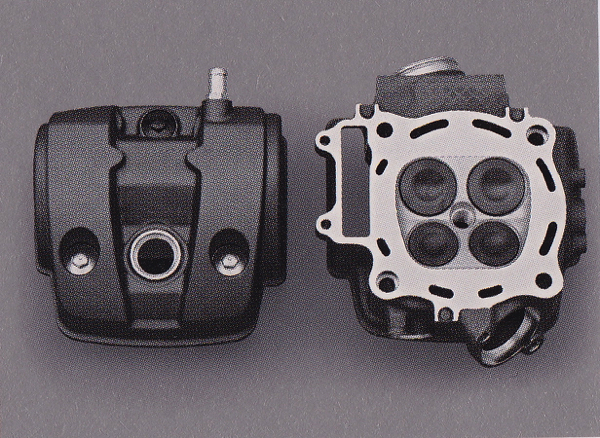

Unlike the five-valve YZF, the new Honda used a more traditional four-valve head layout. Titanium was used for the intake to reduce weight, while steel was employed for the exhaust for improved longevity. |

From the start, the new YZ400F was a tremendous success for Yamaha. The bike was lauded by the press and snapped up in droves by consumers. With the YZ400F, Yamaha had caught the other Japanese manufacturers napping and none of them even had a four-stroke racer on the drawing board. Both Husqvarna and Husaburg had four-stroke motocross machines in production, but neither was as refined or appealing to two-stroke customers as the YZF. They both offered a very old-school four-stroke flavor that was more akin to a hopped-up XR than a snappy two-stroke. For racers raised on the refinement and performance of the Japanese machines, the YZF was the only game in town.

|

|

Originally introduced on the 1997 CR250R, Honda’s first generation aluminum perimeter frame was certainly trick, but less than stellar on the track. By 2002, careful refinement had worked out most of the kinks in Honda’s alloy design. |

For Honda, the arrival of the YZ400F was a bit of a black eye to a company that had prided itself on four-stroke performance for five decades. Long the champion of four-cycles on everything from weed-eaters to road-racers, the red team had been bested at its own game. With the sting of the YZF fresh in their minds, Honda’s engineers set about making a better motocross mousetrap.

|

|

The new CRF power plant weighed in at 65 pounds and offered a smooth shifting five-speed transmission and excellent response. Honda had taken great pains to make the CRF as easy to transition to as possible, and that effort showed in its instantaneous throttle response and hassle free starting. Unlike the YZF, the CRF required no elaborate starting drill and it proved no harder to light than a well-jetted two-stroke. |

With the development of what would eventually become the CRF450R, Honda’s engineers had the benefit of looking at what worked and what didn’t on the original YZF. The Yamaha was certainly an amazing machine, but it was not perfect. The DOHC five-valve motor was powerful, but also easy to stall and difficult to relight in the heat of battle. The starting procedure was incredibly complicated compared to any two-stroke (or any kick-and-go XR for that matter) and accidently killing the motor often meant the end of your race. Compression braking was also a new experience for two-stroke aficionados, and the YZF really threw out the anchor when the throttle was chopped. Another annoyance was the nasty bog the YZF displayed if care was not taken with the throttle. If you whacked the throttle open suddenly (as one would do on any two-stroke), the YZF was likely to hesitate and throw you over the bars.

|

|

The arrival of the CRF450R was big news in 2002. Lighter, leaner and easier to ride than the Yamaha and KTM, the red rooster proved an instant hit with consumers. |

Weight was also an issue and the YZF was a big boy. At nearly 250 pounds, the bike was a good 20 pounds heavier than an YZ250 two-stroke and you felt every one of those lbs. The tall motor and heavy oil tank carried in the frame gave the bike a slightly top heavy feel that was noticeable on the ground and in motion. While front wheel traction was quite good, the overall bike was anything but nimble and once the YZF built up a head of steam, it was difficult to change its intended path.

|

|

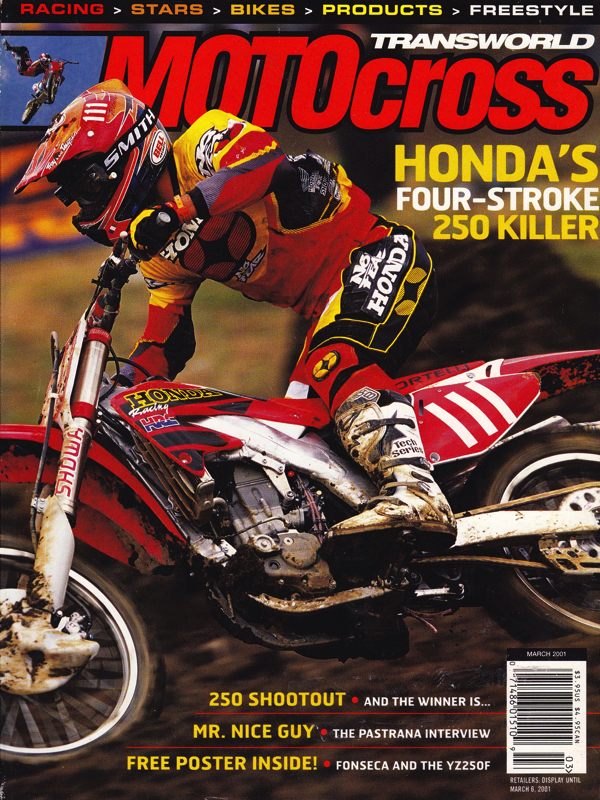

In October of 2000, Sébastien Tortelli debuted the works RC450 four-stoke for the first time at the last round of the All-Japanese Nationals. Ironically, Ernesto Fonseca would debut an even more groundbreaking four-stroke at the same race, Yamaha’s first YZ250F. Photo Credit: Transworld MX |

In developing the new CRF450R, Honda looked at all these issues and tried to address them. When Yamaha had developed the original YZ400F, they had borrowed heavily from their road race department, but Honda chose to go a different direction with the CRF. Instead of loping one cylinder off a CBR600, or hopping-up an existing XR motor, Honda went back to the drawing board for an all-new design. The new power plant would feature a Formula One inspired ultra-short-skirt piston for low mass and reduced friction and employ four-valves in the head (titanium for the intake, steel for the exhaust). For the valvetrain, Honda would eschew standard dual-overhead-cam layout common to high-performance four-strokes. Instead, they spec’d a unique single-overhead-cam design they dubbed “Unicam”.

|

|

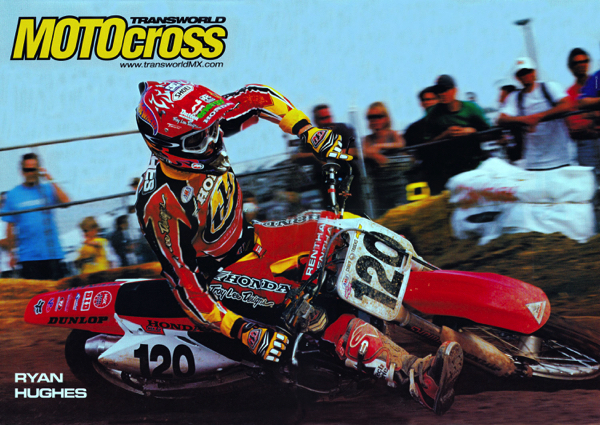

After the debut in Japan, a returning from abroad Ryan Hughes was picked to pilot Honda’s newest baby in the 2001 Motocross Nationals. Using the same one-year works bike exemption Yamaha employed in 1997, Honda was able to race a pre-production CRF450R throughout the summer. Both Hughes and Mike LaRocco would spend time shaking the new machine down prior to its 2002 production debut. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda/ Transworld MX |

The Unicam layout allowed for a more compact head that both saved weight (a full pound according to Honda) and lowered the center of gravity of the motor. To further lower mass, Honda decided to not use the separate oil tank employed on the Yamaha. Instead, the Honda carried all of its vital fluids in the motor itself, with the motor oil and transmission fluid enjoying separate sealed systems. The advantage of this design was that it prevented contamination from the clutch and transmission from getting into the rest of the motor. The downside, however, was its greatly reduced overall oil capacity.

|

|

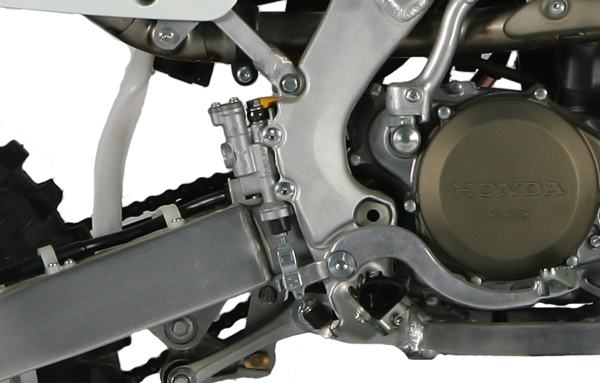

When designing the CRF, Honda looked to shave ounces from the bike in every way possible. One area that was targeted was oil capacity and new Honda carried much less of the precious fluid than the YZF. Unlike the Yamaha, the Honda did not use a remote oil tank and carried all its fluid in the motor itself. Also unlike the YZF, the CRF’s lubrication systems were segregated into separate chambers for the transmission and the motor proper. This meant that particulate contamination from the clutch and trans could not damage the rest of the motor, but it also meant careful care had to be paid to oil levels due to the reduced capacity. |

For the chassis, Honda decided to stick with an alloy perimeter design similar to the ones they had been using since 1997. Now on its third generation, this new chassis was smaller and more forgiving than the controversial first and second generation alloy designs. In the five years since the original aluminum CR, Honda had worked out where best to add and reduce material to provide the most strength, while not sacrificing comfort and durability.

|

|

The third generation alloy chassis on the new CRF was well received by most, with a light (for a four-stroke) feel and excellent ergonomics. Some riders complained of a push in the front end, but other did not notice any errant steering. Overall, it was not quite as precise in the turns as the Yamaha, but far lighter feeing on the ground and in motion. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer/ Dirt Rider |

|

|

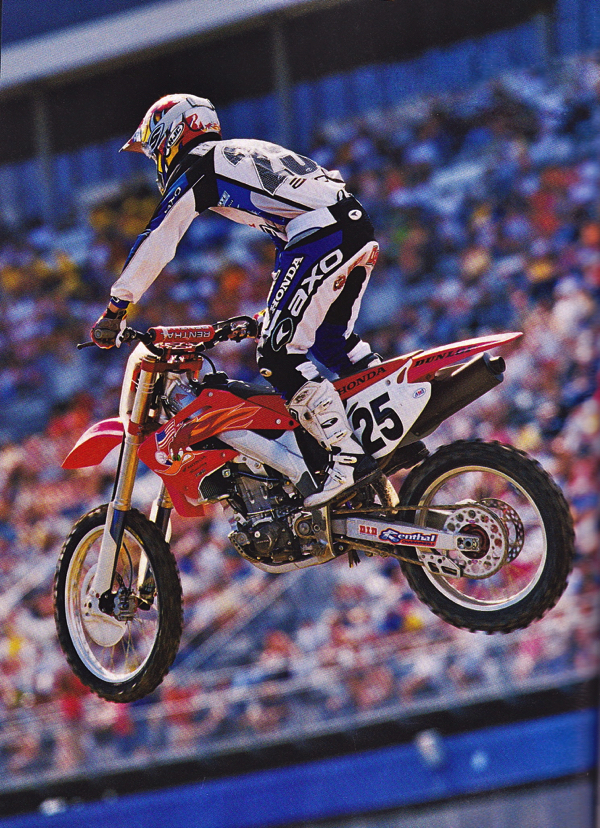

Fresh off taking Yamaha’s new YZ250F to second in the 2001 125 East Supercross standings, Nathan Ramsey was tapped to pilot the production version of the CRF450R in Supercross and Motocross for 2002. While Nathan would finish the Supercross series in sixth, he would give the new bike its first AMA victory with a surprising win at Pontiac in April. Photo Credit: Simon Cudby/RacerX |

Once the new CR450R hit the market in the fall of 2001, it became apparent Honda had a winning machine on its hands. The new CRF was a remarkable 15 pounds lighter than the Yamaha YZ426F (the YZF400 got a bump in displacement to 426cc in 2000) and required none of its annoying starting drill. There was no finding top-dead-center, pulling compression releases and hunting for buried hot-start buttons. On the new CRF, you just kicked it like any other motocross bike. As long as you gave it a good swift kick, it usually started in one or two stabs, hot or cold. If you did kill it in the heat of battle, the hot-start was placed right on the clutch perch, where you could easily find it.

|

|

The third generation of Honda’s alloy chassis was much narrower and more accommodating than earlier variations. Much of the vibration, harsh ride and numb feel were gone and the CRF proved one of the most comfortable machines of 2002. |

On the track, the CRF was no power house, but it was competitive. Power output was impressive, but the powerband was actually closer to Yamaha’s original YZ400F than the then current YZ426F. Where the YZ426F hit hard and pulled like a traditional Open bike, the CRF pumped out a more mellow flow of torque from its 449cc’s. The motor was very responsive and there was none of the hesitation or bog that had plagued the YZF since its introduction. Power was broad, but at no point was it awe inspiring. Overall, it was pleasant and easy to ride, but not as fast as the rocket-sled YZ426F or meaty KTM 520SX. This was actually not a bad thing on an Open bike and most riders found it easier to go fast on the smooth CRF than the arm-stretching Yamaha and KTM.

|

|

On the track, the new CRF motor proved more pleasant than awe-inspiring. Power was very good off idle, with very little hesitation. In the middle, the Honda did its best work and it produced a smooth flow of forward thrust. There was not a ton of top end to work with, but the bike could be revved out in a pinch. Overall, it was slower than the hard-hitting Yamaha and incredibly broad KTM, but easier to ride and certainly competitive. |

In designing the CRF450R, Honda had tried to make the bike as easy as possible for two-stroke converts to feel comfortable on. To that end, the engineers went out of their way to address the things that put off neophyte thumper pilots. Greatly reduced compression braking, trouble free carburation and no starting hassles made the switch to the CRF much less jarring than the transition to the YZF. It was still a four-stroke, but many of the things that made a racing thumper hard to live with were greatly lessened.

|

|

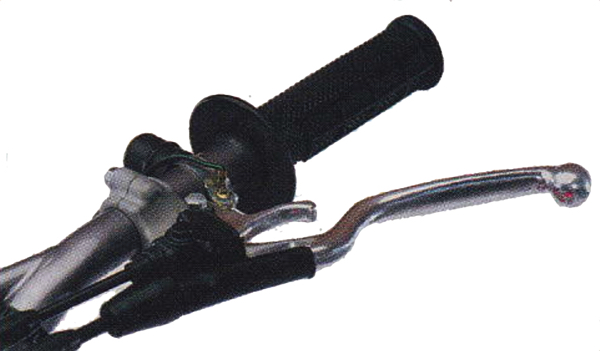

One aggravation with the Yamaha was the difficulty of getting it started in the heat of battle. By adding an automatic compression release and moving the “Hot Start” to the clutch lever, Honda was able to defuse much of the trepidation two-stroke pilots felt about moving to the often-finicky machines. |

While the motor on the Honda was a pleasant surprise, by far its most shocking virtue was its excellent suspension. By 2002, Honda had endured a full 14 years of being lambasted (with good reason) in the press for their miserable forks. Every year they promised improved performance, and every year they failed to deliver. Some years they came with KYB’s and some years they came with Showa, but one thing never changed; their sub-par performance.

|

|

Yes Virginia, Honda does indeed know how to produce a decent set of forks. For the first time since the heyday of big hair and parachute pants, a racing Honda actually had a decent set of silverware. These Showa forks were plush, well sorted and the best units seen on a red machine in fifteen long wrist-abusing years. |

Well, all that changed in 2002 with the introduction of the new CRF450R (and its all-new two-stroke stable mates). For the first time since 1987, a Honda motocrosser actually had a great set of forks. Offering 16 settings for compression and rebound, these Showa units took every track obstacle in stride. Hits that would have had the rider cringing in 2001 were absorbed without a snivel in 2002. They were plush, well controlled and proof Honda could actually produce a decent set of forks.

|

|

North American bound CRF’s got this big aluminum silencer with a large turned down stinger tip, while those tagged for Europe received an enclosed tip mandated by the FIM. Unfortunately, neither version proved particularly quiet and the new CRF turned out to be just as auditorily offensive as the booming YZF. |

Out back, the CRF once again featured Showa components and offered 17 selectable settings for low-speed compression and rebound, as well as 3 turns of adjustment on the high-speed compression. Much like the forks, shock performance excellent and the CRF offered a plush and well controlled ride. The overall chassis was very sensitive to ride height, however, so caution had to be paid to getting the sag correct. If you let the rear drop too low, then both the turning and suspension performance suffered.

|

|

Ramsey would finish tenth overall in the 2002 National Motocross series on the new CRF. His best finish would come at Red Bud in July, where he would card a hard fought second. |

As to turning, this was by far the most controversial part of the CRF package. Some publications (most notably MXA) claimed the CRF exhibited a push in the turns, while others found no fault with its turning manners (I personally purchased a CRF450R in ’02 and never had any issues with its handling). Compared to the razor sharp YZF, the CRF was certainly less precise, but it was far from horrible. After MXA began harping on the CRF’s handling, several companies came to the rescue with additional offsets to adjust the steering head angle. While there were many choices, few of them made any real difference. The biggest improvement would come a year later in 2003, when Honda would adjust the rear linkage to raise the rear of the bike and steepen the head angle. Overall, the CRF’s light feel and comfortable ergos made it an excellent place to do business. It was no RM125 in the corners, but for an Open bike, it was an able handler.

|

|

In another effort to save weight, Honda integrated the CRF’s rear brake reservoir and master cylinder into a combined unit. While certainly light and compact, some rider had problems with boiling its meager fluid capacity. |

|

|

MXA’s vociferous complaining about the CRF’s handling was well known in 2002 and many companies were happy to come to the CRF’s aid with a myriad of offset clamps to tighten up the wayward front end. Whether or not there was really a problem is certainly a matter of opinion, but Honda would take the criticism to heart and take steps in 2003 to improve the CRF’s turning prowess. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

As to the rest of the CRF, it was typical Honda, with excellent component quality and flawless fit and finish. It felt great new and stayed feeling that way longer than the other brands. The brakes were still considered excellent for the time, but a switch to a smaller integrated rear master cylinder (to save weight) caused some riders to boil over the rear binder. Some riders also had issues with the valves, but overall, the new power plant proved very reliable.

|

|

In 1998, Yamaha took the first steps toward a four-stroke future with their amazing YZ400F. Four years later, Honda made this future a reality with the introduction of a mega-thumper of their own. Lighter, less finicky and easier to ride that the YZF, the new CRF turned four-stroke sceptics the world over into true believers overnight. |

In 2002, Honda took the plunge back to their roots with an all-new four-stroke motocrosser. The CRF450R was innovative in design, lighter than the competition and more accommodating to thumper neophytes. It was a four-stroke designed to appeal two-stroke lovers and they snapped them up in droves. Within a year of the CRF’s release, race tracks across the country were awash in red four-strokes. It was certainly not perfect, but it was easy to ride and required less of a learning curve than the YZF. In 1998, Yamaha landed the first blow to two-stroke with their amazing YZ400F, but in 2002, the true coup de grâce was delivered by Honda and their CRF450R.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier