For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the 1978 Yamaha YZ400E.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the 1978 Yamaha YZ400E.

|

|

In 1978, the Yamaha YZ400E was one of only two Japanese entries into the Open class. Honda had yet to dip its toes in the big bore market and Kawasaki had run back to Japan with its tail between its legs after the tepid response the KX400 and KX450 had received. At the time, the Europeans were still delivering the best Open class performance available and the Japanese were still trying to sort out that magic big bike formula. |

In 1975, Yamaha introduced the masses to the joys of long travel suspension with the introduction of the limited production YZ250B and YZ360B. These two “works replicas” were light, exotic and out of the budget of most weekend warriors. Based on the designs of Belgian engineer Lucien Tilkens, the new YZ’s took the sport by storm with their works-like suspension and cutting edge performance. Offering twice the travel of conventional dual-shock arrangements of the time, the new monoshock suspension was a revolution.

|

|

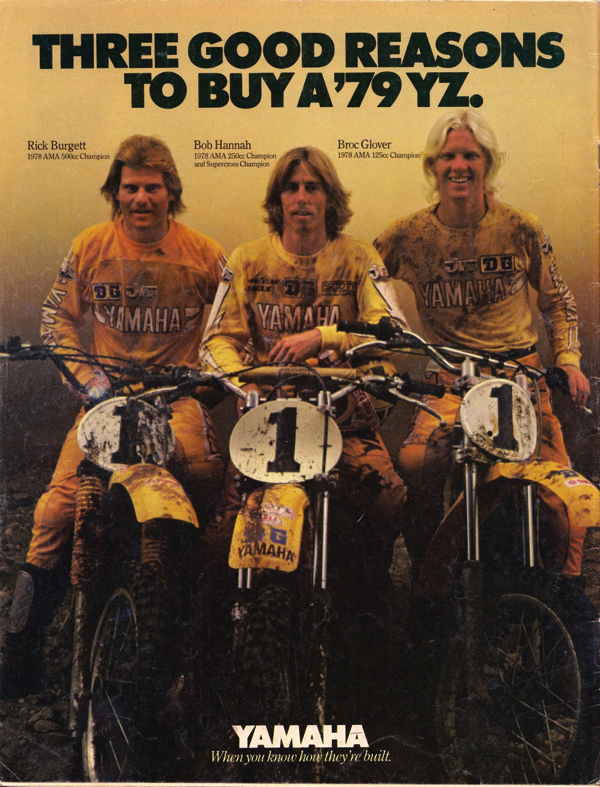

Super Team: The 1978 season turned out to be a banner year for Yamaha in the US. Team riders Rick Burgett, Bob Hannah and Broc Glover captured all four major AMA titles. Both Glover and Hannah would go on to capture more titles for the brand, but for the man they called the Lumberjack, the 1978 season would prove the highlight of his career. |

In 1976, Yamaha revamped their motocross lineup once again by incorporating the MX and YZ line into one machine. Previously, the YZ had been for pros only and the MX had been for the everyman racer. The new machine kept the YZ name, but not its exotic materials and sky-high price. With its air forks and Monocross suspension, the ‘76 YZ400C was still one of the most trick machines on the track, but its new personality was friendlier and less expert-oriented than its high-strung predecessor.

|

|

A new chromoly (or chrome-moly as it was known in 1978) steel frame for ’78 was both lighter and stronger than the mild steel unit used in 1977. While stronger, the quality of steel employed by the Japanese was still considered a grade below the incredibly tough high carbon steel found on high-end machines like Husqvarnas in 1978. |

Amazingly, by 1977, the Yamaha Monocross was already beginning to fall behind the best suspension designs of the time. Suzuki’s new RM line had leapfrogged the YZ’s in terms of travel and performance, while incurring none of the Mono’s weight and packaging issues. By moving the dual shock’s mounts forward, the Suzuki engineers were able to increase travel, while keeping weight down and allowing plenty of cooling air to reach the dampers. With the YZ, the placement of the shock deep in the center of the frame backbone meant both that a great deal of weight was carried high on the chassis and the damper would not receive very much cooling air.

|

|

In Yamaha’s original Monocross design, the YZ’s large DeCarbon single shock was carried inside a hollow channel in the frame’s main backbone. While this originally gave the Yamaha machines a significant travel advantage, it did lead to other issues. With its damper buried deep inside the chassis, fading was always an issue and the unique frame geometry of the monoshock design could make the bike unpredictable when not under a load. By 1978, The Monocross’ advantages had all but disappeared and new long-travel dual-shock systems from competitors like Suzuki were actually offering more travel and better performance. |

Predictably, this led to handling issues and these early monoshocks were known both for fading dampers and a nasty habit of kicking under deceleration. Under power, they worked reasonably well, but once the throttle was chopped, they tended to pitch forward and react unpredictably. This trait, known as “Yama-hop”, only worsened at the YZ’s shock got hot and the damping went away.

|

|

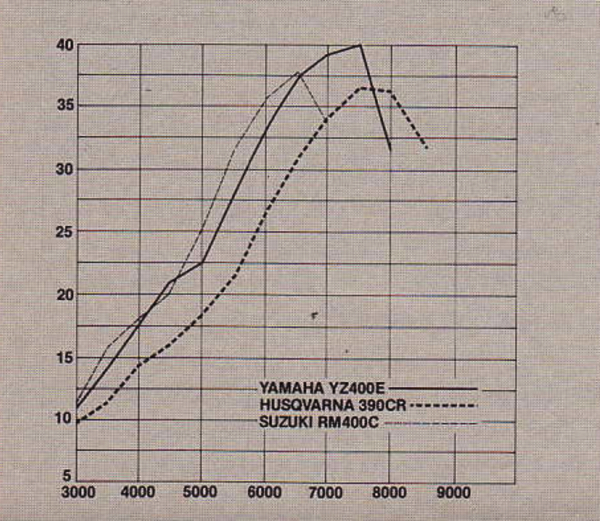

Hot Rod: In Open class racing, it was not the amount of raw power that made the Euro’s so dominant, but rather the quality of that power. This was a fact that seemed to flummox the Japanese during the seventies, as they continued to pump out one hard-hitting beast after another. The 1978 YZ400E was no exception. With its light flywheel and short-stroke design, the 397cc motor’s power was fast building and abrupt, with a hard hit and quick turn over. This made it more difficult to ride and more tiring than most of its class mates. In 1979, Yamaha would finally adopt a more Euro approach and spec an all-new long-stroke Open class engine that more closely mimicked the power of the Old World competition. |

In 1978, Yamaha professed they had finally nailed the culprit for this nasty behavior. According to them, the problem was flex in the frame and rear swingarm. In order to combat this, the engineers spec’d a new stronger frame and works-like boxed-section alloy swingarm for ‘78. The new alloy swingarm was both stronger and lighter than the steel unit it replaced, and the engineers promised an end to the rear end hopping and swapping that had become an unfortunate YZ trademark.

|

|

In 1977, Yamaha lured multi-time World Motocross champion Heikki Mikkola away from Husqvarna to race for the tuning-fork brand. Heikki would reward the brand with the ’77 500 World Motocross title. The new strong and light chromoly steel chassis and work-style alloy swingarm were the result of development done by the race team. |

For the frame, Yamaha decided to ditch the YZ-D model’s mild steel tubing and go with chromoly steel for the YZ-E. Short for “chromium-molybdenum steel”, chromoly was lighter and stronger than the low carbon steel common to most Japanese machines at the time. By switching to chromoly for the chassis, Yamaha was able to knock a full two pounds off the YZ400 for ’78. Unfortunately, even with the lighter frame and swingarm, the new D model still tipped the scales at an eye opening 242 pounds. This was portly even for an Open bike and the Y-Zed continued to be the heaviest bike in the class.

|

|

On paper, it was the YZ400E was the powerhouse of the class, but on the track, it was twice the work of the smooth, but deceptively fast Swede. |

|

|

In 1977, Yamaha dropped its one year dalliance with air forks (a relationship they have yet to rekindle) and switched back to a set of 38mm convectional Kayaba spring forks. For 1978, they added 20mm of fork overlap to the ’77 units and called it a day. Punching out a total of 9.8 inches of travel, these KYB units were considered the best forks in the class, offering a plush feel and excellent control. |

While the frame and swingarm were new for 1978, the rest of the YZ400E was largely a carryover from the ’77 D model. The motor was the same 397cc, 85mm x 70mm ground-pounder it had been in 1977. Fed by a 38mm round-slide Mikuni carb and six-peddle reed-valve, the ’78 YZ400 produced one of the most exciting powerbands on the track. Acceleration was explosive off the bottom, with a burly midrange and hard hit. Once past the midrange, power tapered off appreciably, but from corner to corner it was brutally fast.

|

|

Gyro Gearloose approved: The advent of long travel suspension brought with it several engineering issues to be overcome. One of the more challenging of which was how to handle the extreme fluctuations in chain tension as the suspension moved through the stroke. In order to keep the chain from derailing, Yamaha used a spring loaded tensioner to take up the slack and two big chain rollers to keep it all on track. Even with the rollers, failures were common and the YZ was notorious for snapping the upper roller and letting the chain chew through the air boot. Eventually, the engineers figured out the answer to this conundrum was not to add more complicated tensioners, but instead to move the countershaft closer to the swingarm pivot. |

On the track, the YZ offered one of the most thrilling rides of 1978. Because of its light flywheel and sudden delivery, the YZ was prone to wheelies and care had to be taken not to send the front fender skyward out of tight turns. It was snappy and quick revving, but more work than the smooth and mellow Husqvarna 390CR and Suzuki RM400C. In addition to its potent delivery, the YZ’s stubborn transmission often made life difficult. It was notchy and prone to missed shifts if care was not taken to catch the next cog. Power shifting was completely out of the question and the big yellow 400 demanded the clutch when shifting. Of course, this was no easy task with the Yamaha’s hand-cramping clutch pull and many savvy YZ pilots resorted to lengthening the actuator arm and swapping the stock clutch lever for a XT500 part to reduce the effort.

|

|

While certainly attractive, the stock Yamaha graphics were not long for this world. Plastic tanks were the bane of stock decals and that situation did not much improve until the advent of radiator shrouds in the early eighties. Even perforated aftermarket ones like these do not stand up for long against gas fumes. |

|

|

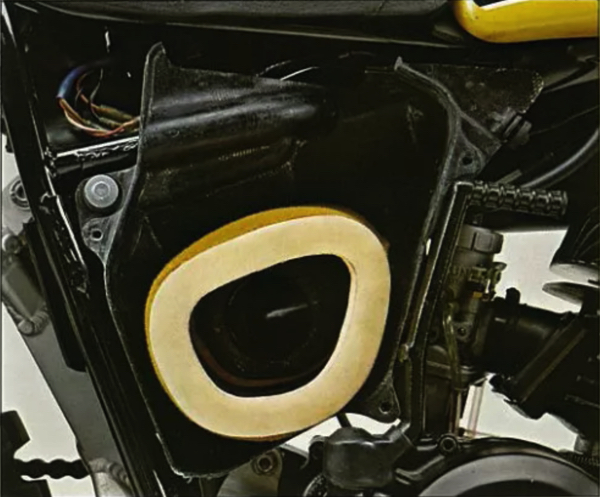

Fail: Probably the most problematic part on the YZ400E was its pathetic excuse for an air filtration system. The airbox itself leaked and required copious use of grease on every sealing surface to have any hope of a decent seal. In addition to the airbox’s porous nature, the filter itself was absolutely useless and would literally fall apart after the third washing. |

In the suspension department, the ’78 YZ400E was once again largely a carryover from ’77. Pumping out 9.8 inches of travel front and rear, the new bike did receive a minor upgrade with the addition of 20mm of slider overlap in the 38mm air/oil adjustable Kayaba forks. This was done to increase rigidity by offering more surface area and smoother action when the forks were topped out. Out back, the YZ-E continued to use a single large DeCarbon shock mounted down the centerline of the chassis. While lacking the trick remote reservoir of the Factory OW racers, the unit did offer an impressive 13 adjustable settings for compression and rebound.

|

|

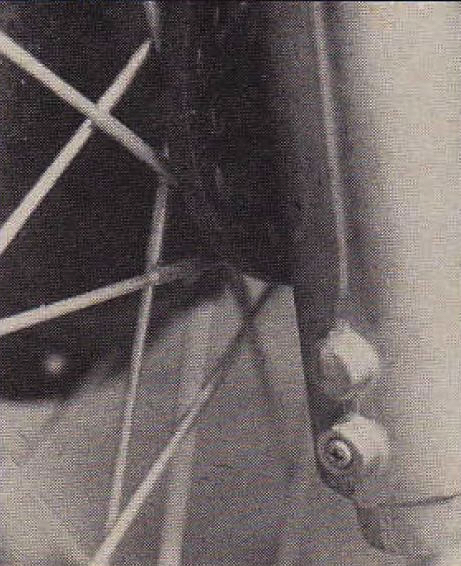

Seeing double: One odd side effect of adding 20mm to the forks internals was this weird dual nipple at the bottom of each leg. Instead of casting all new sliders, Yamaha reused the ’77 components and just added a second bleeder screw below the first. |

While most testers could not feel the benefit of the additional 20mm of fork overlap, the Yamaha’s Kayaba units remained some of the best components on the track. They offered no external damping adjustability, but the ride could be fine tuned by adding or subtracting air from the forks. Most riders preferred around 12 PSI in both legs and with those settings the KYB’s provided a plush and well-controlled ride.

|

|

Yama-hopper: A new longer and stronger alloy swingarm for 1978 improved performance of Yamaha’s unique Monocross suspension. While the swingarm reduced flex, the actual damper itself remained a mixed bag of performance. Under power, it reacted well and absorbed most hits without a whimper, but in throttle-off situations it could be violent and unpredictable. While the damping could be adjusted via a screw on the shock body (a very novel concept in 1978), the rebound remained very quick and the bike was prone to kicking on sharp hits and under braking. |

Out back, the new Monocross rear offered slightly improved, but not groundbreaking performance. The new alloy swingarm reduced flex and new more slippery bushings reduced friction, but the performance of its single damper continued to be flawed. Fading was still an issue due to its placement away from any cooling air. Without a way to sufficiently dissipate heat, the shock’s performance deteriorated rapidly after 15 minutes of hard use. When fresh, it worked most efficiently under power and test riders found that keeping their weight well back in the rough yielded the best results. While decent at taking hard hits, it could be slightly harsh on small chop and the bike continued to kick unexpectedly on rebound. Apparently, the dreaded “Yama-swap” was indeed not completely exorcised after all.

|

|

The stock silencer on the YZ400E was steel, non-serviceable and loud as hell. While suitably obnoxious, it was not any worse than the larger, but no less cacophonous unit found on the Suzuki RM400. |

Aside from an unexpected case of the hops, the YZ400E was a decent handling motorcycle. The short wheelbase that made it wheelie-prone yielded good turning manners and the Y-Zed proved the most nimble of the 1978 Open class machines. Both the RM400C and 390CR Husky were far more stable at speed, but neither could cut under the Yamaha in the turns. Ergonomics were very good (for the time) and riders found it easy to move around on the big Yammer. Several riders commented on the YZ’s comfortable seat and the middle of the bike was much slimmer than the competition due to its lack of dual shocks.

|

|

While not particularly easy to ride, there was no denying than the YZ400E made major power. Here Rocket Rex Staten (6) and Rick Burgett (14) power their Yamaha’s to the front of the 1978 St. Petersburg 500 National. Photo credit: Dick Miller Archives |

|

|

While many faster riders appreciated the YZ’s lighting-fast response and prodigious hit, none could be found in favor of its cranky gearbox. Power shifting was completely out of the question and the big Yammer demanded you back off throttle and feed in some clutch to catch the next cog. |

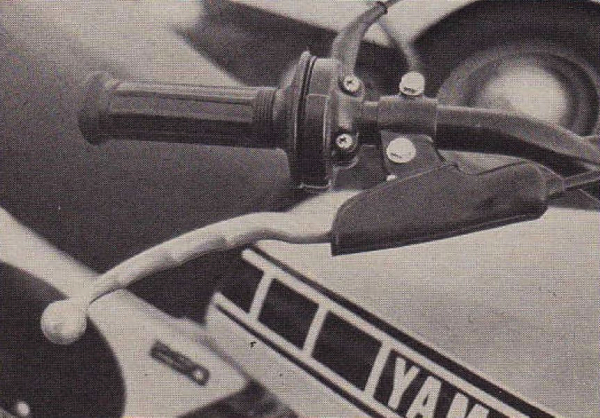

In the details department, the YZ was pretty typical for the era, with several nice touches and a few glaring missteps. Braking front and rear was considered quite good, but care had to be taken not to allow the rear to get out of adjustment. If not set up properly, the pedal would bottom out on the frame and render it nearly useless at an inopportune moment. On the plus side, both the stock clutch and brake levers featured zoot capri indentations that were designed to fit your fingers. Very trick and comfortable.

|

|

As Mike “Too Tall” Bell demonstrates, the ’78 YZ400E could be an able handler in the turns. Where is got a little spooky was at speed, where the YZ’s short wheelbase and bucking shock made life unnecessarily interesting. |

|

|

In 1978, all the full size YZ’s got these very trick indented levers designed to fit your individual fingers. |

Due to the design of the engine, the countershaft was several inches from the swingarm pivot and this led to issues with the chain rollers. At full extension, the top roller was put under a great deal of strain and broken rollers were common. Worst of all, when the roller expired, the chain liked to chew directly into the intake boot, allowing a direct shot of terra firma into the top end, ugh. Of course, the YZ’s airbox did not need a lot of help in this department, as the stock filter was pretty much worthless. When new, it sealed poorly and after a few cleanings, it was guaranteed to come apart in your hands. JT Racing sold a lot of Phase 2 Filters in 1978.

|

|

In 1978, YZ’s outside the USA were actually white and red, instead of our accustomed bumblebee yellow and black. In 1985, Yamaha USA would adopt the international colors, before going pink in the early nineties. |

|

|

The 1978 YZ400E continued a Yamaha tradition of powerful, but demanding Open class entries. It was plenty fast, but hard to ride and even harder to shift. It had great forks, but a shock hell bent on dislodging its pilot. If you were fast and aggressive, it could be made to work, but for average Joe’s there were better alternatives. |

Overall, the 1978 Yamaha YZ400E was a solid Open class offering. It could have used a longer swingarm, and a remote reservoir for the shock would have been nice, but it was capable of winning races in stock form. It was plenty fast and offered an excellent set of front forks, but its sudden delivery and slightly wayward handling made it harder to manage than the best from Europe. If you liked your big bore with a decidedly Nipponese flavor, it was a good choice, but if absolute performance was your top priority, there were better Old World alternatives available.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier