|

| In 1989, Suzuki shed years of stodgy styling with the all-new RM250. Cutting-edge in both design and style, the new RM was more modern, but not necessarily better, than the bike it replaced. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

The 1980s were a time of rapid change in motocross. The rise of Supercross led to changes in track design all across the country and massive technological gains made by the manufacturers meant bikes were all-but obsolete only a few years after their release. Show up at a race in 1988, on a bike from 1982, and you were likely to be laughed all the way back to the pits. In eighties moto, things moved at a quasar pace and if you blinked, the motocross world blew right on past.

|

| The zenith of early Suzuki 250 performance took place in 1982, with the amazing RM250Z. Faster stock than the other brand’s works bikes, the RM-Z laid waste to the competition and set a high-water mark for performance that Suzuki would not match for over two decades. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike magazine |

In the mid-eighties, that is just what happened to Suzuki. The darling of late-seventies moto, Suzuki had started off the decade with great bikes and tons of momentum. Supercross titles, shootout victories and consumer affection were all going Suzuki’s way in 1981. The yellow bikes dominated in the stadiums and on local tracks everywhere. With technology like their ground-breaking Full Floater rear suspension, light weights and rocket-fast motors, the RM125X and RM250X were the darlings of the industry.

|

|

In 1988, Suzuki came close to recapturing the 1982 magic with a redesigned and much-improved RM250. Excellent suspension and a strong motor highlighted the best RM250 in six years. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In 1982, Suzuki served up another beating to the industry with an even better RM250. The new liquid-cooled and Full Floater-equipped RM250Z was faster stock than most works bikes and wiped the floor with the 250 competition. In 1983, Suzuki made a major misstep by detuning their deuce-and-a-half thoroughbred. The new D model was pleasant and smooth, but unfortunately, a pale shadow of its knobby-shredding predecessor.

|

|

New bodywork offered a much slimmer and smoother profile for 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

The ’84 and ’85 seasons would bring new RM250s, but none of the old (yellow) magic. The Full Floater continued to dominate the suspension wars, but the horsepower of ’82 was nowhere to be seen. New bodywork and a coat of blue paint updated the looks, but all of that was just window dressing on a bike sorely in need of a new motor design.

|

|

A switch to case-reed for the ’89 promised quicker throttle response and more top-end power, but delivered neither. On the track, the new RM provided a hard hit and quick burst, but little else. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In 1986, Suzuki took a major gamble by shelving their original Full Floater suspension in favor of a more compact (and cheaper to produce) bottom-link design. The new suspension featured a unique eccentric cam linkage instead of the more traditional bell crank arrangement. Although much more compact, the new design proved prone to terrible amounts of stiction and ended Suzuki’s decade-long run of great suspension.

|

|

One of the major changes on the RM250 for 1989 was the switch to Kayaba’s new 41mm inverted cartridge fork. Seen on works bikes for half a decade, the USD design promised less flex under a load and improved ground clearance in the ruts. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In addition to the new suspension, Suzuki dialed up an all-new motor for 1986 and it proved just as disappointing as the new-look Full Floater had been. Incorporating a variable exhaust device for the first time, the new blue motor looked modern, but ran very old fashioned. Compared to the omnipotent CR250R, the new RM was slower, worse handling, less reliable and downright ugly.

|

|

After offering cobby looks and poorly-fitting bodywork for half a decade, the transformation the RM250 made in 1989 was downright startling. The new bike was slim, trim and as beautiful as anything available at the time. About the only beef riders had with the new layout was its low seat and rather compact pilot compartment. Shorter riders had no issue, but those over 5”10” found the new machine somewhat cramped. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

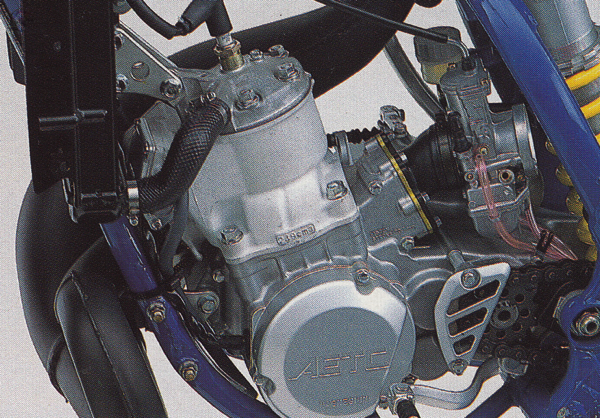

In 1987, Suzuki finally started to get things turned around with another virtually all-new, and this time, much-improved RM250. The new bike ditched the unsuccessful eccentric-cam Floater of ’86 in favor of a much better-working and more conventional design. The ’86 slug of a motor was also ash-canned and replaced with another all-new design. The new engine retired the Automatic Exhaust Control (AEC) resonance chamber of ’86 and replaced it with a more advanced variable exhaust port device they christened Automatic Exhaust Timing Control (AETC). The new engine maintained the bright blue paint of the old mill, but offered much more competitive performance. Of all these upgrades, maybe the most significant was the switch to Kayaba’s all-new 43mm cartridge forks. With the arrival of these works-like units, the RM pulled par with the class-leading CR and leapfrogged over the damper-rod-equipped YZ and KX. In truth, about the only thing that was not better on the RM for 1987 was the styling, which continued to look stuck in 1982.

|

|

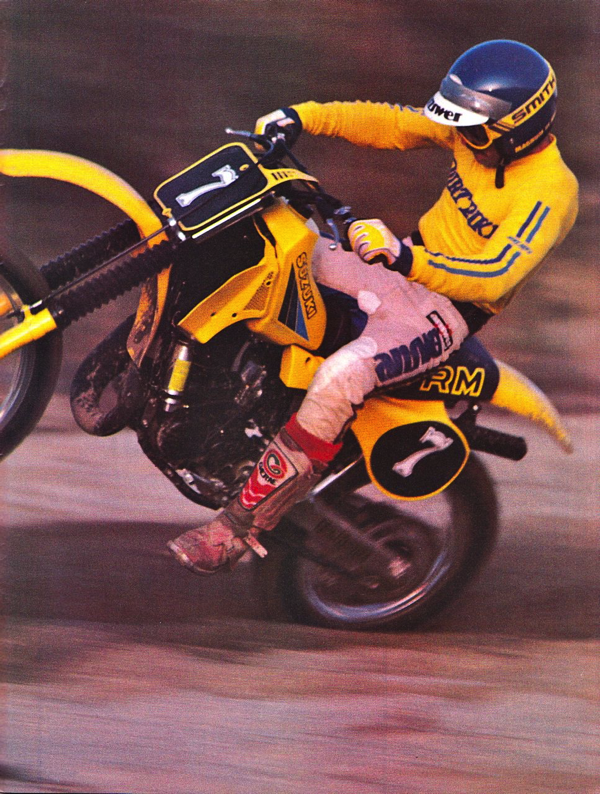

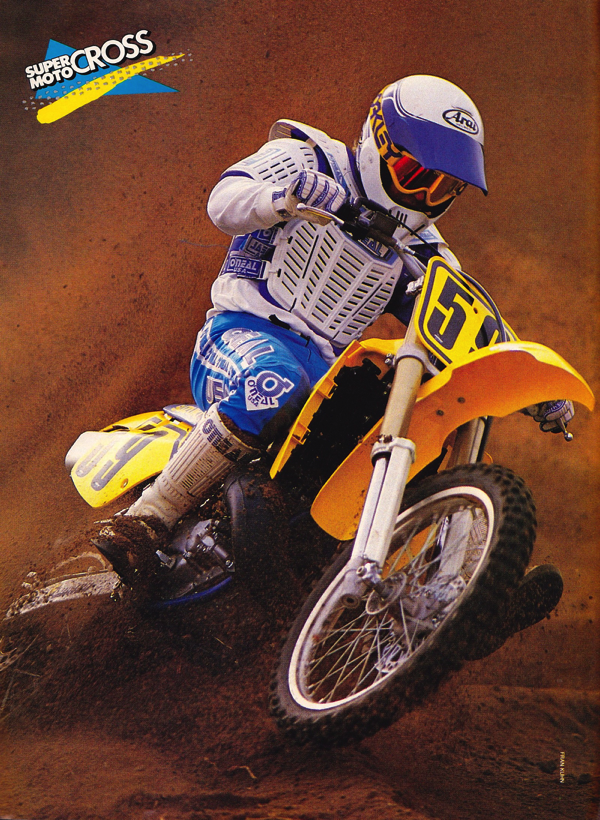

In 1987, Johnny O’Mara made the move to Suzuki after budget cuts at Honda left him looking for a ride. What followed were two injury-plagued years on sub-par bikes that he clearly did not like. In 1989, Suzuki finally delivered an RM250 that meshed with the former champ and we got a glimpse of the speed that took him to the 1984 Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action magazine |

The 1988 season brought with it a refinement of the 1987 RM250 package, but that refinement added up to the most competitive Suzuki in half a decade. The new bike still looked rather outdated, with its funky fenders and uniquely-suzuki styling, but under that moldy exterior beat the heart of a true thoroughbred. The 246cc AETC motor provided strong power and a potent midrange blast. The suspension gobbled up terrain and swallowed bumps that jarred riders on lesser machines. Handling was not perfect and the bike was prone to the occasional unintended shift (too little tension on the shift detent spring), but overall it was the best all-around package of 1988.

|

|

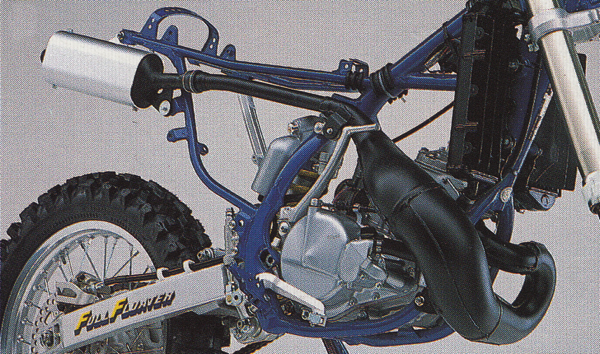

Underpinning the all-new RM250 was a redesigned chromoly steel frame that was lighter, stronger and slimmer than 1988. Favoring turning prowess over stability, the ’89 RM started a handling trend for Suzuki that has persisted to this day. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

This brings us to 1989, and the biggest redesign of the RM250 since the switch to a single shock in 1981. For 1989, literally not a single part was carried over from 1988. All-new bodywork highlighted the package and transformed the RM from an ugly duckling to one of the loveliest bikes on the track. Gone was the duckbilled platypus front fender (hooray!) and ill-fitting bodywork, to be replaced with sleek lines and slim ergos. The new bike maintained the yellow and blue theme Suzuki had used since 1983, but ditched the blue motor (personally, I loved the blue motors) in favor of a more understated silver motif.

|

|

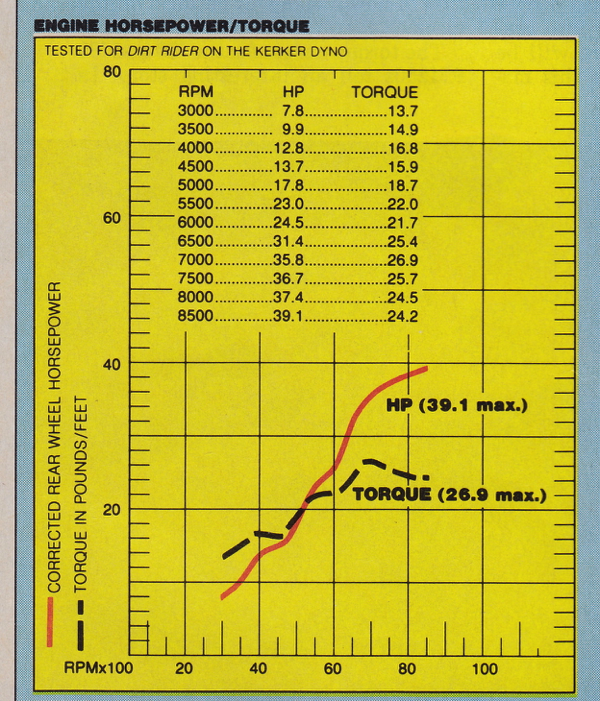

On the dyno, the new RM250 offered less horsepower than 1988, but slightly more torque. In the real world of dirt and berms, the new motor was potent, but far harder to ride than the year before. A light flywheel and an absence of low-end torque made it less novice-friendly, while a dearth of top-end overrun made pros less than enthusiastic. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider magazine |

The motor itself was an all-new design that maintained the AETC-style power valve of 1988, but bolted it to a totally redesigned top and bottom end. Lighter and more compact, the new mill dropped the cylinder-reed configuration of ’87-’88 and adopted a case-reed design more commonly seen on 80s and 125s. By moving the intake to the cases, Suzuki claimed to be able to charge the cylinder quicker and provide even faster throttle response and improved top-end power. Feeding that new intake was a 15% larger airbox and all-new 38mm Mikuni “Slingshot” carburetor. According to Suzuki, the Slingshot used a unique slide that combined the best traits of a round-slide (better sealing and low turbulence) and flat-slide (quicker response) into one design.

|

|

Even though it was an all-new design, Suzuki chose to not equip the RM with a fully removable rear subframe. Instead, the bike made do with a removable bar on the left side to aid shock service. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

Internally, the new motor maintained the piston diameter of 1988 (67mm) but increased the stroke slightly (70.8mm compared to 70mm the year before) to bump total displacement up to 249cc. Ignition duties continued to be handled by Suzuki’s PEI electronic ignition and on the exhaust side, an all-new “low-boy” pipe sat a full 3.9 inches lower on the chassis for 1989. In the bottom end, a new five-speed transmission featured revised ratios to match the motor’s new power characteristics and larger shift shaft for improved shifting performance.

|

|

The transmission on the RM250 was actually too easy to shift. Nearly any nudge of the shifter (intentional or not) was enough to knock the bike out of gear and false neutrals were a constant concern when riding. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

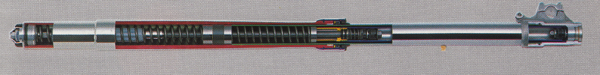

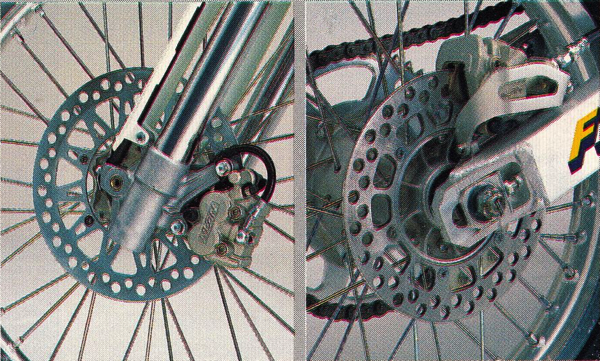

On the chassis front, the new RM featured a totally redesigned frame and radically altered suspension. The new frame was formed from tough chromoly steel and featured increased rigidity and a thinner profile for ’89. Up front, the biggest change for ’89 was definitely the addition of Kayaba’s new 41mm inverted cartridge fork. Seen on works bikes for several years, the inverted design offered increased rigidity and less overhang below the axle compared to a conventional fork design. Out back, the new RM maintained the bottom-link Full Floater design of 1988, but updated it with new ratios, a new shock and a beefier swingarm.

|

|

Under the correct conditions, the RM could be a potent motocross weapon, but its narrow power, twitchy handling and unbalanced suspension made going fast harder than on the red, green and white competition. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn |

On the track, the RM250 was a completely different machine for 1989. The bike was lighter by nearly four pounds and featured a much lower center of gravity. The lowered pipe allowed Suzuki to drop the tank 2.8 inches and the new seat and tank allowed much easier movement fore and aft. It felt easily ten pounds lighter than before and carved around the track like a powerful 125. Turning was light and accurate and the RM could carve a tight line around any bend. At speed, however, it was an absolute handful and pinning it on a fifth-gear straight took strength and a good deal of resolve.

|

|

The 249cc case-reed mill on the ’89 RM250 offered a hard hit in the midrange, but little usable thrust at the extremes. Both low-end and top-end power were unimpressive and the bike had to be kept within its narrow window of thrust to be truly effective. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

On the motor front, the new RM proved to actually be a step backwards from ‘88. The old motor, while no powerhouse, was snappy, broad, and easy to ride. With the new power plant, Suzuki went for hit, at the expense of usability. Off the line, the new RM offered a light-flywheeled and zippy feel very reminiscent of a big 125. There was not a lot of torque down low and the bike demanded a little clutch to pull past this lull into the meat of the power. Once in the midrange, the RM leapt forward with authority and pulled hard for a short duration, before petering out on top end. There was very little usable power above or below this midrange blast and the bike demanded a lot of shifts-per-lap to keep up a competitive pace. Compared to the long-pulling CR250R and burly KX250, the RM was both slower overall and far harder to ride. Once on the pipe, it could keep the green and red machines in sight, but you would need to execute two shifts for every one on the KX or CR.

|

|

While not as ultra-plush as the 46mm conventional forks found on the ’89 KX250 (or the 43mm conventional forks on the ’88 RM250 for that matter), the new 41mm KYB inverted forks on the RM250 delivered very good performance. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

|

|

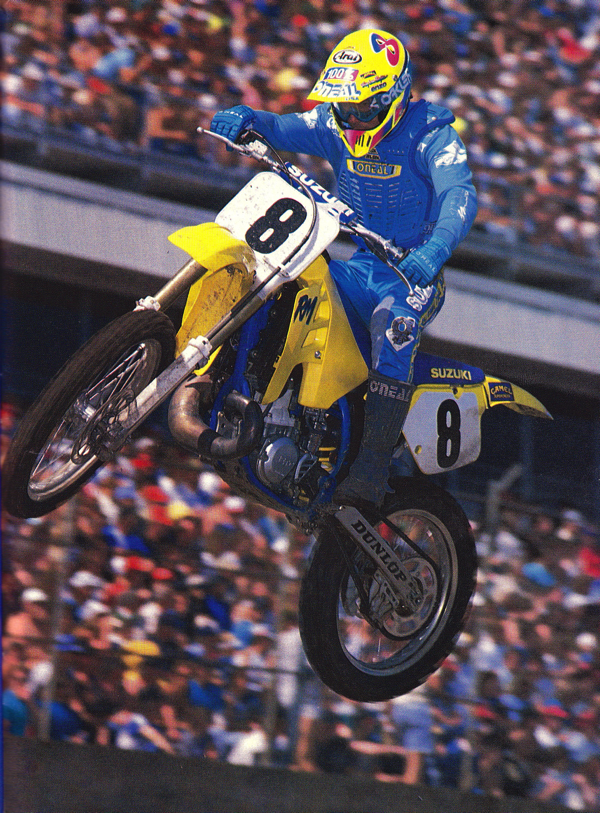

While the new RM250 was considered an upgrade for disciplines like Supercross, it did not necessarily improve the results for all of Team Suzuki’s riders. Erik Kehoe enjoyed his best finish of the year at round one, carding a 4th in the 250 main, before rounding out the series in 10th, three positions worse than in 1988. Photo Credit: Motocross Action magazine |

Much like the motor and chassis, the new suspension proved to be a mixed bag. The new 41mm inverted forks offered 12.2 inches of travel and 20 adjustable settings for compression and rebound damping. In terms of performance, they were far better than the abysmal 45mm Showa inverted forks offered on the 1989 CR250R, but not as plush as the excellent 46mm KYB conventional units found on the KX250. Once broken in, they offered good compliance and excellent control. The rigidity of the inverted design provided more feedback than the conventional units found on the KX, but fast guys appreciated the reduced flex and lowered propensity to get caught in deep ruts.

|

|

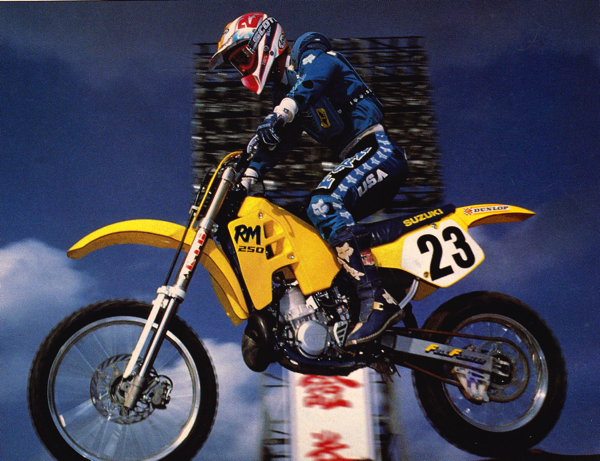

In 1989, Palm Harbor, Florida’s Ronnie Tichenor was Suzuki’s up-and-coming star. Indoors, he would take the new RM to a 7th overall, while outdoors he would fare better, powering his Suzuki to 4th overall in the final standings. Photo Credit: Fox Racing |

|

|

Not your father’s Full Floater: The rear suspension on the 1989 RM250 shared its name with Suzuki’s original and ground-breaking single shock suspension, but none of its actual design. While good at charging, its choppy performance on small impacts left it a notch below the KX250 in 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

Out back, the RM maintained the Full Floater name of yore, but shared absolutely nothing in common with the original design. For 1989, an all-new KYB shock offered 12.7 inches of travel and adjustments for both compression and rebound. This new unit featured revised bearings and bushings to reduce friction and a larger reservoir to improve cooling. On the track, the shock was decent at taking big hits, but slightly choppy in the rough. Because the front forks offered a lot of preload, the rear shock also felt slightly unbalanced. With stock springs and settings, the RM felt high in the front and low in the rear. Once dialed in, the suspension was raceable and far better than the grim Honda, but not as plush overall as the excellent Kawasaki KX250.

|

|

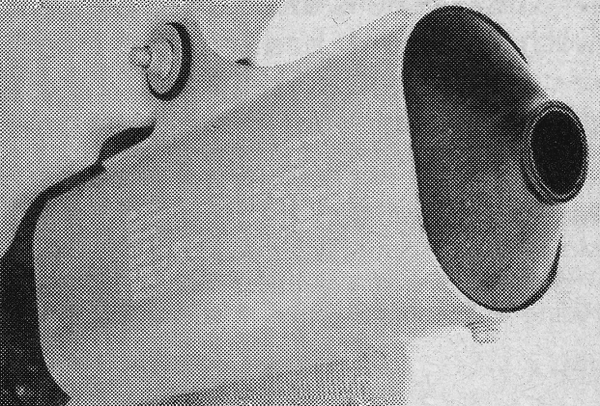

A new “low boy” pipe for 1989 lowered the RM’s center of gravity by relocating the pipe 2.9 inches lower on the frame. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

|

|

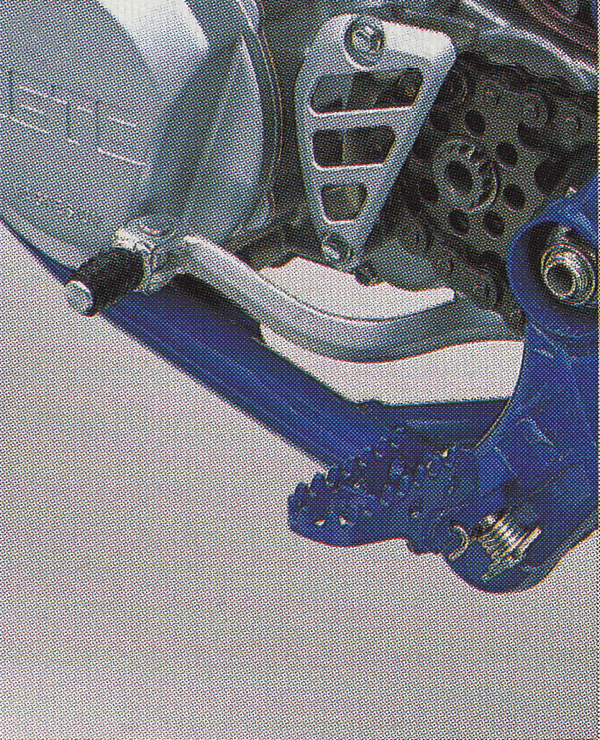

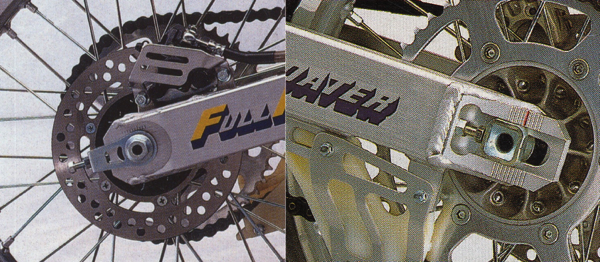

lots of little touches on the ’89 RM finally brought it up to speed with its competition. Items like this slotted chain tensioner (right) were far more modern and easy to work with than the cobby seventies-era units found on the 1988 RM (left). Photo Credit: Suzuki |

In the details department, the new RM made several steps forward and a few steps back. The new bodywork looked amazing and fit far better than before, but Suzuki continued to use a maddening assortment of bolts, screws and washers to attach everything. There were far too many oddball sizes and easily-stripped Phillips screws to contend with and the general quality of the fasteners was several steps below those found on a Honda. The new layout, while sleek and attractive, was far more cramped than 1988 and taller riders could find it difficult to extricate themselves from the RMs compact rider compartment.

|

|

A larger front rotor and redesigned calipers improved braking for 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

|

|

The 250 class of 1989 was a diverse lot with many strengths and several weaknesses. At the extremes you had the Kawasaki with the best suspension (but a bulky feel), and the Honda with the best motor (but suspension from the Marquis de Sade collection). Somewhere in the middle were the KTM, Suzuki and Yamaha, which were good at many things, but not a standout in any one category. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike magazine |

|

|

The silencer on the 1989 Suzuki RM250 could have rivaled anything you might see on a four-stroke today. Roughly the size of a Mack truck, this rebuildable alloy unit was replaced in short order by anyone looking to shave a few ounces off their new steed. |

New larger rotors improved braking but shifting continued to be problematic. Unlike the YZ, which was notchy and stubborn, the new RM was actually too easy to shift. Merely brushing against the lever was often enough to knock the transmission into a false neutral, with predictably dire results. On the reliability front, the new motor also proved to be a big disappointment. Piston and ring life was particularly poor and the RM liked to expire prematurely when pushed hard in deep sand or mud. The new airbox was also an issue and care had to be taken to prevent potentially disastrous air leaks.

|

|

At the Supercross season opener in Anaheim, Suzuki’s Johnny O’Mara looked to be on his way to taking the new RM to victory in its first outing. Unfortunately for O’Mara and Suzuki, however, this fairy tale ending was cut short when Johnny landed hard off a triple and snapped the steering stem on his works RM, handing the victory to his old teammate Ricky Johnson. Photo Credit: Motocross Action magazine |

|

|

In 1989, Suzuki threw out the baby with the bathwater and introduced an all-new type of RM250. Sharp, sleek and Supercross focused, this new type of RM favored turning prowess over all else and laid the tracks for nearly three decades of yellow shredders. While far from perfect, the new RM shed years of old-school engineering in favor of a modern and forward-thinking design. For Suzuki fans, the handling legacy we know today starts right here. Photo Credit: Suzuki |

Overall, the 1989 RM250 was a massive improvement in curb appeal, but not much of an upgrade on the track. Lighter, sleeker and lovelier than ever before, it was not up to recapturing the glory of a decade before. With its hard hit, sharp turning, and compact ergos, it made a great Supercross machine, but a less-than-stellar outdoor choice. High-speeds and choppy terrain exposed its narrow power and frenetic handling. Beautiful, but flawed, the 1989 Suzuki RM250 was a bike bred for Supercross, at the expense of everything else.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com