For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki and Suzuki’s first four-stroke motocross offerings, the 2004 KX250F and RM-Z250.

In 2004, Kawasaki and Suzuki introduced their first high-performance four-strokes aimed at the motocross market. Developed jointly by both manufactures and produced by Kawasaki, the new KX250F and RM-Z250 proved to be innovative, but flawed products. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The turn of the new millennium was a time of major transition in motocross. In 1998, Yamaha had shocked the motocross community with its first four-stroke motocrosser, the revolutionary YZ400F. Then, three years later, they had done it again with the introduction of the industry’s first 250 four-stroke, the YZ250F. While there had been many competitive big bore four-strokes over the years (from manufacturers like BSA, Husqvarna, ATK and Husaberg just to name a few), no one had been able to crack the code for a competitive small-bore thumper. Modified XRs and KLXs were fun, but they were no match for a 125 two-stroke (much less a 250) on a motocross circuit.

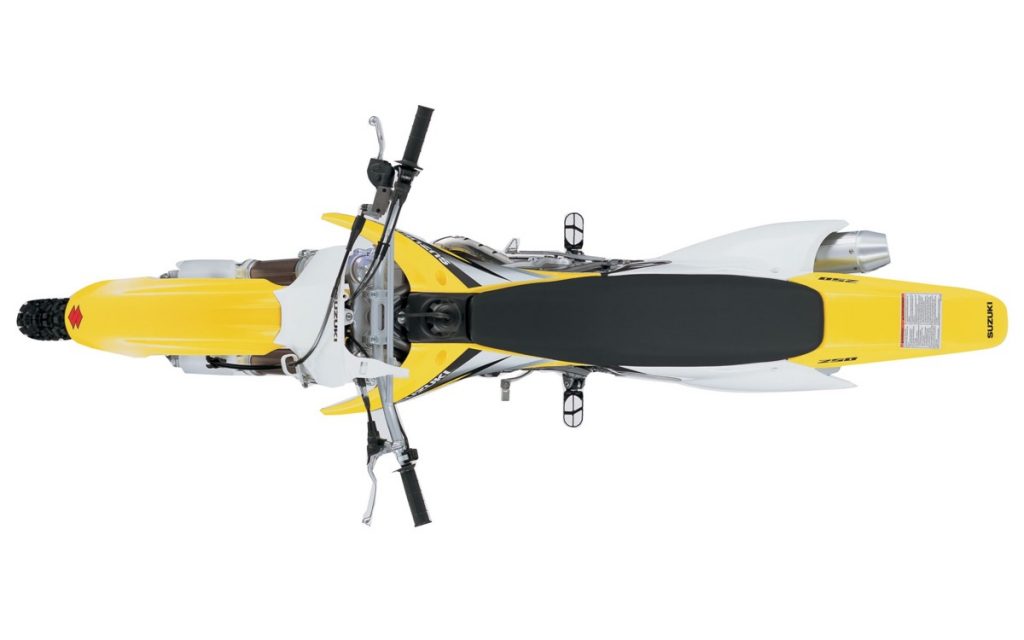

Doppelgänger: The Suzuki version of the KX250F differed only in the design of the radiator shroud and the color of the plastic. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The introduction of the Yamaha YZ250F changed all of that, and reshaped people’s expectations of what a valve-and-cam 250 could do. It was fast (mind-blowingly faster than any 250 thumper up to that point), had excellent handling and was super-easy to ride. In terms of peak power, it was not actually more potent than the best 125s of its day, but on the track its super-wide torque curve gave it a huge (and many would say, unfair) advantage.

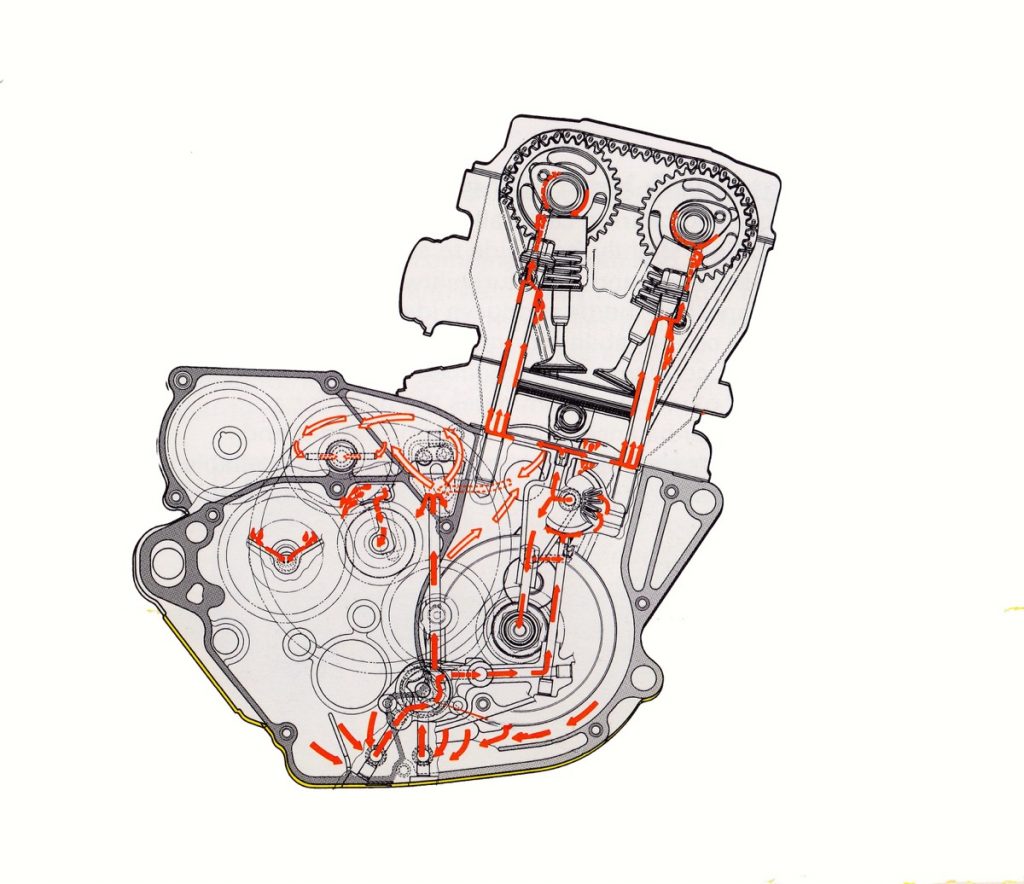

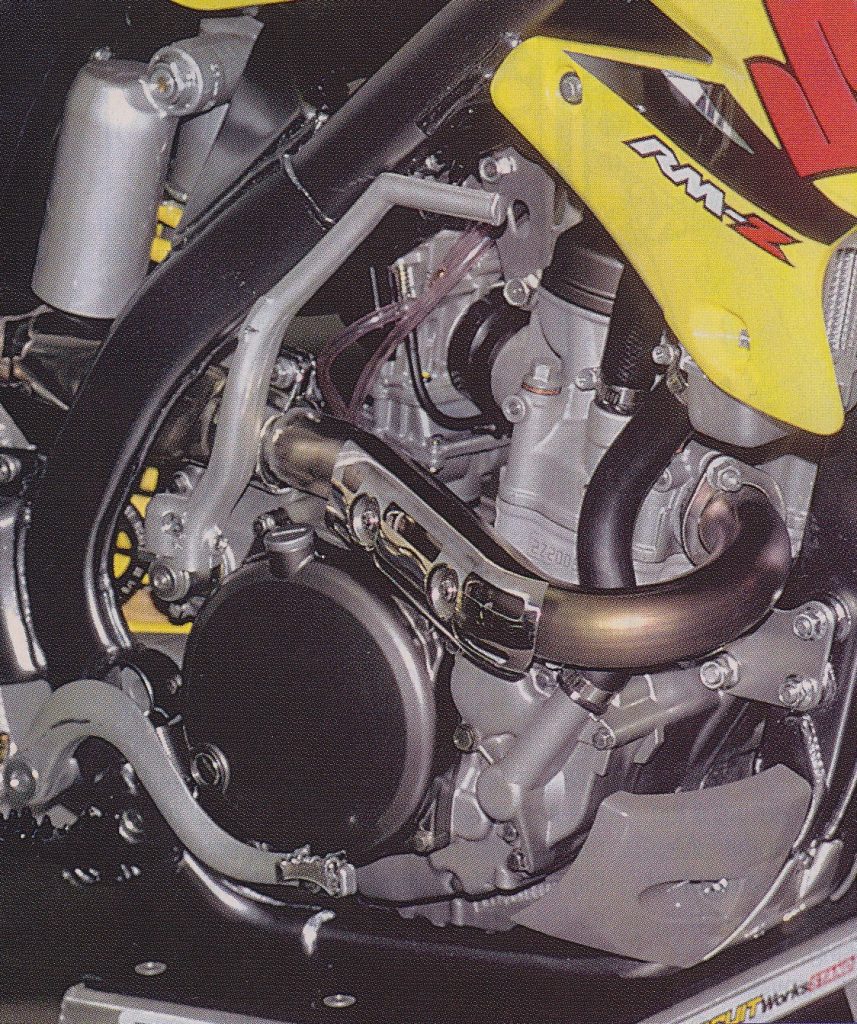

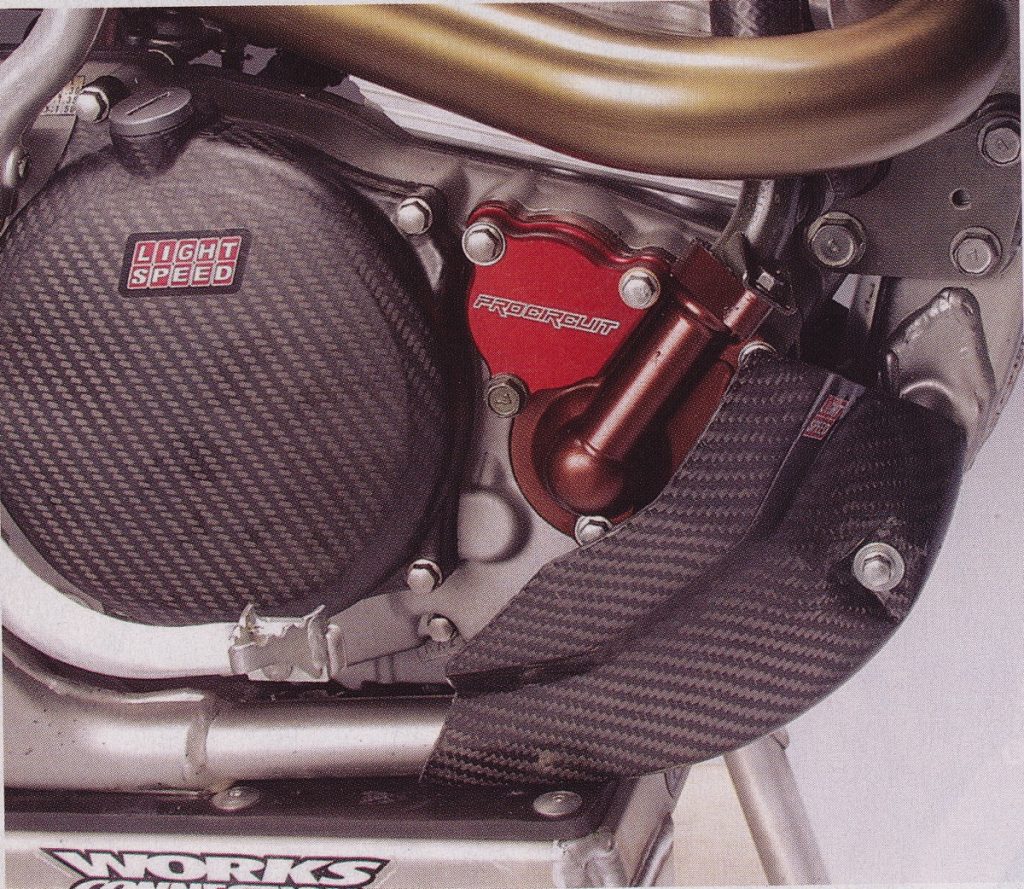

The motor on the new KXF/RM-Z was developed by Suzuki and featured several design innovations to make the motor as compact as possible. In an attempt to save weight and lower the center of gravity, the new motor featured an innovative “semi-dry-sump” configuration that allowed Suzuki to keep the crank as low as possible in the cases, while storing the majority of the oil in the upper transmission compartment. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The motor on the new KXF/RM-Z was developed by Suzuki and featured several design innovations to make the motor as compact as possible. In an attempt to save weight and lower the center of gravity, the new motor featured an innovative “semi-dry-sump” configuration that allowed Suzuki to keep the crank as low as possible in the cases, while storing the majority of the oil in the upper transmission compartment. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the original YZ250F was an undeniably incredible achievement, it was not without its problems. It was significantly heavier than a 125 (roughly 30 pounds more than the lightest bikes in the class), was prone to bogging at inopportune moments, and could be an absolute bear to get going once stalled. Even under the best of conditions, its NASA-like starting drill was a major pain, but once you threw in a hot motor and a panicked rider, it became a Freddy Krueger slasher film.

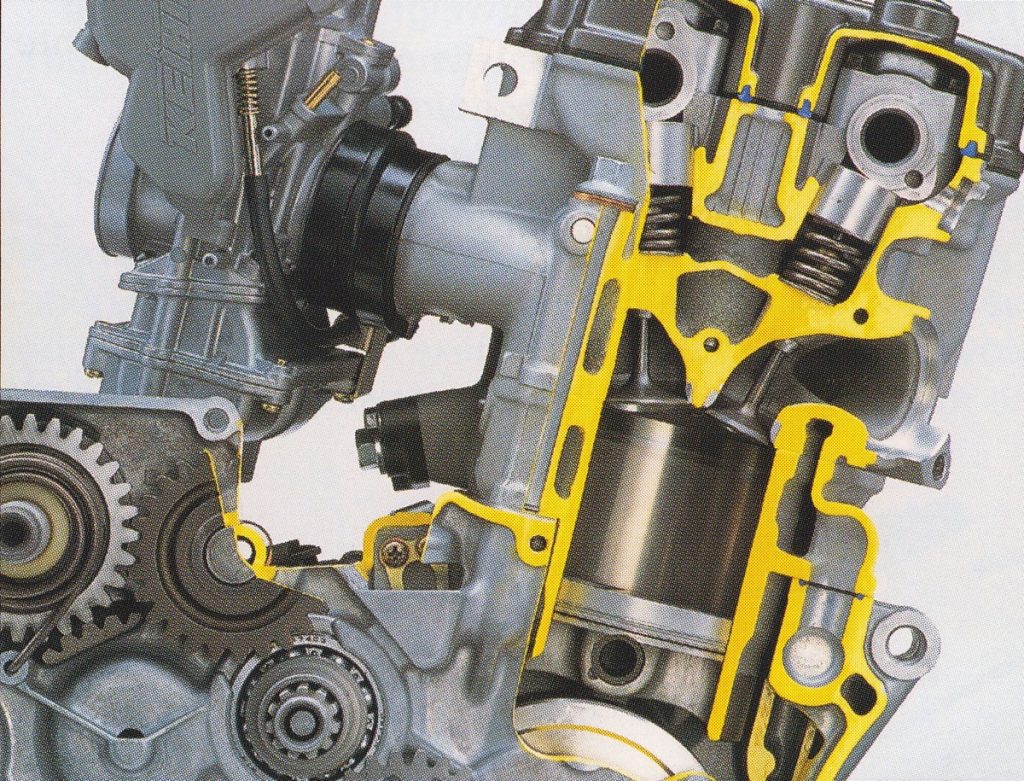

The top-end of the KXF/RM-Z used a dual-overhead-cam design similar to the ones found on most high-performance street machines. In order to reduce pumping losses and give the bike a “freer-revving” feel, Suzuki also took a trick from their GSX-R line by adding a one-way reed-valve (visible below the cam-chain tensioner in the above photo) that bled off internal pressure as the piston descended. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Even though the YZ250F was far from perfect, it was more than enough to signal a major paradigm shift in American racing. The YZ400F had been a hit in the market, but the 250 two-stroke had proven to be more than capable of fighting it off on the track. Aside from Doug Henry’s heart-warming 1998 250 National title, the YZ400F had remained more of an oddity than a game-changer in professional racing.

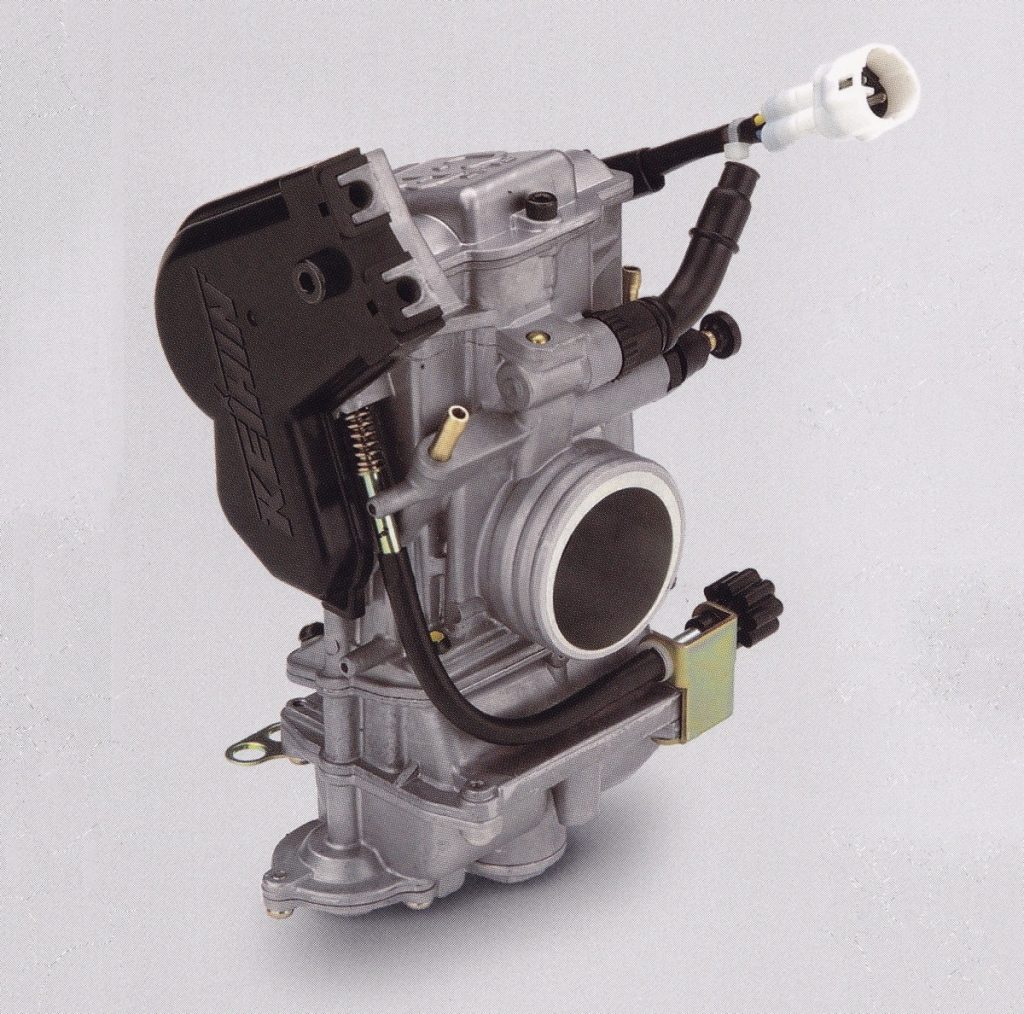

Before fuel injection made its way to motocross, the Keihin FCR carburetor was the gold standard of the four-stroke world. When properly jetted, this carb allowed four-strokes to provide a snappy and responsive style of power unheard of in the thumpers of yore. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With the YZ250F, however, things were different. Unlike the tank-like YZ400F and YZ426F, the YZ250F was light enough to be thrown around like a traditional two-stroke. Also, its problems with bogging and hiccupping were not as pronounced as on the bigger Yamaha thumpers. Maybe most significantly, its torque advantage over a two-stroke 125 was far more pronounced than the difference found on the bigger bikes. On a supercross track, a YZ250F could execute jumps that were just not imaginable on a 125 smoker. For better or worse, there was just no ignoring the impact the YZ250F was going to have on the sport moving forward.

Like the Yamaha and Honda four-stroke racers, the new RM-Z and KXF used an ultra-lightweight “slipper-style” piston to keep mass low and allow for the stratospheric rpm’s needed on the 250F. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As all this drama played out in the halls of the AMA and on the track, three of the Big Four Japanese manufactures were left scrambling to catch up. The one-two punch of the YZ400F and YZ250F had caught Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki completely flat-footed. By 2003, none of them had a YZ250F competitor and only Honda had anything ready to do battle with the YZ426/YZ450F.

While the new motor was a Suzuki design, the rest of the KXF/RM-Z package was pure Kawasaki. The frame, suspension and bodywork were all designed by the green team and shared a more-than-passing resemblance to the KX125 and KX250 two-strokes. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Faced with Yamaha’s huge head start in technology and the enormous resources of Honda Motor Corporation, Kawasaki and Suzuki looked at each other in 2001 and decided the best way to compete might be to actually join forces. Announced in August of 2001, the Kawasaki/Suzuki “strategic alliance” would allow both brands to fill out their portfolios with products from the other (hello yellow KX60s and green LT400 Quads) and reduce development costs by pooling resources to design and develop new products. The first of these products would be a jointly-designed competitor to Yamaha’s YZ250F.

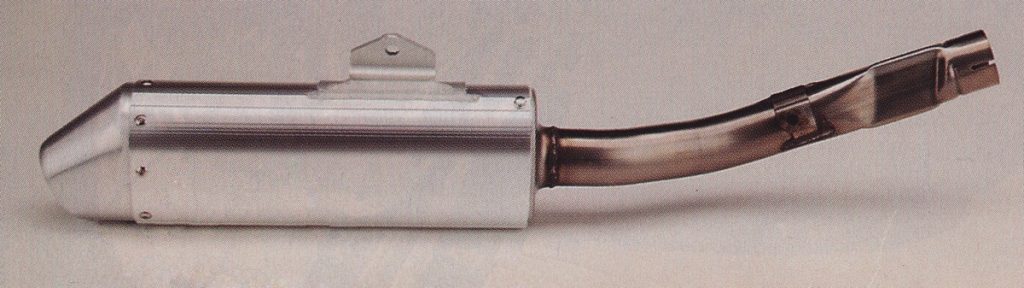

A change in FIM rules signaled an end to stingers and turned-down exhaust tips in 2004. The new regulation banned these mufflers and introduced the world to the safer, but much less interesting (in my opinion) closed-end cap. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With the new project, it was decided that Suzuki would handle designing the motor, while Kawasaki would develop the chassis and suspension. The bodywork, components, fit and feel would be pure Kawasaki, with the motor being the only real Suzuki contribution. Kawasaki would even build the bike, with both green and yellow versions rolling off the same assembly line at Kawasaki Heavy Industries.

The frame used on the KXF/RM-Z stuck to the steel perimeter design Kawasaki had employed on its motocross machines since 1990. Even though the overall design was familiar, a new “D-Section” on the top of the frame narrowed the pilot compartment considerably over previous perimeter designs. Photo Credit: Suzuki

When designing the new engine, Suzuki relied both on their extensive road-racing experience and an analysis of what had worked and not worked on Yamaha’s 250F. The basic motor configuration copied the short-stroke design used on the YZ-F (right down to the exact same 77mm x 53.6mm bore and stroke), but differed by using four valves instead of the Yamaha’s five in the head. Like the YZ-F (but unlike the single-cam Hondas), the RM-Z/KZF’s four titanium valves were actuated by dual cams and a shim-and-bucket system. In order to attain the stratospheric rev limits and quick spool-up necessary to make a small-bore four-stroke effective, Suzuki decided to stick with a lightweight “slipper” piston for the top end.

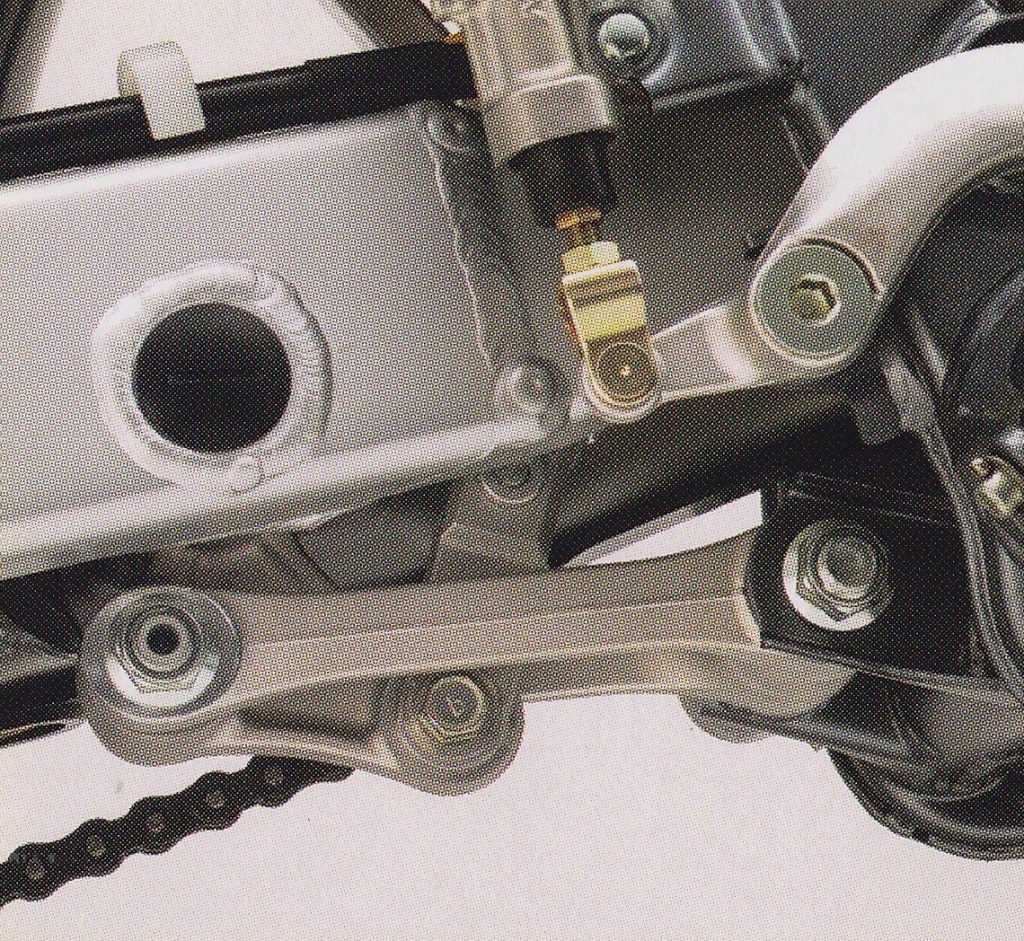

A new Uni-Trak linkage for 2004 repositioned the mounts from the frame to the swingarm to reduce fore-aft movement of the shock as it moved through its travel. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Where the new Suzuki motor differed was in the configuration of the bottom end. When designing the original YZ-F, reliability had been a major concern, so Yamaha spec’d a dry-sump oil system. This allowed the bike to both carry more oil, and better cool it, by circulating oil through the frame. The downside of the dry-sump system was weight and complexity. With the CRF, Honda had taken a feather from the old BSA days and separated the oil and transmission fluid. This was done to prevent cross-contamination from the transmission and clutch from making its way into the top end. While good at keeping things separate, the disadvantage of the Honda system was less cooling for the oil and diminished overall capacity.

The new Kawasaki KX250F proved extremely successful in the hands of Pro Circuit rider Ivan Tedesco. Tedesco would take the all-new machine to wins in the first five rounds of the series on his way to the 2004 125 West Coast Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With the KXF/RM-Z, the Suzuki engineers decided to go with a unique hybrid system they coined the Suzuki Advanced Sump System (SASS). This “semi-dry-sump” system placed the crank and transmission in separate compartments (like a Honda) and featured two oil pumps, one for scavenging and one for pumping. In the SASS, the transmission acted as the oil tank, with both the top and bottom end separated by a reed-valve, but sharing the same oil reserve.

On the track, the new KXF/RM-Z powerplant offered a very different style of power than the Yamaha YZ250F. Where the YZF thrived on rpm and needed to be ridden like a 125, the new Kawazuki twins preferred to be short-shifted and ridden more like a small 450. Most of its power was in the low-to-mid range and wringing it out only made it go slower. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The advantage of this system was that it allowed Suzuki to place the crank very low in the motor (to keep rotating mass as low as possible), while not suffering the typical pumping losses due to the crank being bathed in oil. By using a scraper and a scavenging pump, engineers were able to keep the crank free of excess oil and allow it to rev more freely. The new motor also saved weight and reduced complexity by doing away with external oil lines in favor of internal oil passages and hollowed-out bolts that doubled as carriers of oil to the head.

Both the RM-Z and KXF featured lightweight titanium head pipes connected to aluminum mufflers. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In order to reduce crankcase pressure, Suzuki also developed an interesting reed-valve arrangement they coined the Suzuki Active Vent System (SAVS). Pioneered on their GSX-R road racers, the SAVS utilized a one-way valve to bleed off internal pressure as the piston descended in the cylinder. By lowering internal pressure in the down-stroke, the motor could be made to respond quicker and rev more freely.

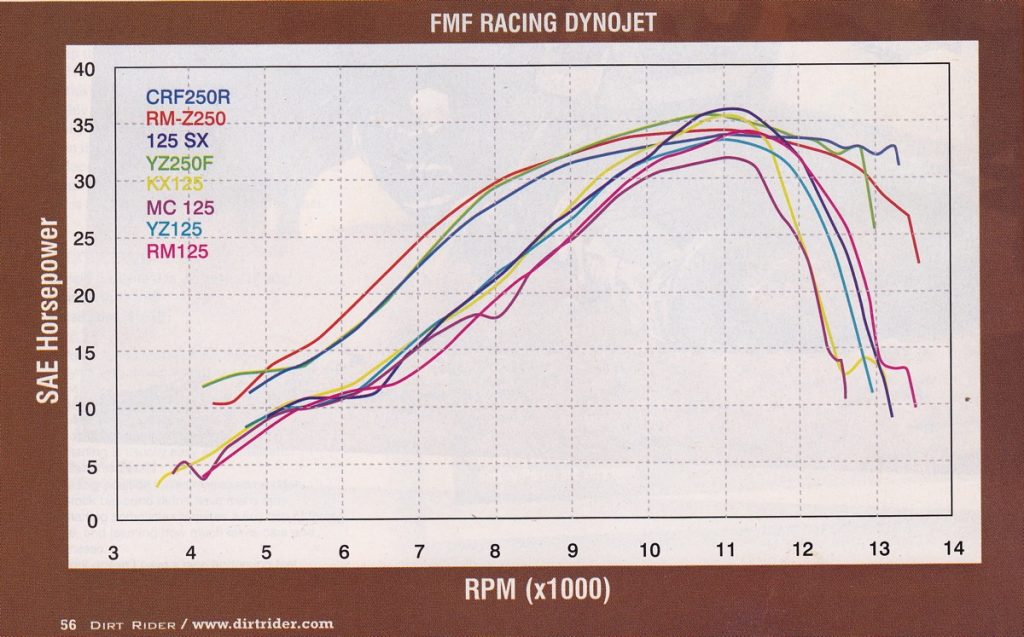

As this dyno chart reveals, all of the RM-Z’s (and KXF’s) power advantage was in the lower portion of the powerband. Once past the midrange, the YZ250F and several 125s pulled ahead. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Finishing off the motor were a close-ratio five-speed transmission, high-tech electronic ignition (with 3-D mapping and different curves based on gear and throttle position), 37mm Keihin FCR carburetor and automatic decompression system. The exhaust featured a lightweight titanium head pipe and FIM-legal enclosed-cap alloy muffler. Overall, it was a thoroughly modern four-stroke motocross motor.

Not surprisingly, the handling on the new KXF/RM-Z was similar to Kawasaki’s two-strokes. That meant good stability, but not a lot of precision in the turns. Keeping the gas on and steering with the rear was the most effective way to get the green (and yellow) machine heading in your intended direction. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the chassis department, Kawasaki chose to stick to what they knew by dialing up a twin-spar steel perimeter frame very similar to what you could find on their KX125 and KX250 two-strokes. Overall chassis dimensions were unique, however, and the new frame featured special “D-section” spars on the top to narrow the layout at the seat-tank juncture. The bottom of the frame was also slightly narrower, with the footpegs mounted 3mm higher than on the KX250 to improve cornering clearance.

While the new motor was competitive on the track, its significant mechanical maladies left many buyers longing for the near indestructability of Yamaha’s impressive four-strokes. There were issues with the valves, buckets, valve springs, transmission and clutch…as well as a chronic over-heating problem and a propensity to eat oil at an accelerated rate. When it ran, it was fun, but keeping it that way took mega dollars and constant vigilance. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the suspension front, Kawasaki once again handled development for the twin machines. Up front, the green team went with a set of 48mm Kayaba cartridge forks. These units featured 11.8” of travel with 16 adjustments for compression and rebound. Internally, the forks featured a “semi-sealed” cartridge that was designed to bleed off excess pressure during travel and a bladder system that was designed to reduce bottoming under heavy loads.

The 48mm Kayaba forks found on the KXF/RM-Z were softly sprung, and at times, harsh in action. Most novice riders could live with their performance, but anyone above the intermediate class was likely to want stiffer springs and a revalve. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Out back, Kawasaki once again enlisted Kayaba to handle the shock duties (Suzuki’s RM125 and RM250 used Showa components in 2004). The single KYB damper offered 12.2” of travel and 16 adjustments for compression and rebound. Unlike previous KX models, which anchored the linkage to the frame, the new KXF (and RM-Z) moved the linkage anchor point to the swingarm. This was done to reduce front-to-rear movement of the shock and increase traction and stability under power.

A lot of the gripes people had with the forks probably had something to do with the KXF/RM-Z’s shock. That new linkage that Kawasaki was so proud of jacked the rear up in the air and gave the bike a decidedly droop-nose stance. This, combined with the shock’s mediocre action, put a lot of stress on the front forks. Thankfully, the aftermarket was quick to pounce on this deficiency and there were several accessory links that evened out the bike’s stance and smoothed out its performance. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As to the rest of the bike, it was 100% Kawasaki. The brakes, bodywork, components and switchgear were pure KX. This was not necessarily a bad thing, but if you had any two-stroke RMs in your stable, it was best not to count on swapping any parts in a pinch (even the RM triangle stand would not fit in the RM-Z axle). The aesthetics of the two machines were nearly identical, with the only differentiators being color and slightly different radiator shrouds and graphics. Both bikes were certainly good looking, but the RM-Z did not really look all that much like the two-stroke RMs.

PulpMX’s own Kris Keefer putting the all-new Suzuki RM-Z250 through its paces in 2004. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

As with any race machine, the true test of the twin’s performance was on the track. There, they were actually fairly successful for a first outing. The new 249cc DOHC motor put out a solid and fun-to-ride style of power that was effective, but very unlike the high-rpm song of the YZ250F. Most of the KXF/RM-Z’s thrust was found in the low-to-mid portion of the powerband and the bikes preferred to be short-shifted rather than revved out. Unlike the YZF, which was most effective when ridden like a 125, the Kawazuki twins actually went slower if you held it on until the paint dried.

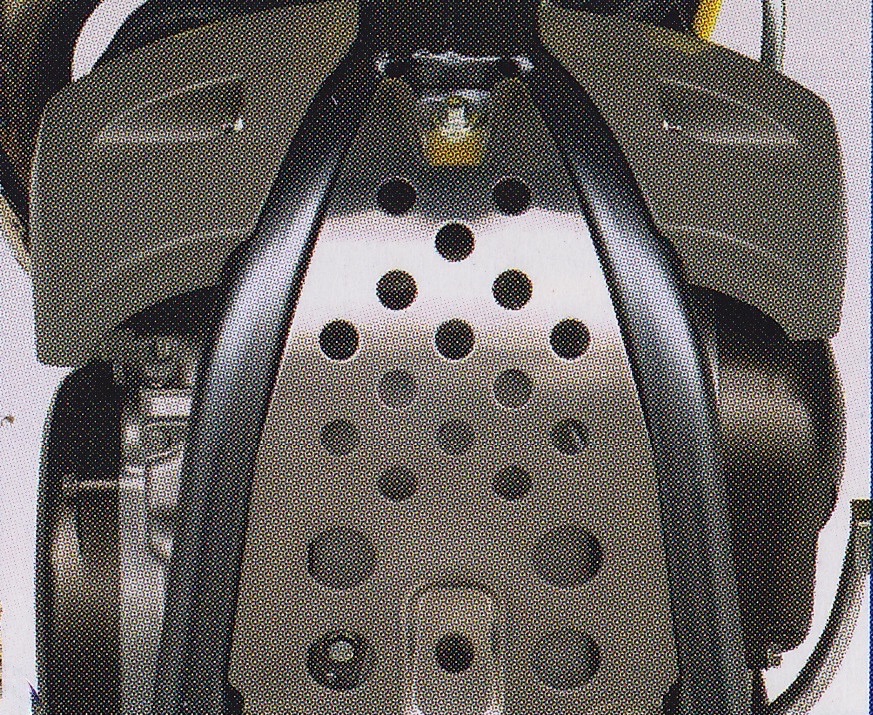

Unlike their two-stroke models, both the KX250F and RM-Z250 featured sturdy skid plates and engine guards as standard equipment. Photo Credit Suzuki

On the track, the twin’s strong low-end pull and healthy midrange burst could be very effective. If ridden properly, it propelled the bikes quickly from turn to turn and made them a lot of fun to ride. There was more than enough thrust to clear jumps out of turns and a lot more “grunt” than what people had come to expect from a 250 four-stroke. This made the twins very novice-friendly, but did limit its appeal to the fast guys.

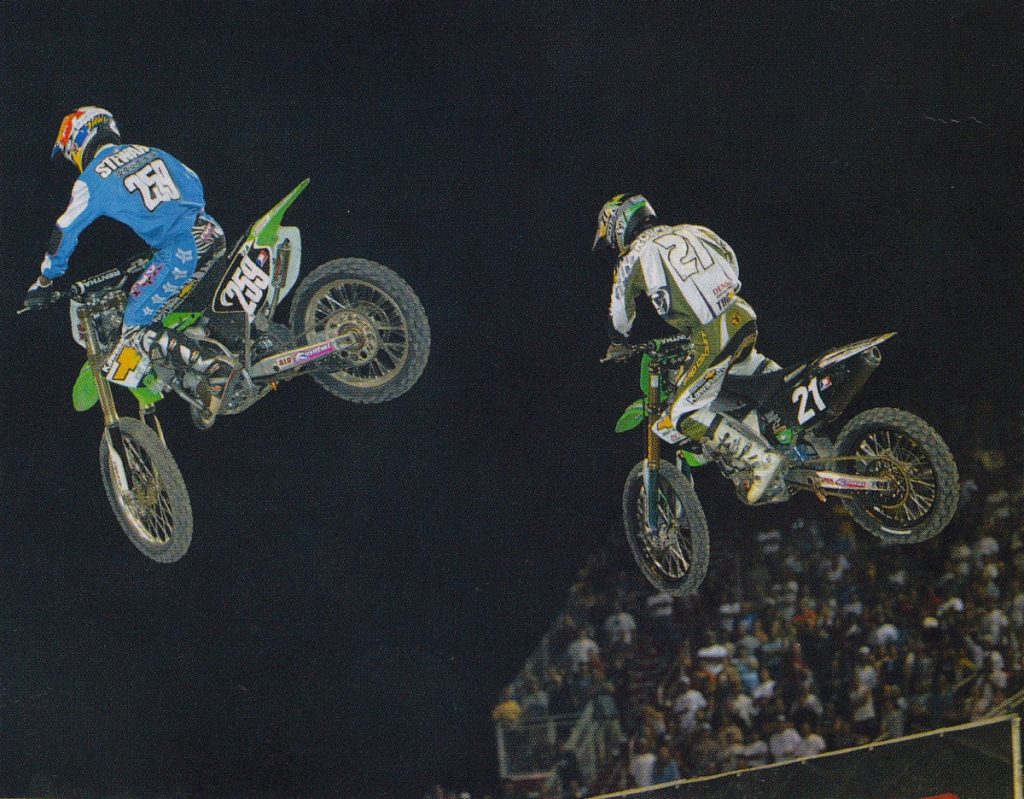

At Las Vegas and Hangtown in 2004, Kawasaki’s James Stewart and Pro Circuit’s Stephane Roncada engaged in a great clash of old and new technology. In both cases, the two-stroke of Stewart came out on top, but the obvious advantages of the four-stroke made the battle far closer than most would have predicted. Photo Credit: Steve Bruhn

For those accustomed to 125 two-strokes or Yamaha’s 250F, the KXF/RM-Z could be a more frustrating experience. Compared to the Honda or Yamaha 250F, the Kawasaki and Suzuki offered a narrower powerband that revved slower and signed off sooner. It also vibrated a lot more (Suzuki had decided to forgo a counter-balancer in the motor design) and tended to run VERY hot when pushed. Just letting it idle on the starting line for 30 seconds was enough to boil it over and fast guys quickly found the limits of its cooling system. Adding a higher-pressure radiator cap helped somewhat, but there was no getting around the fact that Suzuki had underestimated the thermal loads this new machine was going to be subjected to.

Fixer Upper: While the KXF/RM-Z’s many shortcomings were a downer for consumers, they certainly proved to be a boon for the aftermarket. Companies like Pro Circuit offered everything from valve springs to suspension links to help performance and improve reliability. Photo Credit: Transworld Motocross

Unfortunately, overheating was not the last of the new machine’s mechanical woes. The cams, valve springs, valves and buckets all proved to be very short-lived. After about ten hours of hard use, the valve springs started to sack out and the buckets developed small deformations that caused them to shatter. The cams themselves also proved to be too soft for sustained high-rpm use and were prone to failures if you let the oil level drop just a bit. When this happened, the plain bearing on the cam could run dry, causing a seizure. This oil problem turned out to be a major issue on the twins, as both bikes liked to eat oil at a sustained rate and carried very little in reserve. With just over a quart of capacity, it was critical to watch this like a hawk.

While the KXF/RM-Z’s new exhaust could pass the AMA’s arcane sound tests, in the real world, it proved an ear-splitting annoyance. At the rpm levels that riders actually used, its exhaust note was substantially more offensive (and that is saying something for a four-stroke) than everything else in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Just maintaining the proper oil level turned out to be another problem area, as the sight glass used for oil level inspection proved both fragile and potentially inaccurate. Because of the odd semi-dry-sump configuration, proper oil readings required a specific procedure, and If you didn’t follow it, the window could lead you to believe the oil was low. With no dipstick and a HUGE fear of letting the oil drop too low, many people erred on the side of caution and ended up overfilling the motor with oil. Unfortunately, if this was done, the bike would start blowing seals. Ugh…

Another major gripe on the 2004 KXF/RM-Z was Suzuki’s idiotic decision to integrate the oil filter and water pump into a single unit. This meant that when you wanted to change the oil (something you probably should do after every ride), you also had to drain the coolant. Thankfully, companies like Pro Circuit quickly realized the idiocy of this arrangement and introduced water pumps that separated the two covers. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Just changing the oil was also a nightmare, due to Suzuki’s inscrutable decision to incorporate the oil filter and water pump into one unit. This meant that if you wanted to change the oil, you also had to drain the coolant. Thankfully, aftermarket companies like Pro Circuit were quick to come out with improved water pumps that helped the overheating issue and added a separate cover for the oil filter.

Probably the KXF/RM-Z’s most glaring flaw was the capacity (or lack thereof) of its cooling system. Just letting the bike idle for a minute was enough to cause it to boil over and the smell of hot coolant was a constant companion. Screwing on a higher-pressure radiator cap helped forestall the inevitable coolant puking, but only temporarily. For hard-core racing, a switch to higher-capacity aftermarket radiators (like these FPS Racing units) and an aftermarket water pump were a must.

As if the overheating and fragile top-end were not enough, there were also problems with the bottom end of the new motor. Both the transmission and clutch proved delicate and failures were common. Third and fourth gears liked to grenade on hard-ridden units and the KX125-sourced clutch was absolutely not up the stresses put on it by the torquier four-stroke motor. If ridden hard, the clutch began slipping almost immediately, further exacerbating the motors overheating issues. Thankfully, there were aftermarket fixes for nearly all of these issues, but it was likely to cost you twice what you paid for the bike to address all of them.

In the Nationals, Suzuki’s Davi Millsaps and Broc Hepler (pictured) campaigned the new RM-Z. While not up to keeping James Stewart in sight, Broc’s solid second overall place in the standings proved the RM-Z could be competitive against the other brands. Photo Credit: Steve Bruhn

While the motor was a real mixed bag, the rest of the KXF/RM-Z was a pretty solid package. As long as you did not buy an RM-Z then actually expected it to handle like a Suzuki, you were likely to be happy with the twin’s handling. Like most Kawasakis of the era, the new twins offered a conservative handling package that offered good (but not great) turning and decent stability. It was not nearly as precise in the turns as an RM, but it was also less prone to high-speed wobbles. The ergonomics of the two were also liked by most, with a slim feel and compact dimensions. The low center of gravity in the motor was also noticeable on the track and both machines felt significantly nimbler than Yamaha’s top-heavy YZ250F.

In an effort to keep the terminally overheating twins in one piece, some riders resorted to running massive air scoops like the old air-cooled 500cc two-stroke days. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the suspension front, both bikes were passable, but in need of work. The forks offered decent bottoming resistance and acceptable action for those within the bike’s targeted weight group, but faster or heavier riders found them too soft. Some riders also complained of harshness, but others did not seem to notice. For novice use, they were good, but fast guys were likely to want a revalve and spring swap. Another complaint some riders voiced was with the ride height. In stock condition, the RM-Z and KXF forks sat low in the travel and helped give the bike a “stinkbug” stance. Part of this problem was also the new Uni-Trak linkage, which jacked up the rear of the bike like a jet-powered Funny Car.

At the final round of the 2004 125 Motocross series, James Stewart finally parked his trusty KX125 in favor of the new KX250F. After finishing out the season with another dominating 1-1 finish, he commented on the new bike on the podium by stating “If I was riding this thing all year I’d be fat and out of shape!” Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With this low-in-the-front and high-in-the-back stance, the bike felt very unbalanced and leveling it out was critical to getting the most out of the bike’s chassis. One cheap fix was to slide the forks down in the clamps, but the best solution was to pop for an aftermarket link from someone like Pro Circuit or RG3 that leveled out the chassis.

Any rider who purchased the new RM-Z250 expecting it to feel like a traditional Suzuki was going to be in for a disappointment. Virtually nothing was interchangeable with the two-stroke RMs and the bike exhibited none of the razor sharp turning manners and feathery feel the yellow machines were famous for. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

As to the shock itself, it offered only mediocre action. When cold, it was over-damped and harsh. Once hot, the damping went away and blew it through the stroke. At moderate speeds, it worked well enough, but once you started to push, its quickly became a handful. For a novice or beginner, it was usable, but anyone above that speed was likely to want an aftermarket link and a revalve.

Overall, the KXF/RM-Z experiment turned out to be an unsatisfactory one for both Kawasaki and Suzuki. While the new machines did get them in the four-stroke game, the twin’s many problems left both manufacturers with hard feelings that would contribute to the end of their alliance. In the end, neither one was particularly happy with the outcome of their marriage, and in 2005, the two decided to terminate their joint development agreement. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Even though the original KXF and RM-Z were far from perfect, they still proved surprisingly popular. The market was hot for four-strokes and customers were keen to snatch them up, regardless of the machine’s shortcomings. In their favor, they were torquey, fun-to-ride bikes that could certainly win in the right hands (Ivan Tedesco took one to the 125 West Coast Supercross title in 2004), but their many mechanical maladies detracted from their appeal. For play riding and occasional racing, they were solid choices, but for serious racers, there were better choices available.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com