For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s second 250 machine of 1978, the all-new RM250C-2.

In 1978, Suzuki released two RM250 models. Only seven months after the RM250C made its debut, the majorly-revised C-2 hit the showrooms with all-new bodywork and updated suspension. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1978, Suzuki released two RM250 models. Only seven months after the RM250C made its debut, the majorly-revised C-2 hit the showrooms with all-new bodywork and updated suspension. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The seventies were a great time to be a Suzuki fan. In Europe, they dominated the Grand Prix standings with riders like Roger DeCoster, Joel Robert, and Gaston Rahier at the controls. In America, Pennsylvania’s Tony DiStefano piloted the yellow machines to three straight 250 Motocross titles in ’75, ’76, and ’77. On the track they were dominant, and in the showrooms, they had the cachet of a winner. To put it frankly, if you wanted to win in the mid-seventies, you could not do much better than a Suzuki RM.

In the seventies, Suzuki was a title-winning machine with riders like Roger DeCoster at the controls. Photo Credit: Michael Stusiak

In the seventies, Suzuki was a title-winning machine with riders like Roger DeCoster at the controls. Photo Credit: Michael Stusiak

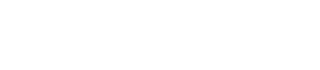

For Suzuki, this dominance at the production level had not come easy. Early efforts like the TM400 Cyclone had been notable, but for all the wrong reasons. In spite of their success on the world stage, Suzuki had found it difficult to translate GP wins into production excellence. The Cyclones, Champions, and Challengers looked like the machines of the GP heroes but ran like the poorly-executed budget facsimiles that they were.

While early Suzuki ads proclaimed their motocross models to be “race ready right out of the crate,” the reality was quite different. It was not until 1976, with the introduction of the first RM250, that Suzuki could finally back up that boast in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While early Suzuki ads proclaimed their motocross models to be “race ready right out of the crate,” the reality was quite different. It was not until 1976, with the introduction of the first RM250, that Suzuki could finally back up that boast in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Thankfully, however, all that changed in 1975 with the introduction of Suzuki’s new RM series. Light, fast, and well-suspended, the all-new RM125 was far more serious than any of the lackluster TMs it replaced. In 1976, Suzuki filled out the RM lineup with a pair of all-new machines aimed at dominating the 250 and 500 class standings. Billed as “Works Replicas”, the all-new RM250A and RM370A featured laid-down shocks, powerful case-reed two-stroke motors and sturdy chrome-moly steel frames. Unlike past Suzuki efforts, these new RMs actually lived up to their Works Replica names and offered class-leading performance.

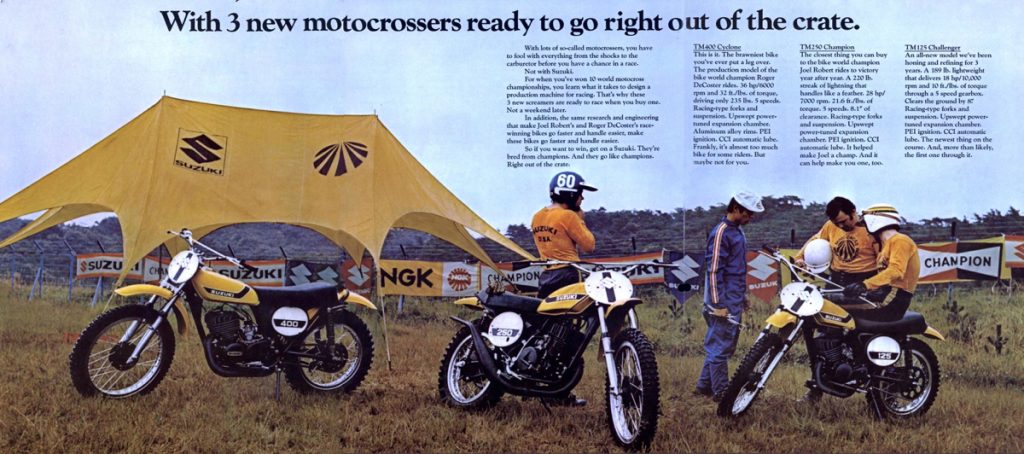

The addition of a beefy alloy swingarm was the thrust of Suzuki’s ads for the new ’78 ½ RM250C-2.

The addition of a beefy alloy swingarm was the thrust of Suzuki’s ads for the new ’78 ½ RM250C-2.

By 1978, the RM250 was firmly entrenched as one of the best bikes in the class, but after two years at the front, it was starting to feel a little heat from the competition. All-new bikes from Honda, Kawasaki, and a majorly-renovated YZ250 were set to steal the thunder from the reigning national championship machine. With this in mind, Suzuki pushed their development program forward and decided to release a mid-season update to their ‘78 RM250C.

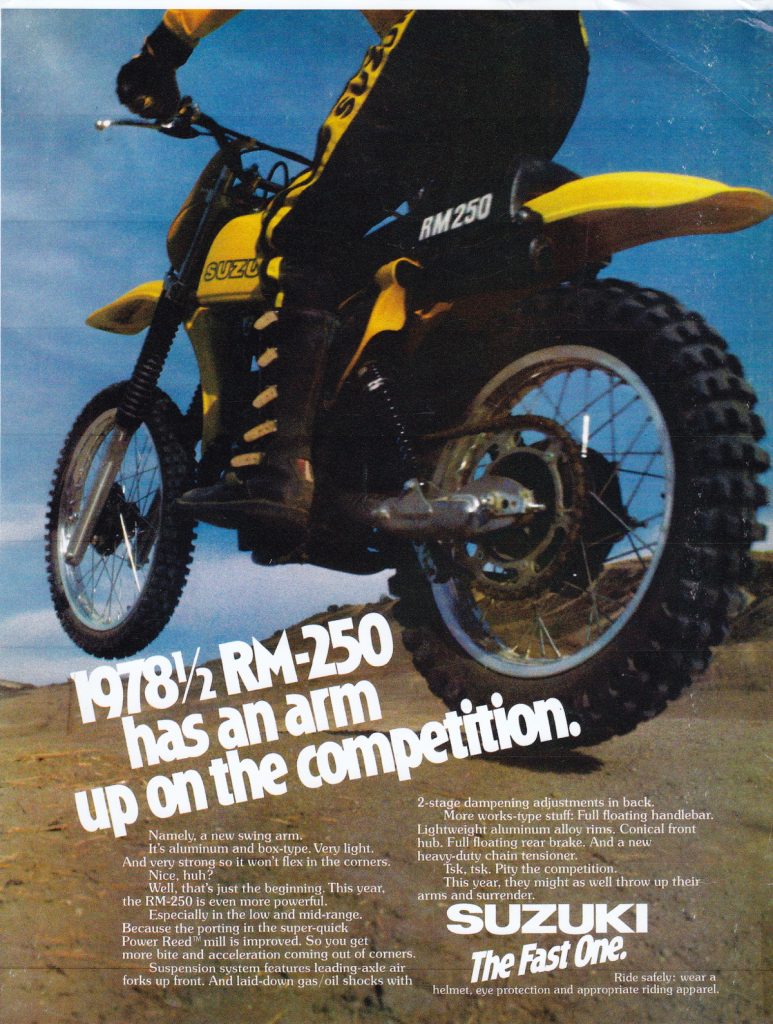

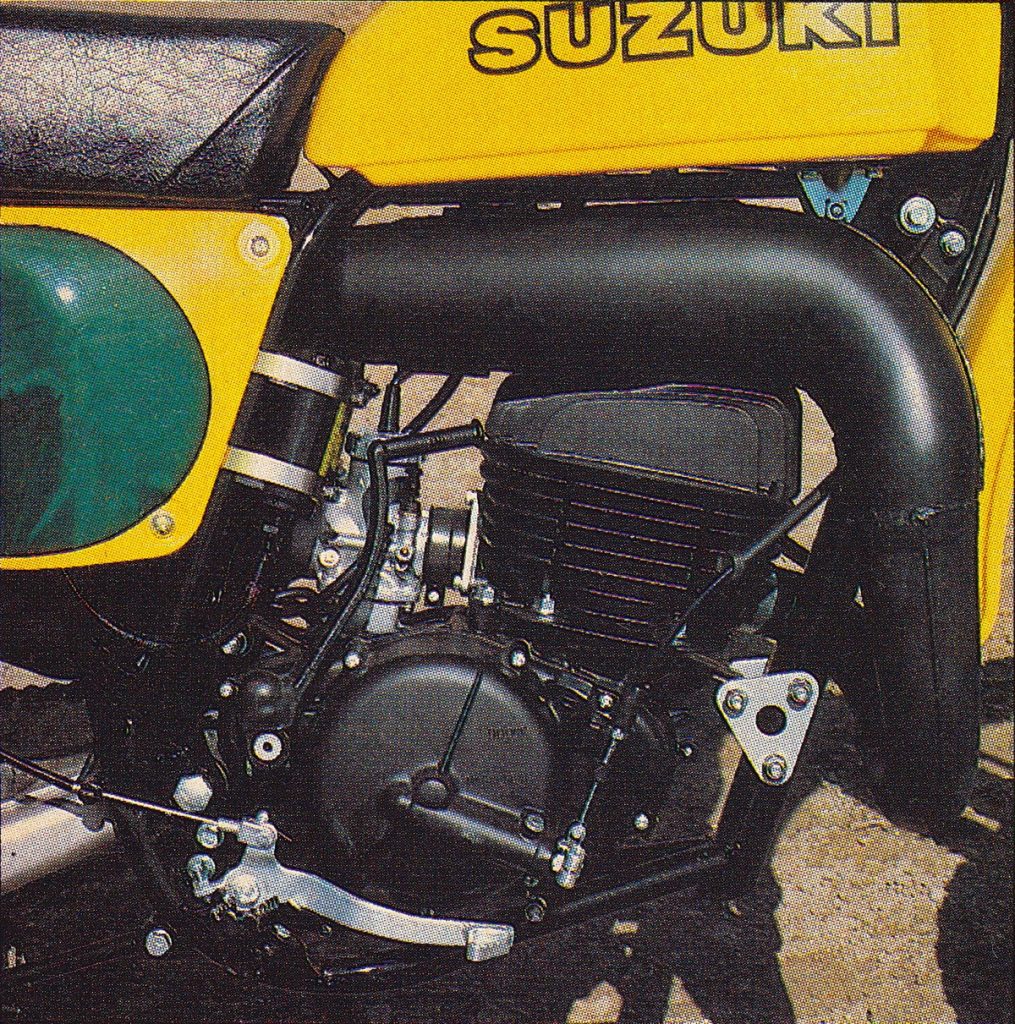

The RM250C-2 used a unique semi-case-reed intake system Suzuki called the “Power Reed”. The Power Reed was basically a hybrid between the old piston-port and new reed-valve systems. By combining them, Suzuki hoped to get both the responsive low-end of the reed valve and screaming top-end of a piston-port design. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RM250C-2 used a unique semi-case-reed intake system Suzuki called the “Power Reed”. The Power Reed was basically a hybrid between the old piston-port and new reed-valve systems. By combining them, Suzuki hoped to get both the responsive low-end of the reed valve and screaming top-end of a piston-port design. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Dubbed the 1978 ½ RM250C-2, this new model maintained the basic motor and frame of the ’78 “C” model, but added new bodywork and majorly-updated suspension. The new bodywork featured revised fenders, an all-new tank and a shorter (19mm) seat for improved ergonomics. The new fenders featured a wider profile for increased mud protection and reinforcement ribs to reduce flex. The new tank incorporated revised styling and a change in material from aluminum to plastic.

A common aftermarket upgrade at the time, the addition of a stock alloy swingarm meant that was one less item a Suzuki pilot had to spring for in 1978. Photo Credit: Cycle World

A common aftermarket upgrade at the time, the addition of a stock alloy swingarm meant that was one less item a Suzuki pilot had to spring for in 1978. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the suspension end, the RM250C-2 featured all-new components both front and rear. Up front, new forks maintained the same 9.8 inches of travel but offered increased internal overlap to reduce binding and flex. New valving also increased rebound control slightly and new springs stiffened the ride over the C model. Internally, the new forks also increased overall oil capacity by 19cc. As on the C model, the new C2 offered no external adjustments for damping, but the ride could be fine-tuned by adding or subtracting air pressure via a Schrader valve on top of each fork.

The new forks on the C-2 maintained the same 9.8-inches of travel of the C model, but offered more internal overlap (to decrease flex and binding) and an increase in air and oil volume. In order to accomplish this, Suzuki extended the top of the forks and redesigned the triple clamps to set the bars back and out of the way. Photo credit: Mecum

The new forks on the C-2 maintained the same 9.8-inches of travel of the C model, but offered more internal overlap (to decrease flex and binding) and an increase in air and oil volume. In order to accomplish this, Suzuki extended the top of the forks and redesigned the triple clamps to set the bars back and out of the way. Photo credit: Mecum

Out back, all-new shocks punched out nearly an inch more travel than the 250C. The C-2’s DeCarbon-type dampers featured remote reservoirs, revised damping, and a competitive 9.7 inches of travel. These Kayaba-built units also included increased fluid capacity to reduce fading and two adjustable settings for rebound (soft and hard). This was a pretty trick feature in 1978 and only the Yamaha offered anything similar. In order to make this adjustment, you had to remove the shock spring and twist the shock body. While not particularly convenient, it was nice to have this option available.

All-new plastic on the RM250C-2 featured strengthening ribs to prevent flex and a wider profile for better mud protection. Photo credit: Mecum

All-new plastic on the RM250C-2 featured strengthening ribs to prevent flex and a wider profile for better mud protection. Photo credit: Mecum

In addition to the all-new shocks, the rear of the C-2 featured Suzuki’s first use of an alloy swingarm on their 250 machines. Similar in appearance to the steel unit it replaced, this alloy design offered improved strength and reduced weight. Finishing out the rear of the C-2 was a trick full-floating brake design that looked to improve suspension performance by isolating the shocks from the torque forces of the wheel under braking.

Subtle porting changes made to the C-2’s 246cc power plant equaled a whopping five horsepower boost over the mellow RM-C.

Subtle porting changes made to the C-2’s 246cc power plant equaled a whopping five horsepower boost over the mellow RM-C.

In the motor department, the C-2 offered a refined version of the basic RM250C package. The bore, stroke, and overall displacement remained unchanged from the C model’s 67 x 70mm and 246cc. Porting, however, was altered to improve flow and additional finning was added to the motor to keep temps under control. On the intake side, the C2 continued to use the semi-case-reed “Power Reed” induction that Suzuki had employed on the RMs since 1976. In the bottom end, the crank, transmission, and clutch remained unchanged from the ’78 RM250C.

With riders like Tony DiStefano aboard, Suzuki was a powerhouse both here and abroad in the mid-seventies. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With riders like Tony DiStefano aboard, Suzuki was a powerhouse both here and abroad in the mid-seventies. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the track, the ’78 ½ RM250C-2 offered a significantly different experience from its seven-month-older brother. By reshaping the transfer ports, Suzuki’s engineers were able to coax an astounding five additional horsepower out of the C-2’s mill. Most of those additional ponies were on the top end and the new motor pulled far stronger and longer than the old version had. Whereas the ‘78 C model had offered a torquey low-to-mid delivery, the new C2 did its best work from the midrange on up. It still ran well down low, but now it pulled well past the point where the old model had demanded another shift. For pros, these changes were a welcome improvement, but some less-skilled pilots preferred the mellower and easier-to-manage C power plant.

The Suzuki’s 36mm Kayaba forks were both smaller in diameter and less long-legged than the competition in 1978. In spite of these deficiencies, however, they delivered competitive performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The Suzuki’s 36mm Kayaba forks were both smaller in diameter and less long-legged than the competition in 1978. In spite of these deficiencies, however, they delivered competitive performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

With good low-end, a strong midrange and a newly-found pull on top, the C-2 offered one of the best power packages of the ’78 250 class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

With good low-end, a strong midrange and a newly-found pull on top, the C-2 offered one of the best power packages of the ’78 250 class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the suspension and handling end of things, the C2 was improved, but not night-and-day better than the C. At 36mm in diameter, the new RM’s forks were smaller than the 37mm and 38mm units found on the all-new CR and revamped YZ. Their 9.8-inches of travel were also significantly less than the whopping 11.5-inches of movement found on the Honda. In spite of these deficiencies, however, the RM’s Kayaba forks worked well with a little fine tuning. In stock condition, they were a bit stiff for non-pros, but well-liked by fast pilots. With a switch from the stock 15-weight oil to a lighter 10-weight, they were proclaimed some of the best forks in the class.

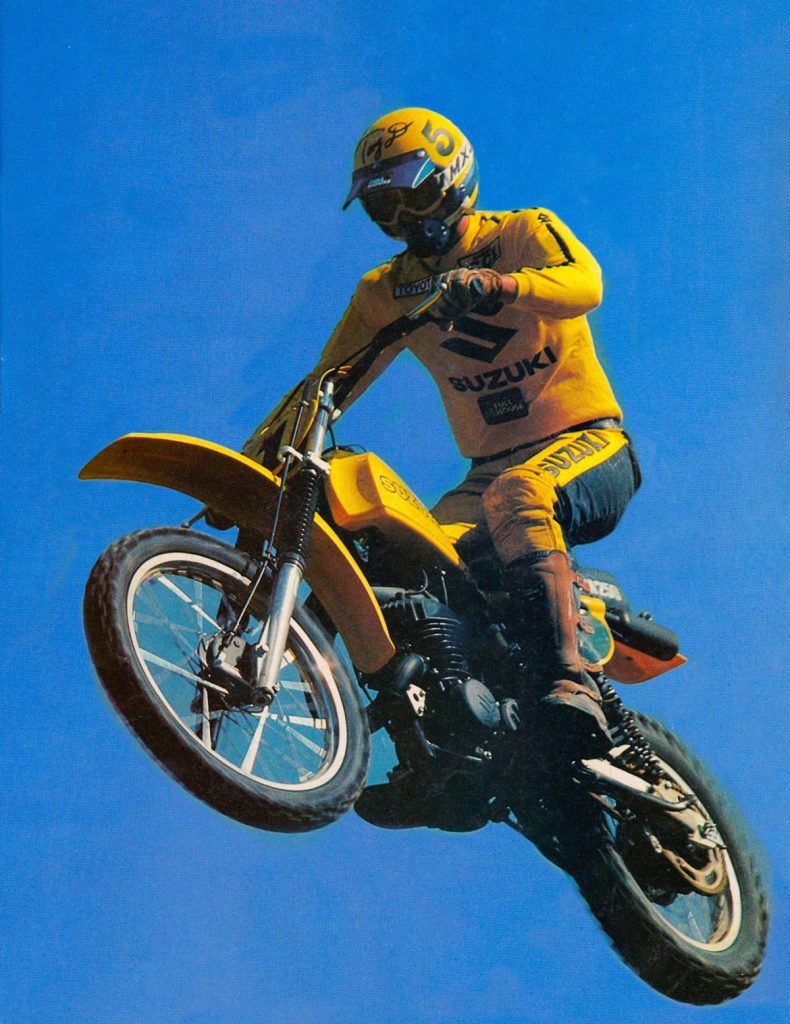

In spite of being one of the heavier bikes in the class, the RM250C-2 was a capable flyer. Tony DiStefano demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In spite of being one of the heavier bikes in the class, the RM250C-2 was a capable flyer. Tony DiStefano demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, the C2’s newly-adjustable KYB dampers provided an improved ride over the C. Under power, they were plush and well controlled, without any abnormal bottoming or weird behavior. The damping was smoother than on the C model and the shocks provided a softer feel overall. In spite of offering two adjustments for damping, the performance did not change drastically when altered. In truth, only the most sensitive of riders could even discern the difference between the hard and soft settings.

New shocks on the C-2 featured increased travel and a two-position damping adjuster. Overall performance was good for the time, but fading could become an issue in long motos. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

New shocks on the C-2 featured increased travel and a two-position damping adjuster. Overall performance was good for the time, but fading could become an issue in long motos. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the detailing end of things, the ’78 ½ RM was an improvement in some areas and a trade-off in others. The new “bone saver” front number plate featured dual extensions that wrapped around the front crossbar. This feature had been used on factory machines to prevent the front brake cable from catching on the bars and was appreciated by everyone who had ever experienced the instant nose-wheelie that resulted from this occurrence.

A new “bone saver” front number plate on the C-2 featured extensions that wrapped over the crossbar to prevent the brake cable from catching on the bars and causing a sudden and unexpected stop. Photo Credit: Mecum

A new “bone saver” front number plate on the C-2 featured extensions that wrapped over the crossbar to prevent the brake cable from catching on the bars and causing a sudden and unexpected stop. Photo Credit: Mecum

Due to the longer forks on the C-2, the new bars had to be rear-set. This made them feel cramped to some riders, but pretty much everyone appreciated the increased comfort the new rubber-mounted bar clamps provided. The new seat was also almost an inch thinner (an effort to offset the increased rear travel) and harder than on the C model. Like the bars, the new lower seat made the bike feel cramped to some and no one seemed to much like its feel.

In 1978, all of the Big Four 250 competitors were either brand new or majorly redesigned. Photo Credit: Cycle World

In 1978, all of the Big Four 250 competitors were either brand new or majorly redesigned. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Overall reliability was quite good, but some riders complained of more missed shifts than in the past. Shock fading was also an issue, with long motos resulting in a lot of hopping and swapping by the end. The shocks were also not rebuildable, so if you wanted to improve their performance, the only option was a set of aftermarket alternatives. While the new tank was more dent resistant, its mounting brackets proved fragile. Decal life was also terrible now, due to the gas fumes that quickly made their way through the plastic. At least filling the tank was easier with the new larger opening and ability to actually see the level inside.

While not the best bike in any one category, the ’78 ½ RM250C-2 offered one of the best combinations of power, handling and suspension in the class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

While not the best bike in any one category, the ’78 ½ RM250C-2 offered one of the best combinations of power, handling and suspension in the class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Overall, the 1978 ½ RM250C-2 turned out to be just what you would have expected – an improved version of the already very good RM250C. The motor was faster (if slightly harder to ride), the suspension was better, and the bodywork was more durable. It was not the most powerful (the Honda had everyone covered in that department in ‘78) and did not offer the most travel (Honda again), but it did make going fast easy, and for many riders, that is exactly what made these late-seventies RMs so appealing.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com