For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s all-new RM125N for 1979.

The seventies were a great era for Suzuki’s motocross program. At the pro level they dominated, winning countless National and Grand Prix Motocross titles during the decade. At the local level, they were just as successful with their excellent line of RM motocross machines. The RMs were light, fast, well-suspended, and ultra-competitive.

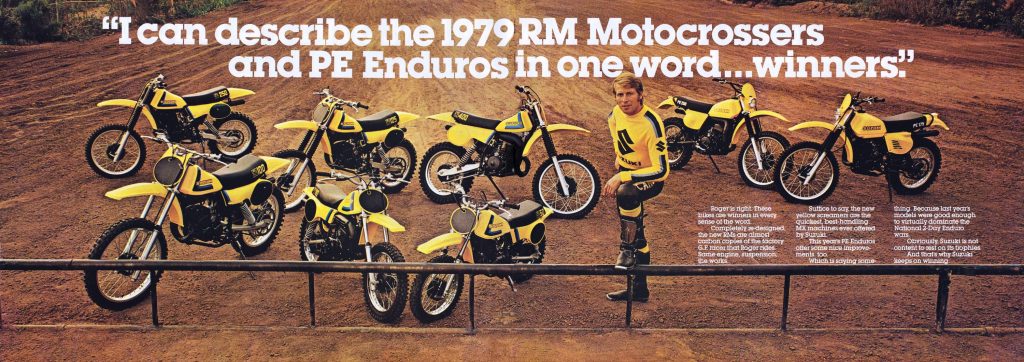

In the late seventies, Suzuki’s RM125 was one of the most successful machines in motocross. For 1979, Suzuki tried to continue those winning ways by revamping nearly everything on their eighth-liter all-star. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the late seventies, Suzuki’s RM125 was one of the most successful machines in motocross. For 1979, Suzuki tried to continue those winning ways by revamping nearly everything on their eighth-liter all-star. Photo Credit: Suzuki

During the seventies, the 125 class had risen from a bit of an afterthought to one of the most hotly-contested divisions in motocross. The arrival of the Honda CR125M Elsinore in 1974 ignited America’s desire for light, fun, and affordable racers. The Elsinore was ready to go right off the showroom floor and overnight the country’s tracks were awash in the silver and green bullets. Honda’s lead was short-lived, however. Both Yamaha’s YZ125 and Suzuki’s RM125 quickly eclipsed the Elsinore’s performance and set up a power struggle for 125 dominance that would play out through the remainder of the decade. Both Honda and Kawasaki continued to produce 125 racers, but most years they were little more than also-rans.

Today, Suzuki seems like a brand on the ropes, but in the seventies, they were a powerhouse that cranked out winners in every class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Today, Suzuki seems like a brand on the ropes, but in the seventies, they were a powerhouse that cranked out winners in every class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

All that changed in 1979 with the introduction of the most competitive lineup of 125 machines ever to grace America’s motocross tracks. After several years of mildly refreshed re-treads, Honda was back with an all-new machine that featured works styling, ultra-long-travel suspension, and buckets of bright red paint. Kawasaki was likewise back with an all-new works replica of their own, the KX125-A5. The racy new A5 promised pro-ready performance and limited-edition exclusivity to the few souls lucky enough to acquire one of the rare machines. With Yamaha providing the Suzuki’s greatest challenge in 1978, the YZ was back with a less-radical list of changes. A beefed-up frame for ’79 improved handling and new suspenders front and rear increased travel slightly. The motor also received new porting specs that looked to take the ’78 YZ’s high-rpm powerband and bring it down a bit to better compete with the class-leading RM.

In 1979, every bike in the 125 class was either all-new or majorly redesigned. Photo Credit: Motorcyclist

In 1979, every bike in the 125 class was either all-new or majorly redesigned. Photo Credit: Motorcyclist

Quack: In 1979 Suzuki saw fit to saddle all their motocross machines with this bizarre duck-billed fender design. Early-release models also had this look on the front fender as well (see photo number one above) but RMs built later in the year featured a more conventional front fender design. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Quack: In 1979 Suzuki saw fit to saddle all their motocross machines with this bizarre duck-billed fender design. Early-release models also had this look on the front fender as well (see photo number one above) but RMs built later in the year featured a more conventional front fender design. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the Suzuki side of the equation, the men from Hamamatsu were not content to sit on their laurels for 1979. With so much new competition in the class, the Suzuki engineers knew they would need to pull out all the stops to keep the RM at the head of the class in ’79. With that in mind, they scrapped 90% of their shootout-winning ‘78 machine and dialed up an all-new yellow buzz bomb for 1979. Everything was revamped, relocated, and reimagined on the new machine. All-new plastic gave the bike a fresh (if at times, controversial) look and an all-new suspension boosted travel front and rear. The motor was massaged for more power and the frame was tweaked to increase strength and improve handling. Aside from the grips and levers, this was an all-new RM.

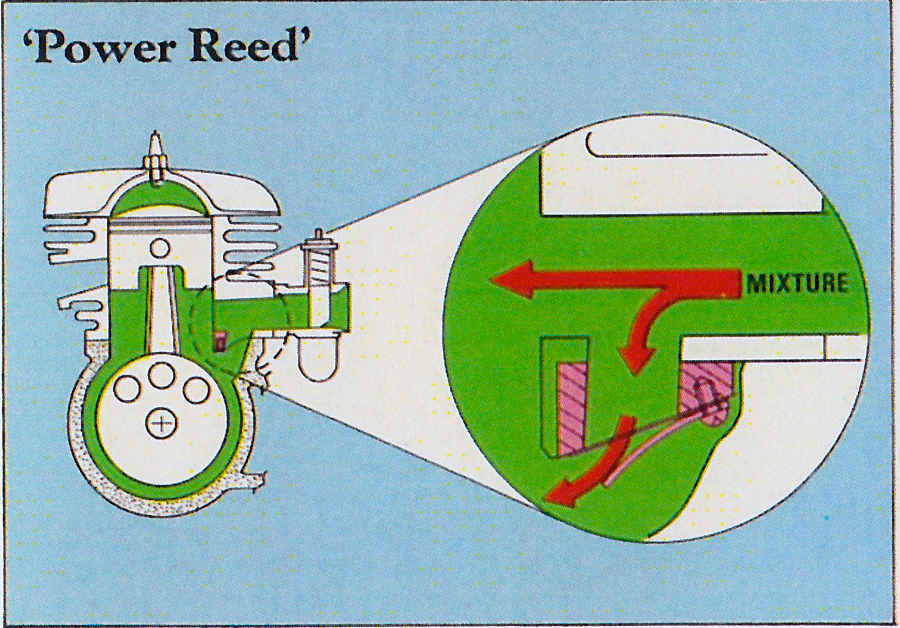

Throughout the seventies Suzuki’s two-strokes featured a unique semi-case-reed intake design they called the “Power Reed.” The theory behind the Power Reed was to combine the advantages of a case-reed and piston-port intake into one design. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Throughout the seventies Suzuki’s two-strokes featured a unique semi-case-reed intake design they called the “Power Reed.” The theory behind the Power Reed was to combine the advantages of a case-reed and piston-port intake into one design. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the chassis side, Suzuki had to make several changes to accommodate the longer travel for ’79. The new chrome-moly steel frame featured beefed up tubing and a redesigned engine cradle. The footpeg mounts were stronger for ’79 and paired with new pegs for improved control. Rake remained unchanged but the new frame offered 7mm more trail than in ’78. An all-new extruded alloy swingarm was bolted on that looked trick and promised reduced flex under heavy loads. Both wheels were new, with a full-width front hub replacing the conical design of 1978. For 1979, all the plastic was new, with a slightly larger 1.7-gallon tank replacing the 1.6-gallon unit of the year before. New FIM-mandated side plates moved the number panels rearward slightly for easier viewing and new fenders front and rear offered improved coverage and unique styling. These new heavily-valanced fenders were easily the most controversial part about the RMs styling and riders tended to love them or hate them with a passion. Early models featured this design both front and rear, with bikes shipped later in the year adopting a more traditional fender design at the front. The saddle was also new with a revised shape and a slick RM125 logo silk-screened on the sides.

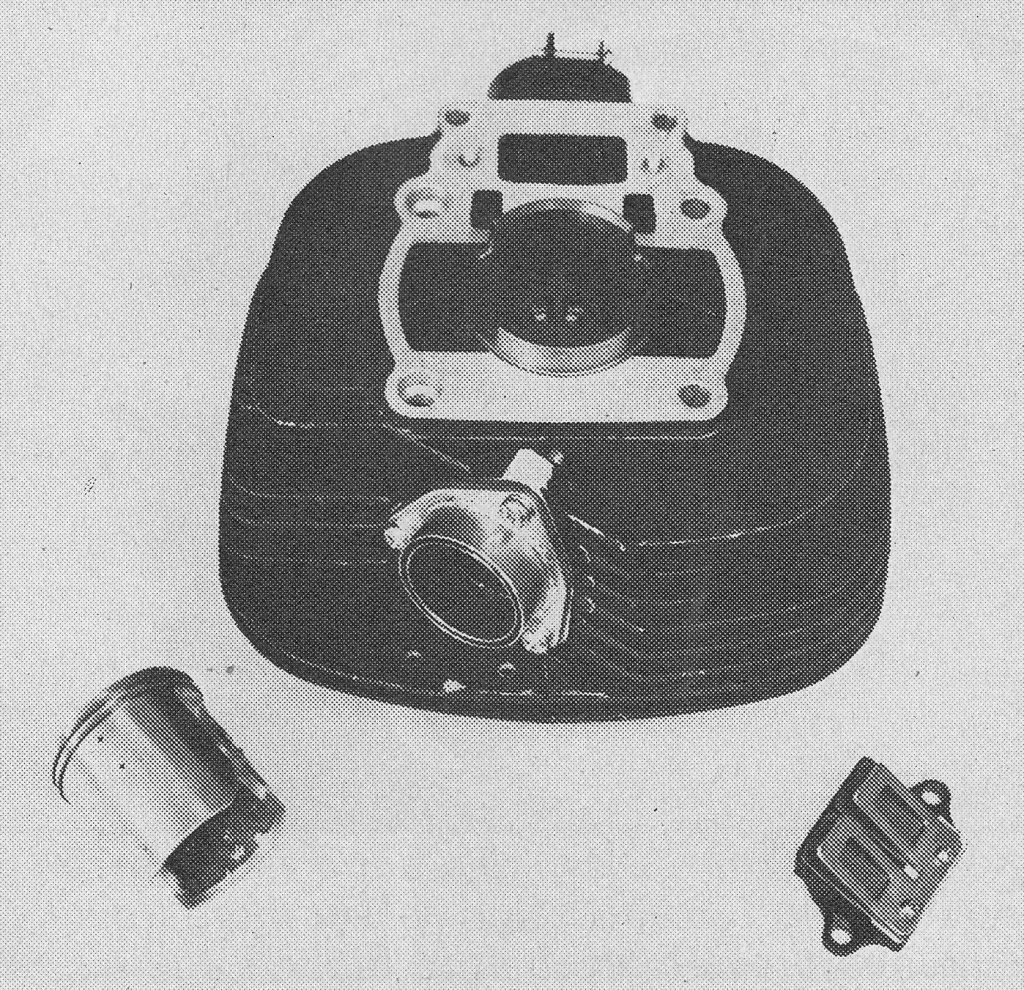

An all-new cylinder for 1979 maintained the Power Reed design of previous RMs and added new porting to boost midrange power. Photo Credit: Cycle World

An all-new cylinder for 1979 maintained the Power Reed design of previous RMs and added new porting to boost midrange power. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the motor front, Suzuki once again started from scratch for 1979. The redesigned motor maintained the 123cc displacement and 54 x 54mm bore and stroke it had employed in 1979 but added all-new porting to boost mid-range power. The new cylinder featured larger fins for increased cooling and a steel liner that allowed over-boring in the case of a seizure. This was a nice feature that the Honda (chrome) and Kawasaki (electrofusion) liners did not allow. For 1979, Suzuki did make the steel liner slightly thinner for improved heat dissipation. The new motor continued to employ the semi-case-reed “Power Reed” design Suzuki had employed on the RM125 since 1976. This design was said to offer both the low-end response of a reed-valve and the high-rpm power of a traditional piston-port arrangement. For ’79 the reed cage was slightly smaller and featured two large reed pedals instead of multiple smaller ones like in 1978.

An all-new extruded alloy swingarm for 1979 promised improved strength and added travel. In 1979, this was one of the most sano setups in moto. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

An all-new extruded alloy swingarm for 1979 promised improved strength and added travel. In 1979, this was one of the most sano setups in moto. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Feeding the motor was a new 32mm Mikuni carburetor and redesigned airbox that offered improved sealing and easier access. As in 1978, ignition duties were handed by Suzuki’s Pointless Electronic Ignition (PEI) and a single spark plug centrally located in a new head. For ’79, the head gasket thickness was increased slightly (1mm) and a new squish band was employed to improve combustion. Moving all of those spent gases out of the motor was a redesigned exhaust and silencer combination that was tuned to work with the new porting. As was common for the era, the RM’s silencer was steel and not easily rebuildable. Finishing off the motor package was a new clutch and revised six-speed transmission that raised gearing slightly across the board.

The RM’s all-new 123cc motor for 1979 ran very differently than the mill it replaced. Max output was up by two horsepower, but that peak came at a much lower point on the curve than the year before. Unlike the top-end-focused ’78, the new motor did its best work in the midrange. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The RM’s all-new 123cc motor for 1979 ran very differently than the mill it replaced. Max output was up by two horsepower, but that peak came at a much lower point on the curve than the year before. Unlike the top-end-focused ’78, the new motor did its best work in the midrange. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

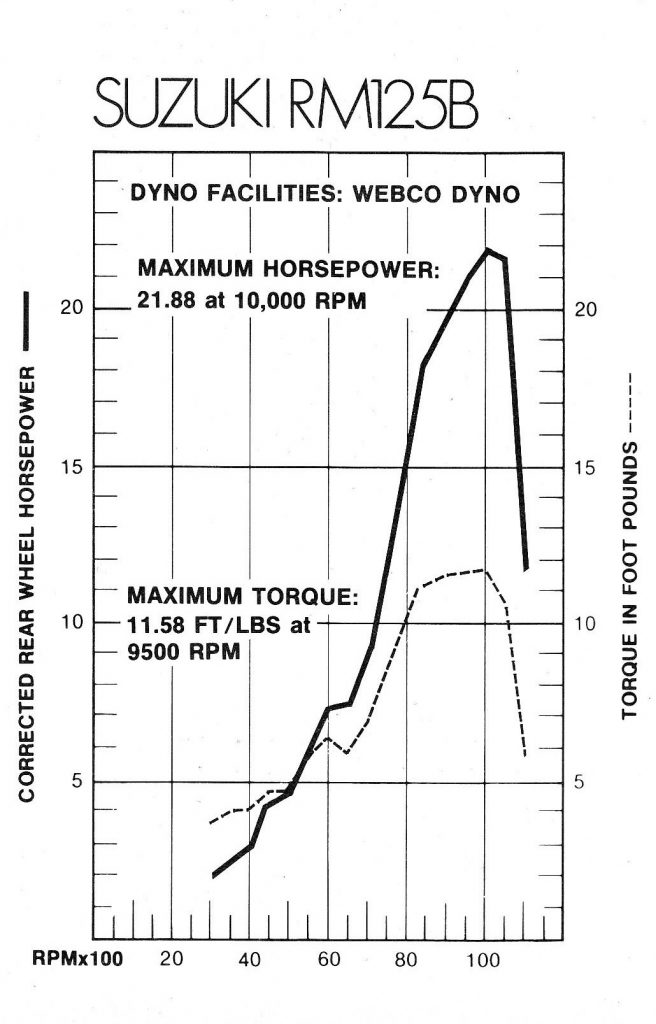

On the track, the new motor package proved to be one of the most effective available in 1979. At peak, it posted a whopping two horsepower gain over 1978 and offered an excellent midrange-focused powerband that blasted the RM out of turns and to the front. Unlike 1978, there was not a lot of top-end power available, but it was brutally effective if ridden correctly. As was typical of 125s in the pre-power valve era, there was not a lot of grunt available below the midrange, but the RM offered enough torque to get from the truck to the starting line, which was all most serious 125 pilots were looking for. For riders accustomed to the high-rpm antics of previous RM125s, the new midrange powerband took a little getting used to, but once you learned to shift a little bit earlier it was easily one of the best power packages of 1979.

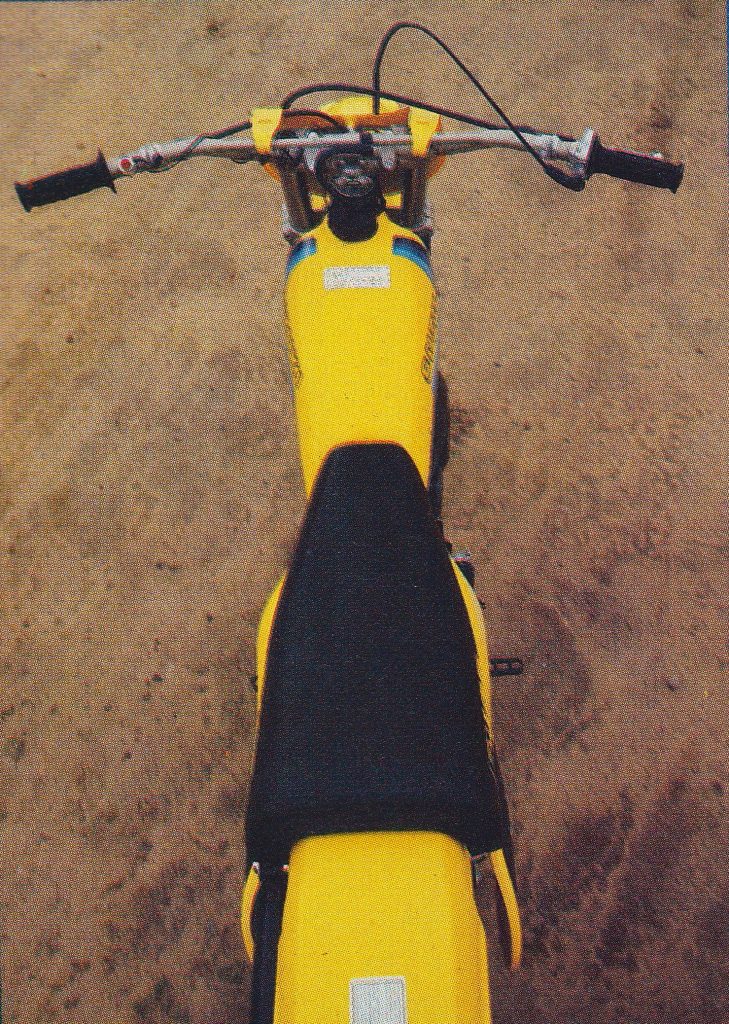

A new tank and saddle for ’79 smoothed the seat/tank junction and made the RM one of the most comfortable bikes in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

As successful as the motor changes for ’79 turned out to be, they paled in comparison to the utter domination Suzuki showed on the suspension front. Up front, Suzuki pulled out the big guns by bolting on a set of massive (for the time) 38mm KYB forks. These forks were 2mm larger than in 1978 and by far the largest-diameter units found in the 125 class. In 1979, even some 250s did not come with 38mm stanchions. In addition to being stronger, the new forks offered over 2 inches more travel than in 1978. This gave the RM the most travel in the class at a full 11.2 inches of movement. While there were no external adjustments available for damping, they did offer air caps on each fork to allow air pressure to be added or subtracted to fine-tune the ride.

All or nothing: The RM’s 21.88 horsepower does not sound like a lot by modern standards but this was near the top of the class in 1979. One look at that incredibly steep power curve is enough to give you a sense of just how peaky the powerband was on these pre-power-valved small bores. Photo Credit: Cycle World

All or nothing: The RM’s 21.88 horsepower does not sound like a lot by modern standards but this was near the top of the class in 1979. One look at that incredibly steep power curve is enough to give you a sense of just how peaky the powerband was on these pre-power-valved small bores. Photo Credit: Cycle World

With its strong burst of midrange power the RM offered one of the most effective powerbands on the track in 1979. While it lacked the YZ’s shrieking revs, it made up for it with a stronger midrange and broader overall pull. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

With its strong burst of midrange power the RM offered one of the most effective powerbands on the track in 1979. While it lacked the YZ’s shrieking revs, it made up for it with a stronger midrange and broader overall pull. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Out back, the new RM used a set of laid-down Kayaba shocks to deliver a class-leading 11.0 inches of action. This was a full 2.2 inches more than in 1978. The new shocks incorporated remote reservoirs to help reduce fading and offered two adjustable settings for damping performance. To change the settings, the shocks had to be removed and partially disassembled, but at least there was some level of adjustment offered. One other nice feature added to the RM’s Kayaba dampers for ’79 was a set of rubber bumpers at the base of the shock shaft. This was done both to protect the shock bodies and lessen the metal-to-metal clank when bottoming out.

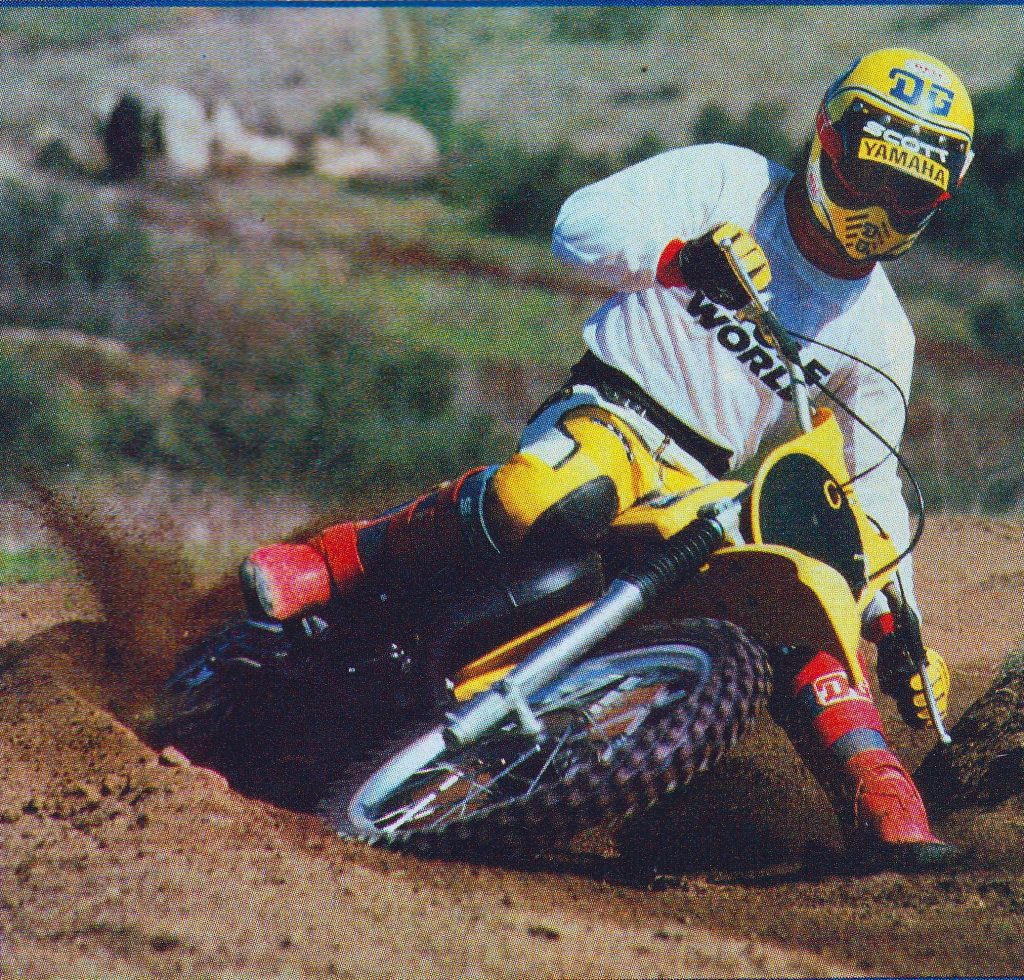

The one area where the RM lagged behind most of its competition was in the turning department. Pro riders like Cycle World’s Steve Bauer could make the RM turn but it took more effort than machines like the KX and YZ. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The one area where the RM lagged behind most of its competition was in the turning department. Pro riders like Cycle World’s Steve Bauer could make the RM turn but it took more effort than machines like the KX and YZ. Photo Credit: Cycle World

This is what passed for fork adjustment in the 1970s. These Schrader valves attached to the top of each fork allowed air to be added or subtracted to fine-tune the ride. Unlike modern air forks, this pneumatic assist was designed as a supplement to the coil springs and not a replacement for them. Photo Credit: Suzuki

This is what passed for fork adjustment in the 1970s. These Schrader valves attached to the top of each fork allowed air to be added or subtracted to fine-tune the ride. Unlike modern air forks, this pneumatic assist was designed as a supplement to the coil springs and not a replacement for them. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1979, the RM’s 38mm Kayaba forks offered the best performance in the class by a wide margin. With their beefy stanchions and a whopping 11.2-inches of travel, they featured both the longest travel and the most flex-free performance available at the time. Riders of every skill level praised their smooth and well-controlled action. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1979, the RM’s 38mm Kayaba forks offered the best performance in the class by a wide margin. With their beefy stanchions and a whopping 11.2-inches of travel, they featured both the longest travel and the most flex-free performance available at the time. Riders of every skill level praised their smooth and well-controlled action. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Out in the real world of jumps, whoops, and ruts, the RM delivered by far the best ride in the class. The RM’s long-travel forks provided a plush ride that none of its competitors could match. The beefy 38mm sliders gave the front end a more precise feel in the rough and kept flex to a minimum on hard hits. Only the RM was capable of handling big whoops and gobbling up brake chop with equal ease. Really fast guys might have wanted stiffer springs but for most riders, a tweak of the oil and air settings was all that was needed to dial in the RM’s front end to near perfection.

As with the forks, the RM’s dual Kayaba dampers offered both the most travel and best ride in the class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

As with the forks, the RM’s dual Kayaba dampers offered both the most travel and best ride in the class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the rear, the RM’s KYB shocks were once again king of the class. They offered an ultra-plush ride on small hits and a sufficient level of control on large G-outs. Although there were two damping settings available, there did not seem to be much perceptible difference between them on the track. With either setting engaged, the RM’s dampers gobbled up bumps and sharp hits far better than any other machines in the class. With its remote reservoirs, there was also none of the fade seen on Honda and Yamaha rear ends. About the only real complaint riders had with the rear end was the fact that the shocks could not be rebuilt and had to be replaced once they started to wear out.

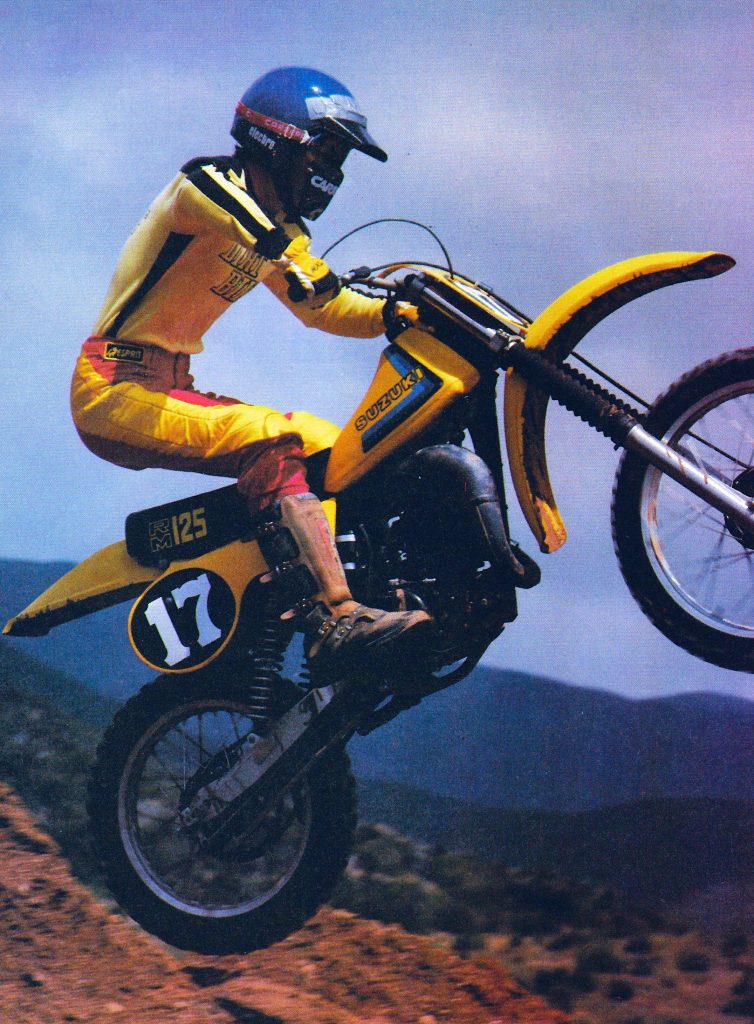

Airtime was no worry on Suzuki’s silky-smooth RM in 1979. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Airtime was no worry on Suzuki’s silky-smooth RM in 1979. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the handling front, the ’79 RM125 was not the shredder we would come to associate with Suzukis in later years. Steering precision was decent but some riders complained about the tall stance hindering steering feel. Shorter bikes like the YZ offered a more “hunkered down” feel in the turns that riders of the time had become more accustomed to. Of course, all of these bikes would feel small today, but riders in 1979 were not yet used to machines with skyscraper seat heights and ultra-long-travel suspension. Compared to the competition, the RM offered only mediocre turning, but it did feature rock-solid stability. Its supple suspension made the bike far less of a handful in the rough and that advantage was only amplified as the speeds increased. If you were planning on pinning it through the Southwick sand, then the RM was your machine.

Weird fender aside, the rest of the RM125 was a handsome machine. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Weird fender aside, the rest of the RM125 was a handsome machine. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While most riders liked the new flatter bar bend for 1979 there was less praise for the RM’s stock throttle. The grip was too short for large hands and the flexy cable and housing provided an imprecise feel. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While most riders liked the new flatter bar bend for 1979 there was less praise for the RM’s stock throttle. The grip was too short for large hands and the flexy cable and housing provided an imprecise feel. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the detailing front, the new RM was mostly well-regarded for its time. Nearly everyone loved the new shape of the tank but abhorred the oddball shape of the rear fender. At least most people who bought an RM in ’79 got the more attractive redesigned front one instead of the weird duckbill it came with initially. The new FIM side plates looked sano but refused to stay on for any length of time. For some reason, the bolts holding them on absolutely refused to stay tight and pretty much every magazine test mentioned having to rig up some manner of keeping them from falling off mid-moto. The stock bars were butter-soft and prone to whacking taller riders in the knee in turns. This was not appreciated. The stock decals were even less durable than the wet-noodle bars and most lasted about an afternoon before they read “uzuki”, “uki”, or some other indecipherable variation thereof. To reduce the drag on the motor, Suzuki’s engineers saw fit to mount a flimsy 428 chain on the RM. This chain was, unfortunately, barely suitable for a mini. It stretched, broke, and ejected circlips at an alarming rate. Most savvy racers upgraded to a 520 in short order. Last of the major gripes was the RM’s stock throttle which featured a grip so short that many rider’s hands hung over the end of it. The cable was also garbage and flexed heavily when the throttle was applied quickly. Once again, most smart riders quickly ash-canned this for an aftermarket unit.

Fast, well suspended, and just a bit quirky, Suzuki’s RM125 was the king of the 125 class in the late seventies. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Fast, well suspended, and just a bit quirky, Suzuki’s RM125 was the king of the 125 class in the late seventies. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the plus side for 1979 were the RM’s powerful motor, supple suspension, excellent stability, and proven track record of winning. It was not a perfect 125 racer, but in 1979, it was as close as you were going to get to the ultimate tiddler class weapon. In 125 pro racing at the time, there was a reason most every privateer rode a Suzuki. For nearly a decade, the RM was the dominant machine in 125 racing and in 1979 Suzuki upheld that tradition by delivering a knockout punch to the most competitive field of 125 racers the sport had ever seen.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com