For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the machine that heralded Suzuki’s return to the high-performance off-road market, the all-new 1989 RMX250.

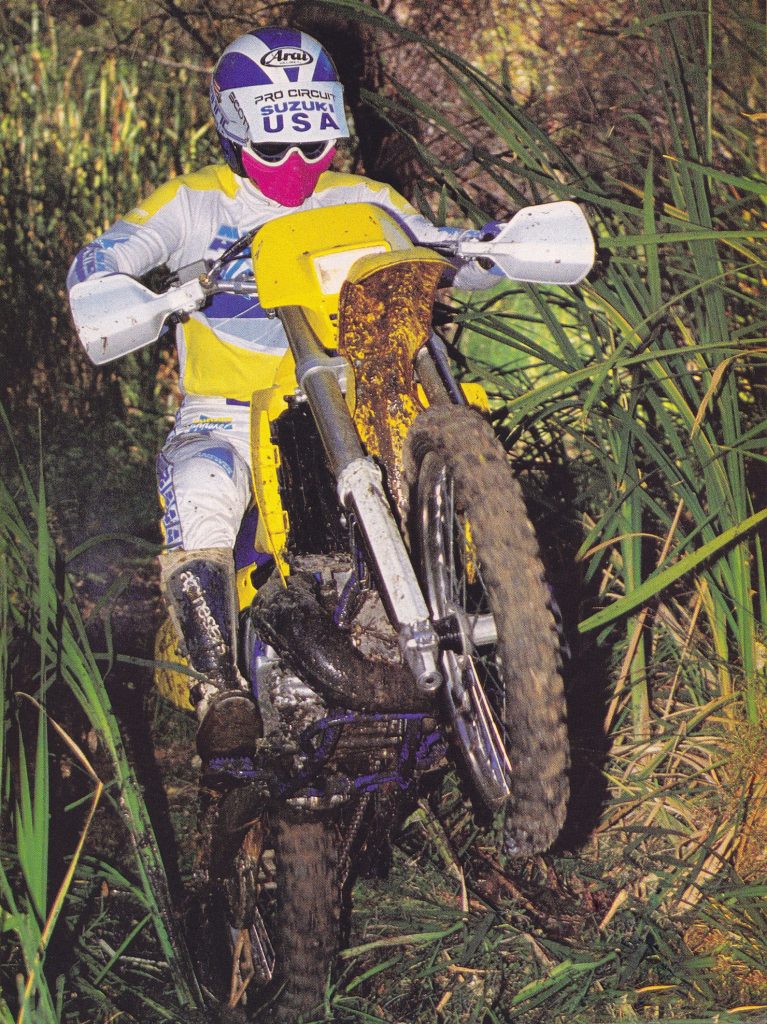

After half a decade on the sidelines, Suzuki jumped back into the performance Enduro game with their all-new RMX250 in 1989. Based on the all-new ’89 RM250, the RMX came ready for the trail with EPA certification and a full complement of Enduro hardware. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After half a decade on the sidelines, Suzuki jumped back into the performance Enduro game with their all-new RMX250 in 1989. Based on the all-new ’89 RM250, the RMX came ready for the trail with EPA certification and a full complement of Enduro hardware. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The Japanese have always had an interesting relationship with the off-road racing market. While motocross machines like the YZ, CR/CRF, RM/RM-Z, and KX have continued to be mainstays of the Japanese performance lineups, Enduro racers like the IT, MR, PE, and KDX have come and gone over time. While the Europeans have steadfastly stuck to the hard-core off-road market, the Japanese have shown far less dedication to this passionate segment of the motorcycling community.

Before the introduction of the RMX, Suzuki’s performance off-road entry had been their line of PE (Pure Enduro) machines. Initially, the PEs were decent performers but a lack of development and overall neglect by Suzuki would lead to their retirement in 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Before the introduction of the RMX, Suzuki’s performance off-road entry had been their line of PE (Pure Enduro) machines. Initially, the PEs were decent performers but a lack of development and overall neglect by Suzuki would lead to their retirement in 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

At the start of the 1980s, all of the Big Four Japanese manufactures had 250cc machines aimed at the Enduro market. The IT, PE, KDX, and XR 250s offered civility, refinement, and typically, a watered-down version of the technology found on their motocross cousins. Eventually, however, the Japanese seemed to lose interest in this market and by 1985 only Honda’s mild-mannered XR250R remained to do battle with the European thoroughbreds. While the XR was super fun, it was far too heavy and underpowered to compete without serious modifications. It was a great play bike, but not much of a true racer.

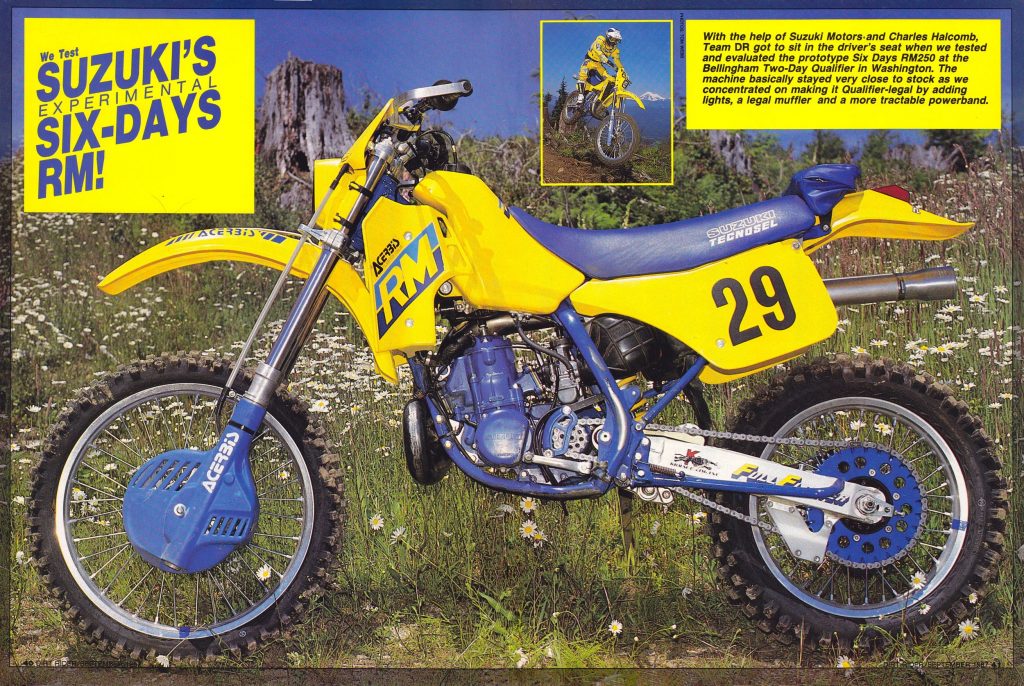

After a few years out of off-road racing Suzuki got the itch again in 1986 and hired ISDE veteran Charles Halcomb to help them develop a new off-road racer. Early prototypes like this converted ’87 RM250 showed Suzuki was interested in producing a more serious machine than the earlier PEs had been. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

After a few years out of off-road racing Suzuki got the itch again in 1986 and hired ISDE veteran Charles Halcomb to help them develop a new off-road racer. Early prototypes like this converted ’87 RM250 showed Suzuki was interested in producing a more serious machine than the earlier PEs had been. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

By 1986, Suzuki began to once again get the itch to try and compete in the Enduro market. Their PE line had been discontinued in 1984 and their DR line of four-strokes was even less serious than Honda’s XRs. At the time, Suzuki was trying to revitalize their motocross program after several years of disappointing results. The production RMs were no longer the class leaders they had been throughout the seventies and early eighties and most people acknowledged the yellow team needed new blood and new ideas.

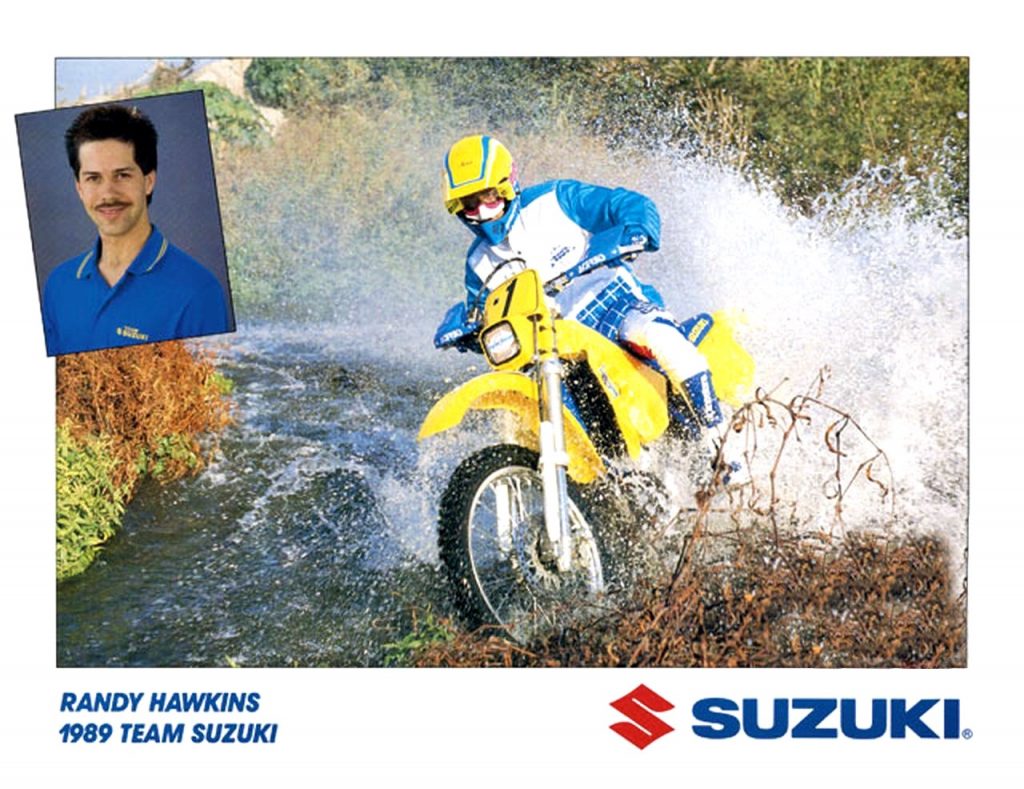

After sticking their toe into the off-road waters in 1987, Suzuki jumped in with both feet in 1988. Racing a converted RM250, a relatively unknown rider from Travelers Rest, SC by the name of Randy Hawkins took Suzuki to its first AMA Enduro championship. The win not only signaled Suzuki’s seriousness about the off-road racing market, but it also ended several-decades-long domination of Enduro racing by the Europeans. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

After sticking their toe into the off-road waters in 1987, Suzuki jumped in with both feet in 1988. Racing a converted RM250, a relatively unknown rider from Travelers Rest, SC by the name of Randy Hawkins took Suzuki to its first AMA Enduro championship. The win not only signaled Suzuki’s seriousness about the off-road racing market, but it also ended several-decades-long domination of Enduro racing by the Europeans. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

On the motocross side, Suzuki hired multi-time AMA champion Bob Hannah to help whip the RMs back into competitive form, and on the off-road side, Suzuki hired ISDE competitor Charles Halcomb away from Husqvarna to help them develop an all-new Enduro machine. Initially, this new project was a pure skunkworks operation, with Halcomb compiling a list of wants for a competitive off-road racer. By this point, it had been many years since the Japanese had truly gone all-out in an effort to compete with the Europeans on their own turf. Husqvarna and KTM were no longer motocross powers in the US, but they remained the dominant forces in off-road racing. For Suzuki to go head-to-head with the Europeans, it would take a far more serious effort than they had shown in the past.

For 1989, Suzuki unveiled a sexy all-new RM250 that would serve as the underpinning for the production RMX. Unlike previous Suzuki off-road offerings, the new RMX would get all the most up-to-date technology and components from the motocross development team. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For 1989, Suzuki unveiled a sexy all-new RM250 that would serve as the underpinning for the production RMX. Unlike previous Suzuki off-road offerings, the new RMX would get all the most up-to-date technology and components from the motocross development team. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the Japanese side, most previous off-road machines had been poor cousins of their motocross brethren. Unlike the Europeans, who equipped their off-roaders with all the latest in MX technology, most Japanese Enduro bikes featured chassis and components that looked the part but were inferior in quality and construction. Mild-steel frames, low-tech suspension, and low-power motors were more often than not the Japanese approach in the Enduro class.

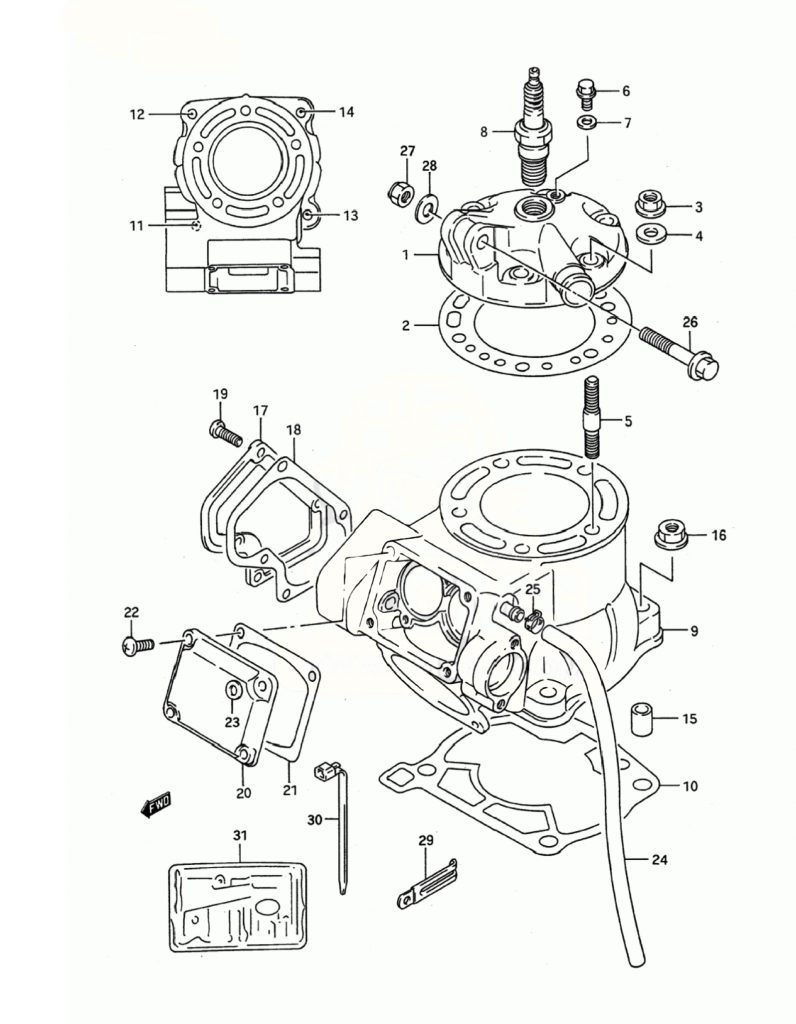

Both the RM and RMX shared the same cylinder and head but there were several changes to the top end aimed at meeting EPA guidelines, increasing durability, and fine-tuning performance for off-road conditions.

Both the RM and RMX shared the same cylinder and head but there were several changes to the top end aimed at meeting EPA guidelines, increasing durability, and fine-tuning performance for off-road conditions.

For his new top-secret racer, Halcomb’s wish list included a bike with motocross performance and off-road versatility. For years, serious racers had been doing just that by converting their RMs, CRs, KXs, and YZs to off-road use by installing heavy flywheels, bolting on skid plates, swapping tanks, and slipping on spark-arrested silencers. This do-it-yourself approach was effective but costly and time-consuming.

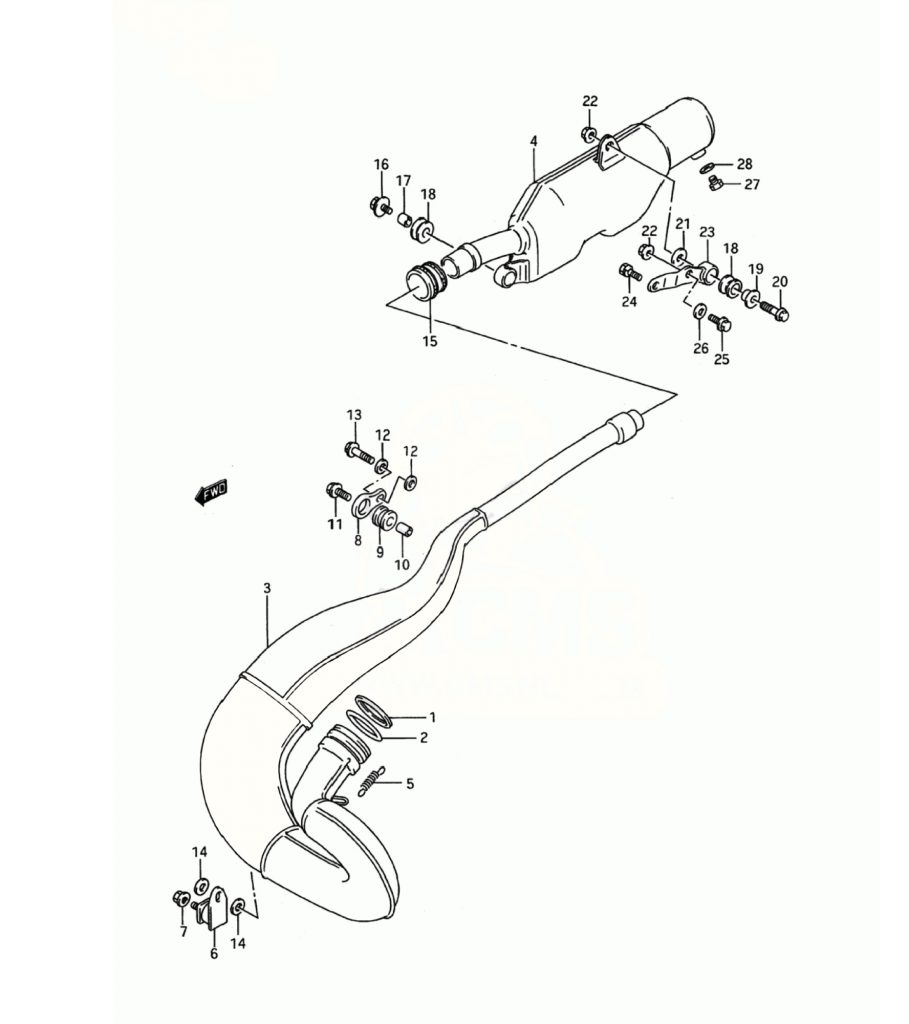

Boat Anchor: According to Suzuki, the RMX’s pipe shared the same internal dimensions as the motocross version but a double-walled construction reduced noise (and upped weight) considerably. US-bound RMXs also featured a massive steel muffler that was closer to something found on one of their ATVs than anything seen on a typical motocross track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Boat Anchor: According to Suzuki, the RMX’s pipe shared the same internal dimensions as the motocross version but a double-walled construction reduced noise (and upped weight) considerably. US-bound RMXs also featured a massive steel muffler that was closer to something found on one of their ATVs than anything seen on a typical motocross track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For the new machine, Halcomb wanted that work to already be done at the factory. He envisioned a machine based on a motocross model, in the European mold, with all the Enduro hardware already installed. That meant a versatile wide-ratio transmission, standard lighting (a requirement for Enduro racing), off-road specific suspension settings (installed in MX-quality components), a larger tank, and protection for all the bike’s vulnerable bits.

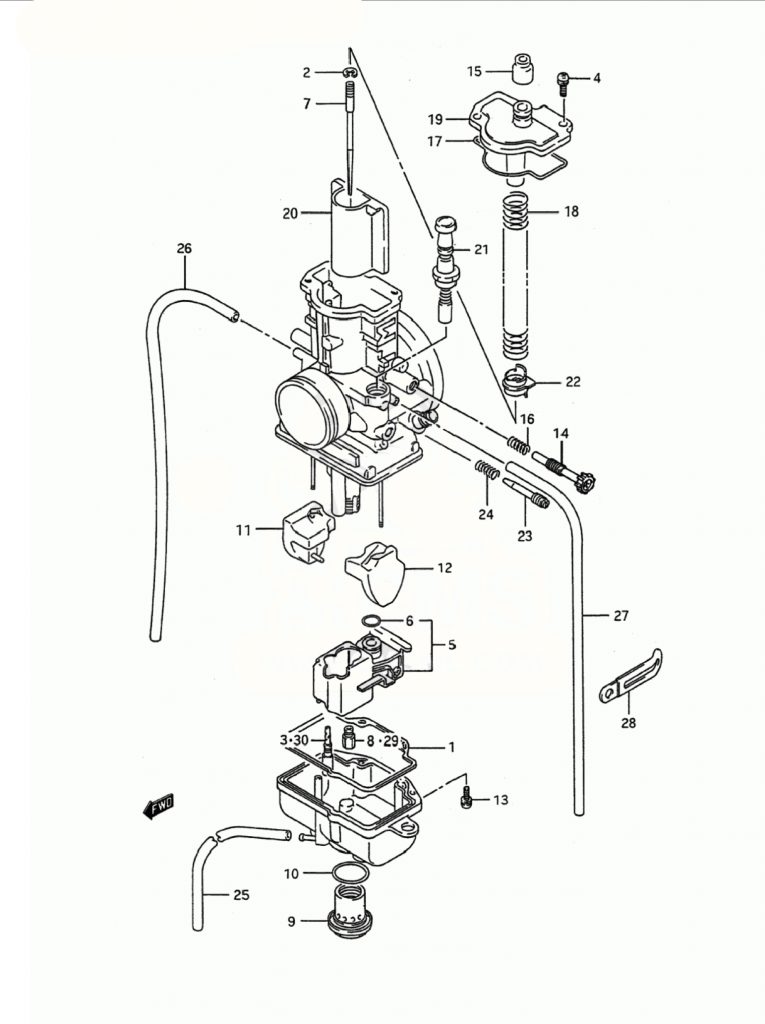

The RMX featured the same Mikuni 38mm “Slingshot” carburetor found on the motocross models but a throttle-stop added to the top of the carburetor prevented the slide from opening fully in stock condition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RMX featured the same Mikuni 38mm “Slingshot” carburetor found on the motocross models but a throttle-stop added to the top of the carburetor prevented the slide from opening fully in stock condition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1987, Halcomb cobbled together just such a machine and let Dirt Rider magazine test it in their September 1987 issue. The bike was based on the much-improved ’87 RM250 and featured only the minimum amount of modification to make it off-road ready. It was presented as a “proof of concept” idea for the brand and was well-received by the magazine editors who were enthusiastic for the Japanese to get back in the off-road game. At this point, the plans for Halcomb’s brainchild were still very much up in the air but the wheels at Suzuki were turning.

Both the RM and RMX shared an all-new chromoly steel frame and redesigned Full Floater linkage in 1989. Photo Credit Suzuki

Both the RM and RMX shared an all-new chromoly steel frame and redesigned Full Floater linkage in 1989. Photo Credit Suzuki

Back in Japan, the engineers already had most of the development done on a radical new RM250 slated for the 1989 season. The new machine ditched the dated looks of the current RM in favor of sleek lines and cutting-edge performance. The redesigned bike was slated to introduce Suzuki’s first inverted fork design and move to a 125-style case-reed intake system. This new machine would also provide the underpinning for Suzuki’s most ambitious off-road racer to date, the all-new RMX.

Standard crash bars added to the frame provided additional engine protection on the RMX. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

Standard crash bars added to the frame provided additional engine protection on the RMX. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

While Halcomb and his team were busy locking down the performance targets for the RMX, the Suzuki legal and marketing divisions were busy dealing with the demands of their dealers and Uncle Sam. When they had surveyed their dealers, Suzuki had found that their partners wanted any new off-road machine to be EPA-legal. That meant the bike would be legal to ride in parks and on government land like Honda’s hugely popular XRs. While this would make the machine an easier sell for dealers, it would pose challenges for Suzuki’s engineers in Japan. If the RMX was not going to be sold as a “closed course” competition machine then it was going to have to meet stringent sound and emission requirements set forth by the US government; requirements that were likely going to do quite a bit to neuter the RMX’s motocross-bred performance.

Handguards, a front disc cover, a larger tank, an O-ring chain, and full lighting made the RMX trail-ready right out of the crate. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

Handguards, a front disc cover, a larger tank, an O-ring chain, and full lighting made the RMX trail-ready right out of the crate. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

Being based on the all-new 1989 RM250, the RMX shared 90% of its DNA with the motocross model, but that extra 10% made a significant difference in its performance. Both machines shared an all-new chromoly steel frame and redesigned Full Floater single-shock rear suspension system but the RMX frame featured crash bars under the motor for additional protection. The rear shock featured off-road specific settings and zerks on the linkage to simplify maintenance. The RMX also shared the RM’s new 41mm Kayaba inverted fork but the Enduro version employed a different piston and softer setting to provide a more compliant ride for off-road use. Both machines featured all-new bodywork that was a huge improvement over previous Suzuki styling efforts. The front fender no longer looked like a duckbilled platypus and the overall styling was sleek instead of agricultural. Both machines shared the same front fender, shrouds, and side plates, but the RMX featured a larger rear fender (with a taillight), an 18-inch rear wheel (the RM received a 19-inch hoop in ’89), quick-release axles, handguards, an odometer, a side stand, a larger tank (by 0.7-gallon), a different saddle (designed to work with the larger tank), an O-ring chain, and a headlight in place of the RM’s front number plate.

Charles Halcomb played a huge role in the development of the new RMX250. While the stock machine may not have been the no-compromise racer he initially envisioned, the DNA was there to turn the RMX into a national-caliber contender. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

Charles Halcomb played a huge role in the development of the new RMX250. While the stock machine may not have been the no-compromise racer he initially envisioned, the DNA was there to turn the RMX into a national-caliber contender. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

On the motor side, the RMX featured a modified version of the same all-new water-cooled, case-reed induction 249.6cc mill as the RM250. Both motors offered five speeds and a manual clutch, but the RMX employed off-road specific ratios designed to increase its versatility. Both the cylinder and head were identical to the RM’s, but the RMX featured a two-ring piston (the RM only used a single ring) and a thicker head gasket. Unfortunately, most of the other motor differences were aimed at appeasing the EPA rather than improving performance.

In 1989, the two-stroke Enduro class was full of an assortment of very diverse offerings ranging from mild to wild. Of the five pictured here, only the RMX and KDX were EPA legal in stock condition but both paid a price in performance for their stealthiness. At the other end of the spectrum was the completely uncorked YZ250WR, which offered motocross performance in a do-it-yourself off-road package. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1989, the two-stroke Enduro class was full of an assortment of very diverse offerings ranging from mild to wild. Of the five pictured here, only the RMX and KDX were EPA legal in stock condition but both paid a price in performance for their stealthiness. At the other end of the spectrum was the completely uncorked YZ250WR, which offered motocross performance in a do-it-yourself off-road package. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

To be EPA legal, the RMX would need to pass a very stringent 82 decibel sound limit. Of the RMX’s competitors, only the Honda XR250R and new Kawasaki KDX200 were able to pass this bar for certification in 1989. None of the European Enduro machines were even close to being this silent and the new YZ250WR did not even bother to try with its YZ-spec silencer and running gear. All of those machines were “closed course only” and illegal for riding on most public land. By going for EPA certification, Suzuki opened up its riding options but closed off a great deal of its performance envelope.

Inverted forks were all the rage in the late eighties and the RMX received a version of the all-new 41mm Kayaba units found on the RM250 for 1989. While the rigidity benefits of the inverted design were less clear off-road, the reduction in under-hang below the axle they provided was appreciated in the deep ruts and rocks common in the woods. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

Inverted forks were all the rage in the late eighties and the RMX received a version of the all-new 41mm Kayaba units found on the RM250 for 1989. While the rigidity benefits of the inverted design were less clear off-road, the reduction in under-hang below the axle they provided was appreciated in the deep ruts and rocks common in the woods. Photo Credit: Jeff Weir

In the end, the new RMX met its EPA target, which pleased the dealers and made the bike one of the most versatile off-road offerings available in ’89. If left stock, it was whisper-quiet and legal to be ridden in places that would have gotten your YZWR impounded. It was no more obnoxious than a Yamaha Blaster and happy to putter around all day as a proper trail machine should. If you were looking for RM-level performance though, you were sure to be badly disappointed.

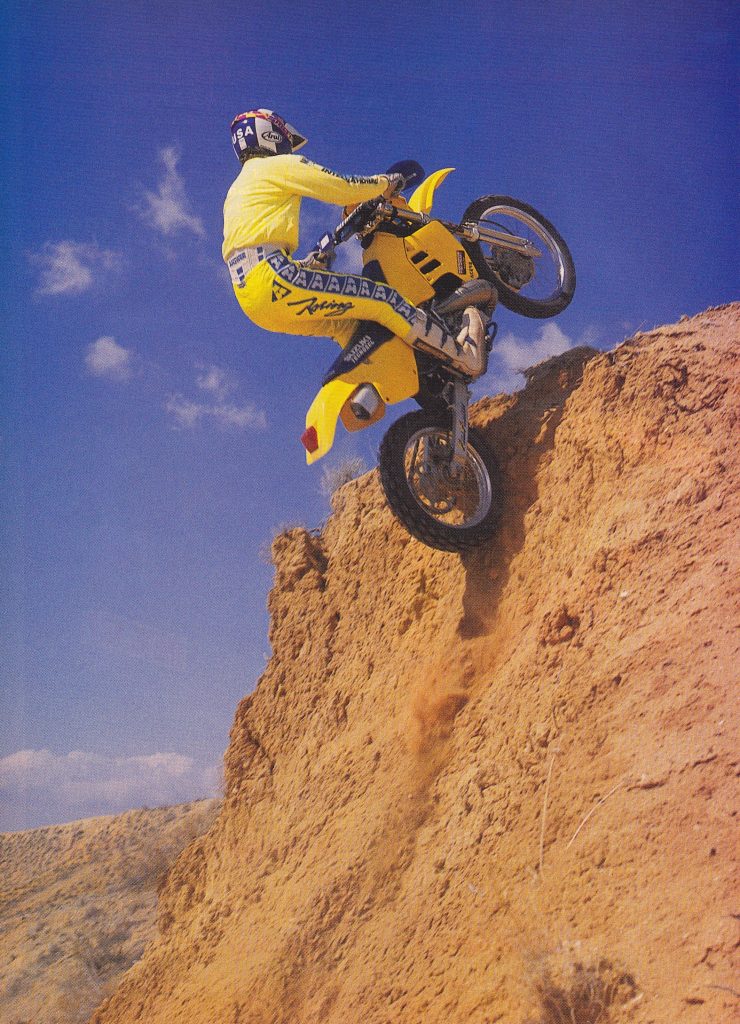

Once uncorked, the RMX250 was capable of climbing any ascent the pilot was willing to attempt. Here Robb Mesecher demonstrates the RMX’s Spiderman capabilities. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Once uncorked, the RMX250 was capable of climbing any ascent the pilot was willing to attempt. Here Robb Mesecher demonstrates the RMX’s Spiderman capabilities. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

To meet their sound goals, the Japanese engineers had made several compromises that limited the RMX’s performance. While both the RM and RMX shared the same 38mm Mikuni “Slingshot” carburetor, the X version featured a different top that prevented the slide from opening fully. There was also a limiter installed in the power-valve mechanism and an extremely restrictive lid mounted to the top of the airbox. To further reduce sound, the exhaust pipe used a dual-walled construction (with the same internal dimensions as the RM according to Suzuki) and the massive steel silencer featured an internal spark arrestor and choked-off outlet.

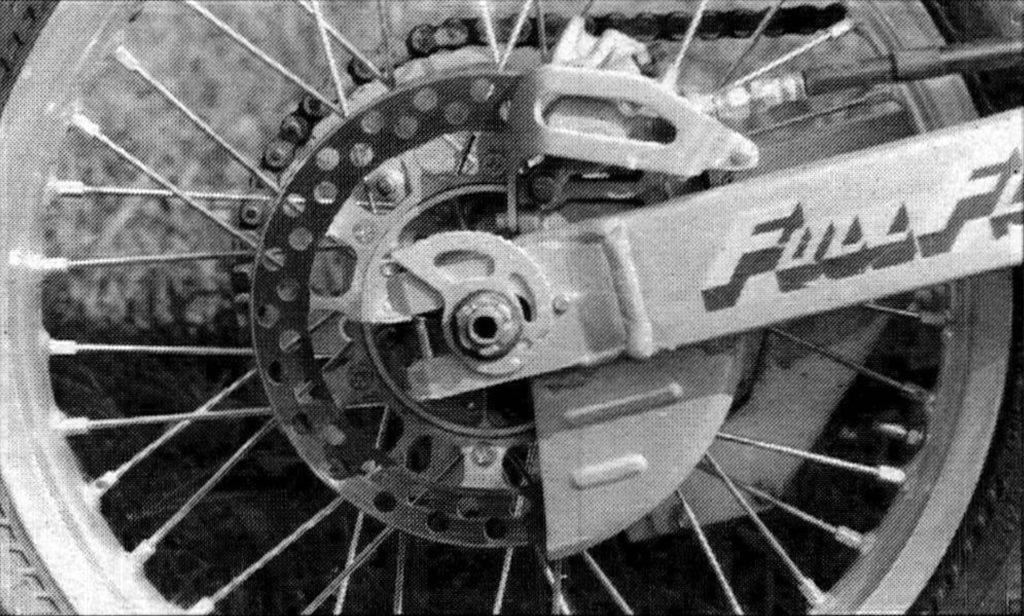

Trail-friendly features like a quick-release rear wheel and quick-pull front axle made trail-side repairs fast and easy. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Trail-friendly features like a quick-release rear wheel and quick-pull front axle made trail-side repairs fast and easy. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

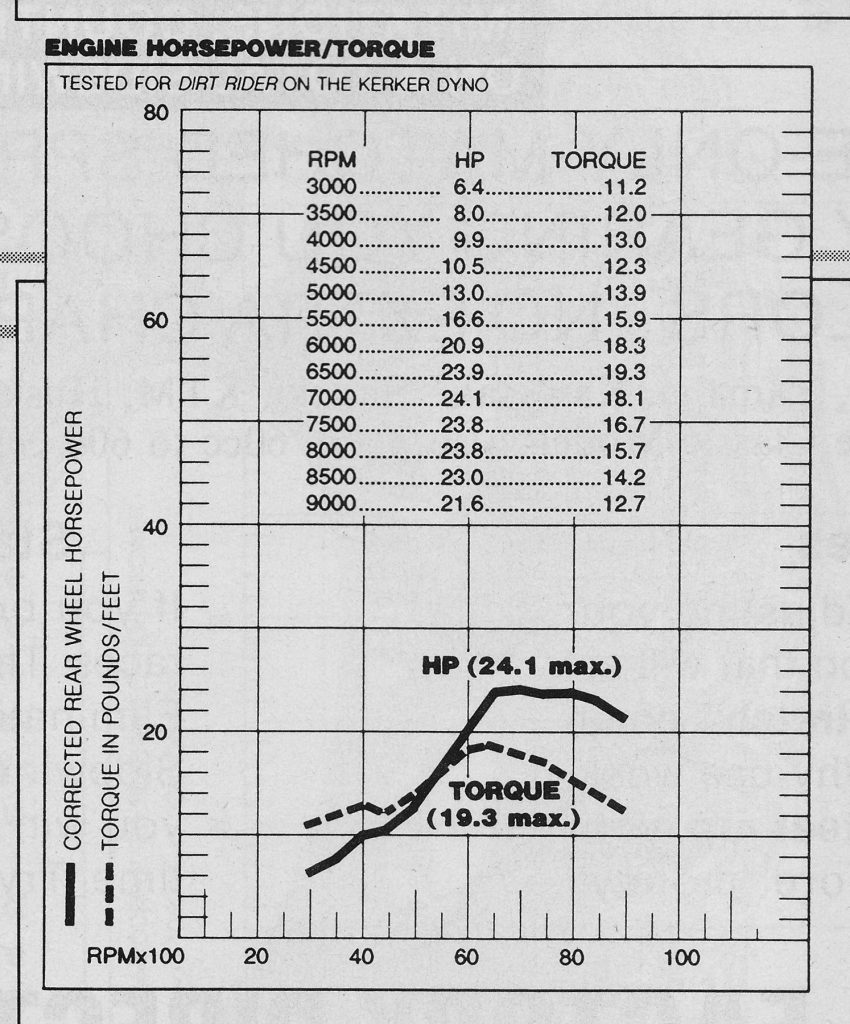

On the trail, all of these restrictions added up to a 250 with the power of a poor-running 125. On Kerker’s dyno, the stock 1989 RMX250 pumped out 24.1 horsepower and 19.1 foot-pounds of torque. This was more torque but three less horsepower than the stock Honda CR125R put out on the same dyno in 1989. The stock RMX’s output could not even best the equally stealthy KDX200 with its 28.3 fire-breathing horses. In stock condition, the bike was quiet, but incredibly choked off and underpowered. Low-end power was anemic, and the bike demanded to be revved to make any sort of usable power. Steep hills, deep sand, and muddy going easily bogged down its modest output. With the restrictions in place, the only way to go fast was to ride it like a 125; pinning it to the throttle stop and using momentum to keep the fun going. Make a mistake and let it fall off the pipe and you were probably going to need a downshift (or two) and a great deal of clutch abuse to get the X back up to speed.

Corked: In stock condition, the new RMX250 produced a paltry 24.1 horsepower on Kerker’s dyno when Dirt Rider tested it in 1989. That was less than every 125 available that year and even less than Kawasaki’s equally choked-off new KDX200. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Corked: In stock condition, the new RMX250 produced a paltry 24.1 horsepower on Kerker’s dyno when Dirt Rider tested it in 1989. That was less than every 125 available that year and even less than Kawasaki’s equally choked-off new KDX200. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With all the restrictors in place, the ‘89 RMX250 produced a narrow 125-style of power. There was very little bottom, and the bike needed to be revved mercilessly to keep up any sort of decent pace on the trail. Once the EPA stuff was removed the powerband improved greatly but the bike still preferred to be revved rather than chugged. Photo Credit: Suzuki

With all the restrictors in place, the ‘89 RMX250 produced a narrow 125-style of power. There was very little bottom, and the bike needed to be revved mercilessly to keep up any sort of decent pace on the trail. Once the EPA stuff was removed the powerband improved greatly but the bike still preferred to be revved rather than chugged. Photo Credit: Suzuki

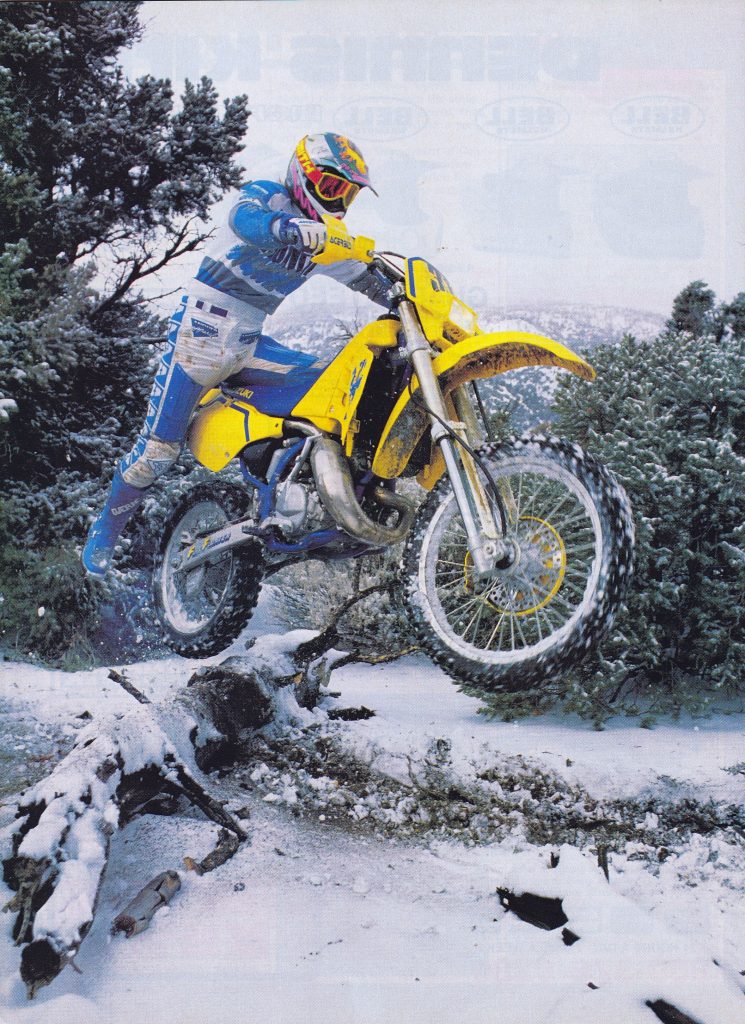

Thankfully though, getting more power out of the RMX was a relatively simple process. Because the basic DNA was mostly RM, all you had to do was swap some parts to bring the Zook’s powerband to life. By removing the airbox cover and swapping the carb top, power valve covers, pipe, and silencer for RM units the RMX was completely transformed. If you wanted even more performance, you could also replace the RMX’s head gasket with the thinner unit from the RM. With these simple mods in place, the RMX’s output jumped an eye-opening 10 horsepower. This put it on par with most of the stock Europeans but still well behind the 40-horsepower produced by the fully uncorked YZWR.

With a few RM parts installed the RMX became the ultimate play bike/racer. Here “Radical” Rich Taylor demonstrates the RMX’s all-weather capabilities. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With a few RM parts installed the RMX became the ultimate play bike/racer. Here “Radical” Rich Taylor demonstrates the RMX’s all-weather capabilities. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Once freed of its government-mandated encumbrances, the RMX provided a very competitive Enduro powerband. Even uncorked, it was no tractor and the RMX made most of its usable power relatively high in the power curve. With its heavy flywheel, the bike could be lugged without concern of stalling, but there was not a ton of grunt on hand to blast over a fallen tree or through a deep bog. Keep it singing and the RMX could keep up with anyone but try and ride it like a big-bore and you were going to lose time before the next check.

Excellent silverware: RMX-specific springs and valving gave Kayaba’s new off-road version inverted forks a much smoother ride than its motocross sibling. On the trail, it was super plush but it still retained the ability to take on sand whoops and small-to-medium jumps without bottoming harshly. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Excellent silverware: RMX-specific springs and valving gave Kayaba’s new off-road version inverted forks a much smoother ride than its motocross sibling. On the trail, it was super plush but it still retained the ability to take on sand whoops and small-to-medium jumps without bottoming harshly. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension end, the RMX was at the very cutting edge of design in 1989. Initially, Halcomb and his team had wanted to stick with conventional forks for the new machine due to their superior compliance. In the end, however, the engineering and marketing teams had thought it best to go with Kayaba’s all-new inverted design. At this point, the motocross world was just starting to move away from conventional forks and the inverted alternatives were seen as trick and somewhat exotic. The theory behind the switch was that the inverted forks offered superior rigidity in high G-load situations and were less likely to get caught in ruts due to having less underhang below the axle. While the latter was certainly a bonus off-road, the increased rigidity was less valuable in a rocky creek bed than it was in a set of stadium whoops. Regardless of the new fork’s actual or perceived benefits, the decision was made that the RMX would fare better in the marketplace if its hardware were as close to RM-spec as possible.

The new Full Floater rear suspension on the RMX provided an ultra-plush ride that gobbled up trail obstacles with ease. Like the forks, it was excellent at tackling rocks and roots while still maintaining enough control for the occasional track day. It was the best rear end of the ’89 Enduro class by a significant margin. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The new Full Floater rear suspension on the RMX provided an ultra-plush ride that gobbled up trail obstacles with ease. Like the forks, it was excellent at tackling rocks and roots while still maintaining enough control for the occasional track day. It was the best rear end of the ’89 Enduro class by a significant margin. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RMX’s new 41mm inverted Kayaba forks featured a full 12.2-inches of ultra-plush travel. Both the spring rates and damping settings were lighter than on the motocross version to make the fork more responsive to the small rocks and roots the machine was likely to encounter on the trail. Like the RM, the RMX’s forks offered 20 adjustments for compression and 20 more for the rebound. Once on the trail, the forks provided a very compliant ride that gobbled up trail chatter very well. Large to medium hits were no problem and the RMX’s forks could handle anything they were likely to encounter in an Enduro. For high-speed desert work or light motocross use, they were a bit soft but even the occasional trip to the track was not out of the question as long as you kept your Guy Cooper antics to a minimum. For the RMX’s intended use these forks were excellent.

Randy Hawkins backed up his 1988 Enduro title by scoring another win for the new RMX in 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Randy Hawkins backed up his 1988 Enduro title by scoring another win for the new RMX in 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Out back, the picture was even rosier with the redesigned Full Floater offering the best ride in the ’89 250 Enduro class. The new Kayaba damper featured 12.7-inches of travel and offered 21 settings for compression and 18 adjustments for the rebound. In stock condition, the shock’s action was super smooth and compliant over rocks, roots, and other trail detritus. Like the forks, it was a bit soft for hard-core motocross use but even expert-level off-roaders praised it for its controlled action and plush feel.

While the stock RMX was not much of a performer it provided a great platform from which to make a very competitive racer. Here Mark Mangold (214), Mike Webb (314), and Tom Webb (114) put the new machine through its paces in the Idaho Enduro Qualifier. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the stock RMX was not much of a performer it provided a great platform from which to make a very competitive racer. Here Mark Mangold (214), Mike Webb (314), and Tom Webb (114) put the new machine through its paces in the Idaho Enduro Qualifier. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the handling department, the RMX was an excellent woods machine. With is slim ergonomics and supple suspension the bike felt considerably lighter than its 243-pound (Suzuki claimed a very optimistic 225lb dry weight in its literature) ready-to-ride weight would suggest. Sharing the RM chassis, the RMX was very nimble in turns and offered quick steering feel that made snaking through the trees a pleasure. With its added weight, it was not quite as nimble as the RM, but it was still the best-turning machine in the 250 Enduro class.

In 1989, the manufacturers had very different ideas about what made the perfect off-road racer. At one end was the RMX with its EPA-legal certification and full Enduro hardware. At the other end of the spectrum was the YZWR with its motocross-level performance and do-it-yourself ethos. Smack dab in the middle was KTM, which lacked the RMX’s government approval but made up for it by being the most race-ready right out of the crate. Photo Credit: Cycle World

In 1989, the manufacturers had very different ideas about what made the perfect off-road racer. At one end was the RMX with its EPA-legal certification and full Enduro hardware. At the other end of the spectrum was the YZWR with its motocross-level performance and do-it-yourself ethos. Smack dab in the middle was KTM, which lacked the RMX’s government approval but made up for it by being the most race-ready right out of the crate. Photo Credit: Cycle World

At speed, the relatively short wheelbase and aggressive motocross-style geometry made the RMX slightly busy but it was far less schizophrenic than the stock RM. The combination of the additional weight and different suspension tuning seemed to quiet down some of the motocrosser’s high-speed wandering. Neither Suzuki machine was as rock-solid at speed as the bullet-train YZWR but considering the wide-ratio transmission gave the RMX a top speed north of 80 mph any increase in stability was a welcome addition.

Randy Hawkins’ factory off-road racer in 1989 featured many off-the-shelf upgrades and a few works-only touches like the quick-access two-piece clutch cover that would not make its way into production until 1990. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Randy Hawkins’ factory off-road racer in 1989 featured many off-the-shelf upgrades and a few works-only touches like the quick-access two-piece clutch cover that would not make its way into production until 1990. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In terms of price, the RMX was a bit of a mixed bag in 1989. At $3899 it sat smack-dab between the less expensive KTM ($3839) and more costly YZWR ($3949) and ATK ($3940). Of the four it was the only one that was EPA legal and it was far better equipped than the spartan Yamaha. Of course, if you were going to race it, there was a bit of work to be done, but the same could be said of the YZWR. Compared to doing your own MX-to-Enduro conversion though, the RMX was still a great value. The large tank alone would have set you back more than the $200 difference between the RM and RMX and you would still need to pop for lights, a heavier flywheel, skid plates, and suspension mods. Even after factoring in the cost of a carb top, power valve cover, and an aftermarket silencer, the bike was a solid value and of course, it was easy to cork it back up if you decided to do a little play riding when the race day was over.

While most of the RMX’s running gear was praised for its performance in 1989 the one area that received unanimous raspberries was the stock rear disc. Once pressed it became stick, grabby, and noisy before eventually fading and giving up the ghost. Photo Credit: Cycle News

While most of the RMX’s running gear was praised for its performance in 1989 the one area that received unanimous raspberries was the stock rear disc. Once pressed it became stick, grabby, and noisy before eventually fading and giving up the ghost. Photo Credit: Cycle News

Aside from the choked-up state of the stock machine, the complaints about the new RMX were relatively few. The tank was super slim for an Enduro machine and most everyone loved the bike’s ergonomics. Tall guys wanted a higher seat, but the RMX fit most riders very well. Despite its nearly 250-pound weight, the bike felt light and the front end was easy to get off the ground over logs and trail obstacles. The stock clutch pull was super light and the plates held up well to abuse but the lack of a two-piece clutch cover was a glaring omission on a bike made for endurance races. The shift action was the smoothest in the class but the detent was fairly light and care had to be taken not to select two gears when you only wanted one. The O-ring chain and steel sprockets were heavy but far more durable than the lightweight units found on the RM. In 1989, the RM250s had issues with piston failures under hard use but the RMX’s two-ring unit proved more durable. Some people mentioned issues with suspect fork seal life and the rear brake was prone to squeaking and overheating but for the most part, the ’89 RMX250 was a very dependable machine.

The 1989 RMX250 signaled Suzuki’s commitment to bring a truly competitive Japanese racer to the off-road world. While the stock machine turned out to be a slave to too many mistresses, the basic DNA of a winner was baked in and easily accessible with a few parts swaps and a little elbow grease. Mild or wild, the RMX250 had you covered in 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1989 RMX250 signaled Suzuki’s commitment to bring a truly competitive Japanese racer to the off-road world. While the stock machine turned out to be a slave to too many mistresses, the basic DNA of a winner was baked in and easily accessible with a few parts swaps and a little elbow grease. Mild or wild, the RMX250 had you covered in 1989. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1989, Suzuki jumped back into the Enduro game with an eminently versatile but equally unfinished machine. In stock condition, the RMX was quiet, green-sticker legal, and incapable of outpowering a KDX200. With a little work, however, it was transformed into a national-caliber off-road machine capable of winning at the absolute pinnacle of the sport. After years of ignoring the off-road market, Suzuki came to win in 1989, and the result was one of the most fun and fondly-remembered machines of its era.