The news first appeared in the May 27, 1998 issue of Cycle News:

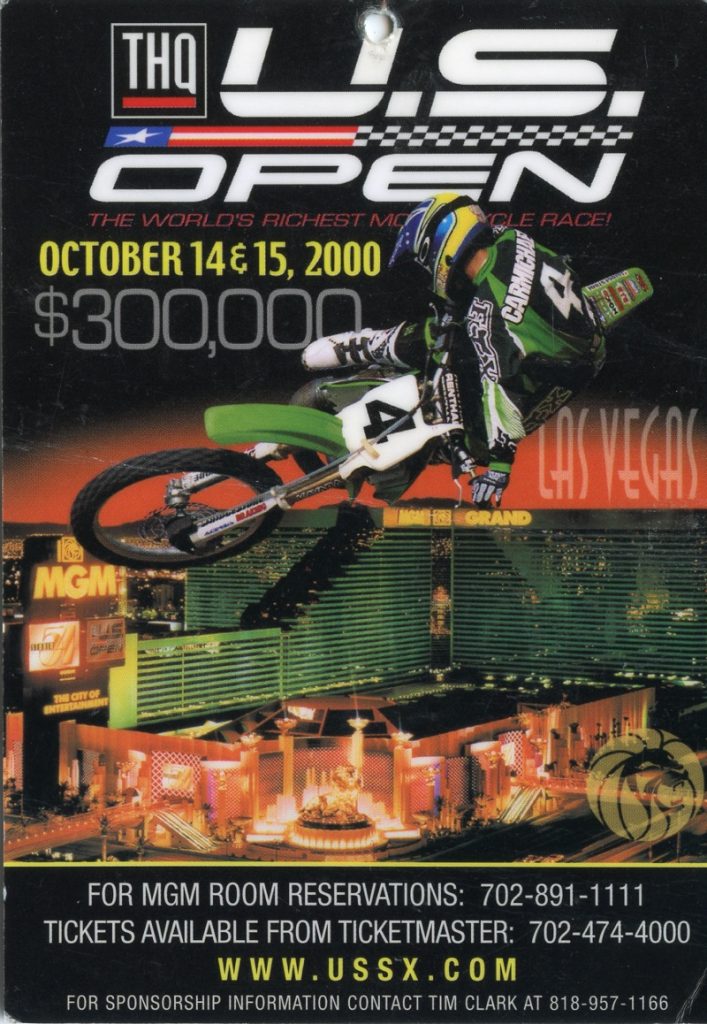

According to event promoters, the AMA-sanctioned U.S. Open of Supercross will be staged at the MGM Grand Garden in Las Vegas, Nevada, October 10-11—an invitational supercross that will feature a $250,000 purse, with the winner taking home $100,000.

Promoters Eric Peronnard and Mike DiStefano were behind this brand new race and with that kind of purse announced, the professional pits of SX/MX were buzzing….

There was just one problem: there was already a supercross series in the USA, and its promoters wanted to stop this race before it even began.

This is the oral history of the creation of the U.S. Open of Supercross.

Featuring:

Eric Peronnard: U.S. Open promoter

Damon Huffman: Factory Kawasaki rider

Jeremy McGrath: Chaparral Yamaha rider

Tim Ferry: Factory Kawasaki rider

Jeff Emig: Strategic 3 Yamaha rider

Ricky Carmichael: Factory Kawasaki/Honda/Suzuki rider

Chad Reed: Factory Yamaha rider

Jake Weimer: Factory Connection Honda rider

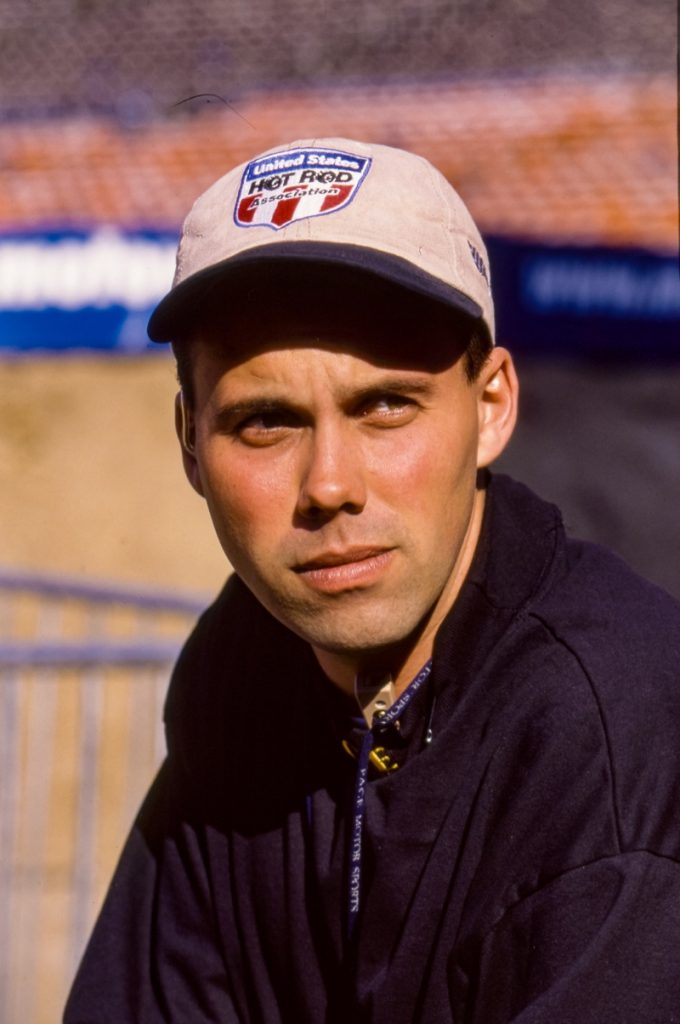

Gary Becker: President, Motorsports, Pace Motorsports

Todd Jendro: Director of Supercross, Pace Motorsports

Charlie Mancuso: Motorsports Manager, Pace Motorsports

Mark Prows: Vice-President, MGM Grand Garden Arena

Pete Fox: President, Fox Racing

Eric Johnson: Journalist, Racer X

THE BEGINNING…

Eric Peronnard (U.S. Open promoter): Basically, in the late eighties, I became very involved with all the international supercrosses. I became the go-to guy in USA to get riders to Bercy, Geneva. . . . So I became the touring manager kind of for all the riders. A lot of riders were always asking me why we were not doing races in the U.S. like we were doing in Europe. It was kind of like, I remember Jeremy [McGrath] telling me, why don’t you do a race like that here? It’s going to work. It’s going to be successful. That was kind of in the back of my mind. Then the turning point was in, I would say, 1995.

Cycle News: “It’s $100,000 to win—of course I’m excited,” said Jeremy McGrath on May 15, just prior to heading up north for the Sacramento National. “It will be a small track, but they’ll pack it up with spectators. I’m excited about it. I think it will be like the Paris Supercross – small, but very serious.”

Eric Peronnard: So I’m in the middle of my life in Vegas. I lived in Vegas from ’91 to 2001. We have a motorcycle dealership. My wife and I, we were driving from Vegas to California, and during the drive she says, “Why don’t we do a race like Bercy?” 1995-ish. That was really the wakeup call. I’m like, “Yeah, why don’t we do something like that?” I mean, I know how to do it. I’ve got pretty much the skills in my hands to make it happen. We’ve been involved in all the aspects of the races in Europe because bringing the riders is one thing, but then the next thing you know, we’re designing tracks. So all the aspects were there. There was not really a question. Quickly when we realized after that conversation that it was doable, I said, “Yeah, but where? We need a magic place.”

Cycle News: “The two promoters teamed up with Fox Racing to try and make this race something special, something not seen on this side of the Atlantic up to that point. Mimicking the flash and cash of the Bercy SX in Paris, France, this was a huge boost to the sport. . . .”

Eric Peronnard: I knew the building was magic. It was an interesting conversation, because a lot of people believed it was like Bercy, the people . . . I’m like, no. That’s Paris, and it’s a magic stadium. They call it “The Cauldron” in France. It’s like a boiling cauldron where people are just on the edge, watching what’s going on inside. It was clearly for me the key. Location, location, location. So ’95, ’96, here we are. We decide. My wife is telling me, “Hey, why don’t we do one?” I’m like, “Sure, let’s do one, but then what’s next?” What’s next was there was nowhere to do it in Las Vegas. I was convinced Las Vegas was the place.

Cycle News: “This event will be so luxurious that it will amaze people,” said Fox Racing creative director Pete Fox. “Just think—you can valet park at this race. Or, if you are staying at the MGM Casino-Hotel, you can take the elevator, walk across the carpeted casino and into the MGM Grand Garden without ever going outside.”

Cycle News: “This event will be so luxurious that it will amaze people,” said Fox Racing creative director Pete Fox. “Just think—you can valet park at this race. Or, if you are staying at the MGM Casino-Hotel, you can take the elevator, walk across the carpeted casino and into the MGM Grand Garden without ever going outside.”

Eric Peronnard: The MGM Grand hotel just had opened, but the Grand Garden Arena was not there. The next triggering point is MGM. I sought connections through my late friend, Ron Loomis. I already know they don’t want any dirt. Ron, he’s the gentlemen that was crucial in making this happen in Vegas because he was a local. He was there for 65 years of his life, so he knew everybody.

Jeff Emig (Strategic 3 Yamaha rider): Eric is a dear friend, and he has been since day one. My first experience with Eric Peronnard was the Geneva Supercross in 1989. I was just a young kid that year and was actually a pro-am. I went over to the Geneva Supercross completely unprepared, not nearly ready to ride a 250 two-stroke against the best guys in the world. Crashed. I jumped off a berm, hit a wall, and slid down the wall. I broke some bones in my foot. On the way home, Eric’s wife, Carol, who is such a sweetheart, she took care of me. Eric and Carol drove my dad and I home from LAX. So that was the beginning of our relationship.

Eric Peronnard: So Ron [Henricksen] was the backbone of the motorcycle racing in Las Vegas. He had done everything. He knew everybody in Las Vegas from the Herbst Brothers to the casino guys. He knew everybody that had any ounce of passion for dirt bikes or off-road. So any time you were having an issue, you say, “Hey, Ron, do you know somebody at the Bellagio?” “Yeah, I know so and so. I’ll give him a call.” He just got stuff done in Vegas, you know?

Damon Huffman (Factory Kawasaki rider): Eric Peronnard has always been super nice and helpful. I got to know him from going over to Bercy. I just remember the whole vibe of he wanted to take a similar type of show but bring it to America with the U.S. Open and all that.

Eric Peronnard: I told Ron, I said, “Hey, what about the MGM?” He says, “Let me find out.” Of course he knew people there. Quickly he found out that they were dirt apprehensive. That was in ’95 when we had that decision. So very quickly the project went from conception to the MGM, but they didn’t want dirt in the arena. But in ’96 Honda does the dealer convention at the MGM, and they built a mini supercross track and they put dirt—a couple lanes, but it was dirt. That was a huge turning point.

Mark Prows (Vice-president, MGM Grand Garden Arena): [MGM Grand Garden Arena] opened on New Year’s Eve of 1993. I got there just as the building was basically being delivered. Previous to that, I was doing a bunch of other things. I started at University of Wyoming and then went to a bunch of other jobs in San Francisco. Went to Thomas and Mack Center in Vegas and then out to Tacoma, Washington, and then back here. They brought me back to run the arena just as it opened.

Eric Peronnard: I heard about the Honda show, and I’m sure I called Loomis and I said, “Hey, things must be different, because they just built it.” It was Rich Winkler that did it and his crew, a good friend of mine. He said, “There were no issues. It’s very easy to build a track,” and stuff like that. So suddenly, the MGM Grand Garden Arena was no longer a virgin. It had been soiled by dirt. So that was the second step. Like, wow, we can make it! So at that stage, we were in. There was no excuse anymore. If they could open the door for a Honda convention, why not open the door to a race? So at that time, it was very interesting!

Eric Peronnard: I heard about the Honda show, and I’m sure I called Loomis and I said, “Hey, things must be different, because they just built it.” It was Rich Winkler that did it and his crew, a good friend of mine. He said, “There were no issues. It’s very easy to build a track,” and stuff like that. So suddenly, the MGM Grand Garden Arena was no longer a virgin. It had been soiled by dirt. So that was the second step. Like, wow, we can make it! So at that stage, we were in. There was no excuse anymore. If they could open the door for a Honda convention, why not open the door to a race? So at that time, it was very interesting!

Mark Prows: There was a whirlwind of things that were going on during that timeframe. I was really running the operations of the arena. We had another gentleman that was actually booking the building; I came there as a director of arena operations. So some guys got fired early on, I was transferred over to senior vice president of entertainment that was over all the other production shows and stuff like that that was going on on the property. Then there was another vice president of entertainment there. There was a guy booking boxing, and I was booking all of the other ancillary events and searching for other types.

Eric Peronnard: First, I realized that to work with MGM and me, 30 years old, I needed a heavy-hitter with me. At the time, I knew a guy named Mike DiStefano. He was a Mike Goodwin guy, who was the inventor of supercross, arguably. Mike was one of his VPs. He had a project he was doing, the Fukuoka Supercross. Fukuoka was part of a World Supercross, and I was part of the World Supercross with Paris and Geneva. So I decided to go to Fukuoka. I was part of the little crew that was in Japan for supercross, which is memorable for all of us. So there I kind of got closer to Mike. I approached him with a project. I said, “Hey, I need your help. I need somebody of your caliber to enter the MGM and be credible. I mean, I’m 30 and French!” Vegas is pretty much open-minded, but I wanted to win. I didn’t want it to fail.

Mark Prows: We were mostly looking for other sporting-type events, like the one that Eric and Mike were doing. I liked Mike. He wasn’t nearly as affable and friendly as Eric was. I didn’t really know him that well or get to know him that well. I liked him. I liked both of them, actually. Together they seemed to have a good relationship. One of them that we already had traction with at that time was the professional bull riders, so we started with them doing a bunch of things along with the PBR circuit and so on and so forth. Then we expanded, most notably into other types of MMA things, which was really kind of a “tough man” contest. Oddly enough, that was actually purchased later on by the Fertittas and became the UFC. We’ve had the distinction of creating these kinds of things in the early onset, and I was involved in all of that, if not driving the straight direction of it.

Eric Peronnard: So I’m in Japan for the SX. I run into the marketing manager of Fox at that time, Javier Estrada. I explained to him what I want to do. Javier then tells me this is what Fox wants to do also. So you have to come and see us. I knew the Fox brothers, Pete and Greg. We were not friends at the time, but they came with me to a couple Bercy races. We knew each other. So it was like, wow. Suddenly the snowball is accelerating big-time. So we are at the end of ’96 and Mike DiStefano is on board. He says, “Okay, we’ll do that together.” So we form a partnership. I come back, fly to San Jose, meet with the Foxes, we decide, and basically they were on board.

Pete Fox (President, Fox Racing): I do remember that my brother and I, for a long time, we were influenced a lot by the surf industry, surf culture, surf events. We were always really stoked on a U.S. Open of Surf, and U.S. Open of other sports. Moto, supercross—it would be so cool to have something like that, something that’s as much of a celebration of the sport as it is a race. So we had talked about that for a number of years around the same time, I think, as Terrafirma. Our love of the sport, we just wanted to try to do anything we could to just make it better. So we had talked about an event like that. We just ended up connecting with Eric. It turned out we had kind of a shared vision for an event like that. So it was very natural. We didn’t have to convince each other.

Eric Peronnard: We never talked about sponsorship until six months before the race. Basically, we just wanted to make it happen. I sat down with the Fox brothers, Pete and Greg, and they basically said, “What do you want?” I said we want the biggest purse, because we were embarrassed about how little riders were making at the time. I said, “Let’s decide what the biggest purse is going to be.” We concluded it was $300,000, and $100,000 to first place. At the time it was about what a national champion was making overseas for one race. It was maybe just Jeremy McGrath that made that kind of money at that time. Riders were getting 7-8K to win an SX then, so that would be a nice jump!

Pete Fox: So that was another thing. That was a major part, I think, of the story or the reason behind it was our frustration. I’ve never seen the financials, so I could be completely off. But our frustration with how embarrassing supercross purses are, and we thought there’s got to be a way that we can influence that to try to make that more meaningful. So that was one of the big drivers for having that big purse.

Eric Johnson (Journalist, Racer X): I was with the Fox brothers. They said, “Hey, EJ, we’re going to be heavily involved with this new race called the U.S. Open. It’s going to be at the MGM Grand. It’s going to be post-season. Eric Peronnard is involved, all these people are involved.” I’m thinking to myself, like, this is unreal. You guys got an okay to do something like this? I would never think of that. There was a supercross season and those guys were trying to build their property up. I’m thinking, U.S. Open? People started telling me very quickly, “This thing is going to be cool. This thing is going to be amazing. This thing is going to be different.” Eric Peronnard is really, really involved. The MGM is involved. The Fox family is involved. So I was just all-in. I was enthused to be in the industry.

Pete Fox: Eric was more influenced on Bercy, for sure—that’s what he was looking for. Greg and I were definitely more coming from the other sports and thinking about what they were bringing.

Eric Peronnard: We wanted it to be like Paris. We wanted it to be Paris in Vegas. There was no hiding. We didn’t lie to ourselves. We wanted it to be a Bercy in Las Vegas.

Thanks to Peronnard’s connections, he and Mike manage to get into the doors at MGM Grand Hotel and Arena to pitch the hotel/casino on holding a dirt bike race.

Thanks to Peronnard’s connections, he and Mike manage to get into the doors at MGM Grand Hotel and Arena to pitch the hotel/casino on holding a dirt bike race.

Eric Peronnard: At that point, we have a team but nothing else. Fox is on board and it’s Mike and I. That’s kind of the way I work. I like to present a project when it’s solid, not when it’s just an idea. So at that point, I remember getting a VHS of Paris SX, having to find a portable VHS player to take to the MGM. Ron Loomis got me in the door at MGM with Mark. DiStefano was involved because he was kind of knowing that environment, the big dogs of the entertainment business. But between Loomis and DiStefano, we have the meeting.

Mark Prows: So when Mike and Eric came to me and said, “We want to do an arenacross, we want to make this the same kind of thing we were doing with PBR, we want to put it indoors,” I went and researched it and I said, “Guys, the track doesn’t even fit in here, does it?” He goes, “No, it doesn’t really fit in your building.” I’m like, “Then what are we doing? I don’t understand. Why is that attractive to your industry?” They were like, “It’s all about money, baby. It’s all about money. If we put up the right purses, we get the right sponsors behind this thing, it’ll turn into something in an instant.”

Eric Peronnard: Mark likes moto. I think he was riding in the desert. He was not ignorant about motorcycles. Mark became really good friends with Hylton Beattie from Parts Unlimited now. I don’t know if they’re still good friends, but he became really good friends with Hylton over the years. Hylton was helping us. He was at FMF at the time.

Eric Peronnard: Mark likes moto. I think he was riding in the desert. He was not ignorant about motorcycles. Mark became really good friends with Hylton Beattie from Parts Unlimited now. I don’t know if they’re still good friends, but he became really good friends with Hylton over the years. Hylton was helping us. He was at FMF at the time.

Mark Prows: I’m like, “Okay, show me the details.” So they came back and they showed me how the track would work in the building, how they saw it. I got together with my operations guys and we vetted it out. Basically, the track had to zoom out through the back of our building and have a small portion of the outside part of the track. Then as they made a couple of chicanes outside the building, they’d come zooming back in the building and come flying into the arena.

Eric Peronnard: We have a meeting with Prows. I didn’t have to use my portable VHS player because they took me to the top of the MGM into the executive level—they had one up there! We sat down. We sat down with everybody. I put in the VHS. We were four people. Mark was super good. He was enthusiastic. He just oozes energy. He’s like, wow. Mark was the big boss, and below him, there was the arena manager, and those guys that were most likely shitting bricks realizing we had no idea who we were….

Mark Prows: It was like, to me, we should stay in our lane. Be the building. Be the people that support what you’re doing with the ticketing mechanisms and the massive marketing machine that we had throughout the property and everything we were doing. Don’t try to be a race promoter. Team up with the right people to find success. There’s a lot of mechanical workings—meet the riders and sponsors and everything else—that Eric and Mike delivered to this equation that I just took a flier on them. I liked the guys a lot. Honestly, our guys, when I went in to present this to our senior leadership, our president of the property, he just said … “What? What are we doing that for?” I’m like, “Guys, just be patient with me.” He goes, “Is this going to drive a casino customer?” Because that’s what it was all about at the time: if they could get the entertainment that had a lot of other ancillary spin-off, and then of course they needed sponsorship from us to help defer some of their costs such as hotel rooms and some other things. They basically said, “Your Profit and Loss is on your own. You’d better make money off of every single event, or you don’t do them.” So I went back to Mike and Eric and I said, “Guys, we’re going to need to recraft this whole deal so that we can make it work.” They wanted to do it so bad that basically I pared the sponsorship down to where we had some hotel rooms in there and some marketing, but that was pretty much it.

Eric Peronnard: I would say our presentation was flawless. We had Fox involved. Everybody knew what Fox was. Fox was super famous already. We had a veteran guy that worked with Goodwin. We had the French guy that was bringing the French flair and the idea of doing it. We were set!

Mark Prows: Eric is a very affable, friendly, charismatic guy. Not only because of the accent, but then once you get to know him and understand who he is and what he has done and accomplished inside that sport, you sit back and go, holy crap, this guy is sitting in front of me.

Eric Peronnard: We haven’t sold any sponsors yet. We’re just holding. We’re building up the project, building up the project. The launch of the progress was Vegas final in May 1998. If you put it that way, ’96 is putting all the pieces together, ’97 is to get the meeting with the MGM, get the approval, and ’98 is D-Day.

With the building secured, the race was on. Next up was getting the riders and teams to commit.

Pete Fox: We had such good friendships with all our riders and such close relationships that went way beyond your standard sponsor. That’s just the way we do things. It’s more than write a guy a check and then see them when their contract is up and you’ve got to renegotiate. So we were very comfortable and confident that we could inspire all or most of our guys to want to be part of it. Getting our guys to the U.S. Open wouldn’t be a problem.

Pete Fox: We had such good friendships with all our riders and such close relationships that went way beyond your standard sponsor. That’s just the way we do things. It’s more than write a guy a check and then see them when their contract is up and you’ve got to renegotiate. So we were very comfortable and confident that we could inspire all or most of our guys to want to be part of it. Getting our guys to the U.S. Open wouldn’t be a problem.

Eric Peronnard: At that point, I basically let Fox handle getting the riders. It was, in hindsight, a mistake, because as soon as you have a sponsored rider that is asked by his sponsor to do something, there’s always a little chip on the shoulder. We didn’t know that. We were feeling, even the Fox brothers, like we were doing something great for the sport. Nobody had any idea of making money. It was just like, we were just wanting to do it.

Eric Johnson: Eric has been around with X Games and the U.S. Open and [other things] Eric has done. At least from the exposure I had with him and working with him, I thought he was just an A+ guy. I thought he was really passionate about what he was doing. He really cared. He wanted to do the best that he could. I was just proud to be involved with it, to be honest with you.

Eric Peronnard: The MGM said, “We trust you. We believe in you, but financially we’re not taking any risks.” So everything is going through them, and there’s no money being released until we deliver the show. That was the condition. Fortunately, it worked out beautifully on all aspects because Carol and I were able to sell our dealership six months before the MGM and sell out. So we had all the cash flow to run the race. Meanwhile, the MGM was holding the entire revenue.

Mark Prows: I had a lot of faith in these guys. I believed in the financial model and I had a lot of faith that they would live up to the purses they were putting up.

Eric Peronnard: It was hundreds of thousands of dollars for two nights to rent the arena, because you’re renting it for the time to build the track also. I had John Savitsky on board for that. This project has, like ten people involved. I’m very good at keeping secrets. We’re holding that very, very tight. Ten people in the world that knew about it.

Mark Prows: My bosses, they thought I was out of my mind. As a matter of fact, I remember leaving [manager] Larry Wolf’s office and he told me, he said, “This one’s on you. Anything happens with this thing, this one’s on you.” Which I knew meant if this doesn’t meet the projections—financial projections—if this doesn’t draw the right customers, if somebody gets injured in the process, meaning more like fans and liability to where we get sued or something like that is really what he meant, that that was the end of my job. I just walked out of there and said, “If that’s what you’re going to fire me for….”

Eric Peronnard: It was a million-dollar race, right away. We added up everything, production costs. Honestly, knowing what we knew, we were not that off. I don’t remember being blown away, like, “Oh shit, we’re like a hundred grand off.” No, we were not. That was a business that I had been in for ten years. I think the only bad surprise was the dirt, because we were not allowed to use the pile of dirt that was available. Then we had to truck it from farther and it was not good dirt.

Todd Jendro (Director of Supercross, Pace Motorsports): Eric is a fantastic, unique guy. Very smart in this area. I’ve known him for more than 20 years, so a lot of respect for him.

Eric Peronnard: Just before the Las Vegas final, I went to see a couple of my … I wouldn’t say my protégés, but I am their protégé, and one of them was Mitch Payton. We went to see Mitch with my wife, and I explained to Mitch, I said, “It’s going to be a 250 race, but I want you to be aware.” I went to see Keith McCarthy at Yamaha because of me being a Yamaha dealer. I kind of told a few people. Then at that time, I needed to have AMA support. So AMA was at the end. I thought we should give them the option to support us. We asked them for their sanctioning.

Mark Prows: Although my bosses were a bit skeptical, it was super exciting to me because it was so different, and because it was Vegas and because of Eric and Mike DiStefano. They knew exactly what they were doing within the industry.

Eric Peronnard: Honda wanted on board. Ray Blank was the big guy there. He was also a big guy at the AMA. He says, “Eric, I’ll be there if the AMA is sanctioning it.” So just after the Las Vegas supercross, the day after, I walked the entire AMA gang, which none of them are there now, through the MGM Grand and showed them. They were like, “Oh my god, this is going to be great. Yes, we will sell you a supercross sanction”—at the same rate as they were selling to Pace. This is the beginning of our issues and where the catch was and where everything went sideways. I had no idea I was going to get into a region war with the world of motocross at that time.

Cycle News comes out with the press release for the U.S. Open and the plans are set—the date and purse are out there for the world to see. The buzz for the inaugural race starts, but some people who ran the SX series back then at Pace Motorsports weren’t too happy.

Eric Peronnard: I think I lost my pass privilege instantly! Press release comes out, it’s weekend of the Las Vegas SX, and suddenly I go to get my pass and there was no pass for me. I’m climbing the fence behind the Honda truck and [Jeff] Stanton says, “Why are you climbing the fence?” I tell him, “I don’t have a pass.” Even at that stage, I didn’t think there was an issue. We had done some guerilla marketing because we had hired people to put flyers on all the cars, which, I’m not sure it was legal. So we had flyers on all the cars in Vegas. Then it was the standard Cycle News, Racer X kind of push. I’m not sure we had much websites in ’98.

Todd Jendro: For us at Pace, most of what was happening at that time was the growth was centered around supercross and the acquisition of all the different promoters and consolidating them into one unified championship, and with the help of Gary Becker and Charlie Mancuso, we made that happen. There was a lot of growth centered around consolidating the championship and taking it to another level at the time and expanding.

Gary Becker (CEO, Pace Motorsports): We’re pretty upset about the race. We weren’t upset about the event. Brilliant event. Brilliant idea for an event. We’re always for anything that elevates the sport of motorcycle racing. One thing I heard from Bob Sullivan, who was SFX, and he bought all these companies, he was like, “We don’t need to go out and take other people’s business. We’re okay with our pie being 70–80 percent. I want you to build me a bigger pie. Give me more opportunities.” And that’s what Eric does. He’s just a guy that goes out and creates very cool stuff, and just a hell of a nice guy.

Todd Jendro: Gary Becker, fantastic man. What a breath of fresh air to our world. He helped us expand supercross and come up with the capital necessary to change its course. He was a great person to work with, as the head of our company.

Eric Peronnard: My wife got a call from Pace’s Roy Janson, where she was told, “Vegas is our place. We own Vegas.” My wife told him, “We have two businesses in Vegas. We live here.” He called the dealership. Just picture. It’s been a joke after, because as you know, I sold and work with him. The old Chicago guys—it’s Mancuso and his gang. Suddenly the biggest race ever being done by a motorcycle dealer in Las Vegas, that’s the only thing they know, because they don’t know me.

Todd Jendro: Riding off the popularity and the coattails of supercross, it surely didn’t meet the definition of a modern-day supercross. It was more of an arenacross at the time. So there was a little bit of angst there about the use or the term. Of course, through time and the definition, it is a bit public domain where the use of supercross can be used, but it certainly didn’t meet the definition, really, what supercross was at the time.

Charlie Mancuso (President, Pace Motorsports): In that time period, we couldn’t really be pissed off about them using the name supercross because we had already established that the name supercross by itself is a generic term. We were always aware and concerned about our competition, and welcomed it, but we took it seriously. I wouldn’t say we were pissed off. I don’t remember being pissed off.

Gary Becker: But [Eric] was calling it supercross, and supercross has a distinct definition, and his event did not meet that definition. By that time, in ’98, I’ve been doing it three years, and at the time we just invested millions of dollars into our track and the way we do business and everything we’re doing and things are great. Then Eric comes in and calls it U.S. Open of Supercross [laughs].

Eric Peronnard: Once again, my wife and I, we’re on the bubble of naiveness. We know Roy Janson is not happy and Mancuso and those guys, but whatever. We’re doing our job. We don’t feel like we’ve stepped on anybody. The AMA gave us a supercross sanction!

Gary Becker: I don’t doubt that Eric had that sanction, but the AMA had a definition of supercross, and that’s what we all lived by for all these years. We had to protect it, so I went after Eric. I sued him for a dollar.

Eric Peronnard: Let me explain to you the case. The case was very simple. AMA had made a deal with Pace for the term AMA Supercross. The definition of AMA Supercross was the stadium was at least 30,000 seats. I’ve got total respect for that deal being done, but we were not made aware of it. The AMA sold us the same supercross sanction, same price, with 15,000 seats. So technically we were an arenacross.

Pete Fox: Hell yeah I remember that fight over that word of supercross. That was mind-boggling to me. It was such an education and such an experience. How could they own that word?

Eric Peronnard: The month before the race, we had an injunction from Pace. We’re like, holy shit. They said, “You can’t use the word supercross.” A couple weeks before, we received the injunction—most likely Carol received it at the dealership—saying, “You can’t use the word supercross.”

Gary Becker: I think arenacross was starting to get pretty popular in the mid-nineties as well. I think Mike Kidd was doing some arenacross. So this was arenacross. This wasn’t a supercross. The definition of supercross is in a stadium with 25,000-plus people.

Eric Peronnard: Everything is done. We had a good, young lawyer and he basically attacked the project and went and went and went. We finalized, I think it was the day before the race. We won that case. So we were concerned, but I don’t think they could have been shutting us down completely.

Pete Fox: Whoever it was, was trying to shut it down. That was pretty wild.

Eric Peronnard: Pace tried to sue us. They sued both Mike and I. We had absolutely no…. It’s like I always said, I went to McDonald’s. They sold me a Big Mac that you’re telling me it’s not a Big Mac. Yes, you’re the competition, but you’re telling me what I got is not a Big Mac? But I paid McDonald’s for the Big Mac. So it’s like, where is the point? So without being so basic, that was the case, and they lost. So they lost and the race went on. I’m fighting Pace in court and it’s so expensive. You discover how much those things cost. We’re talking every time it’s $10,000. They were bottomless. They could spend all the money they wanted. I think they couldn’t believe what was going on. It was just very upsetting to them, but more on the pride level than anything else.

If some sort of sporting event is going on in Las Vegas, that must mean you can bet on it, right? The MGM Hotel was happy to set that up as well….

Eric Johnson: Eric called me and said, “EJ, get on a plane, go over to Vegas to the MGM Grand. This car is going to pick you up at the airport, and they’re going to take you right to the casino.” I’ll never forget it. It’s only a half hour flight to get over to Vegas from LAX. This car picks me up and they take me to the MGM and I’m walking in this big, cavernous casino. I’d never been in it. It was huge, this big green monstrosity. They were like, “Hey, we’re taking you over there.” So we roll up in front of the MGM and they take me to that sportsbook, that huge room where all the betting goes on and stuff. I’m looking around and I’m like, “Wow, this is cool.” So some guy comes out and gets me, we start walking through these hallways. I can’t even describe it. Long story short, we go down this hallway and there’s this room. They open this combination and there’s monitors. I felt like I was about to rob a bank or something. So they opened the room up and it looks like the inside of a spaceship because there’s probably hundreds of different little TV monitors with sporting events all over the world. I’m like, holy shit. Then all the betting odds, all these sports…. There’s this whole group of guys working in there. There’s four, five, six guys. A couple of them are more normal business dudes, like you’d see like a casino agent. Then there’s a couple other dudes in there, full-on geeks, pocket protectors, big, thick Coke-bottle lens glasses. I knew right away what was going on. They were the numbers guys.

Mark Prows: If you’re a promotor and you’re working with a casino and you see that the motherlode from this whole thing is really gaming, you want a piece of that gaming revenue. I explained it to them. I said, “You’re not getting any of the gaming revenue.” Then it was like, “Okay, well what about this sportsbook? Can we get a piece of the sportsbook?” Then it was like, “No, you’re not getting a piece of that either.” Then they would be like, “Okay, can we at least get the line put up on these riders?” I was like, “I’ll work on that. That seems like that would be reasonable and a good experience to be able to at least bet on these guys.” So we got that put together. It was fun.

Eric Johnson: So, long story short, I sat down with these guys. They were really nice guys. I got a huge kick out of them. Basically, we started going through the racers. They’re like, “How’s this guy going to do? How’s that guy going to do? How’s this guy going to do?” We started going through everybody. I don’t know anything about betting and odds. I’m horrible at that stuff. What happened was, within a half hour, we were totally in step. I would go through everything and talk about the math and the races and the championships and who did this and who was going to do that. These odds guys, they were totally on it. They had it figured out pretty quickly. It was basically three, four, five of us, and then as the race got closer, they flew me back there a couple more times. A couple guys got hurt or a couple guys couldn’t race, so we really had to dial it in.

Meanwhile, buzz is building for the U.S. Open of Supercross in Las Vegas, with a huge purse and all the glamour and glitz a proper Vegas show could have.

Eric Peronnard: So the MGM was keeping all our ticket revenue until the race was over. They didn’t want any dirt attached to their name, regardless. That was going to help us pay the purse. Pete [Fox] wanted to have $100 tickets. He just said, “We just have to elevate the sport. Please have $100 tickets.” I was like, maybe not too many. That was high to me. He said, “No, no, no. That’s going to work.”

Pete Fox: I remember that. I wouldn’t want anyone to take that the wrong way. I’m not the type of person … I hate gouging. I hate price gouging. I think it’s disgusting. I hate everything about that. I think you’re abusing people. On the other hand, charging people a higher price to give them something of a higher quality or something more special, I think that there’s something to that.

Eric Peronnard: Pete was right! Tickets go on sale mid-May, and within a month there’s no more tickets left. I remember it being early July. We were flying to San Jose and meeting with the Foxes. We’re like, “What do we do next?” There’s literally millions in the MGM bank. If it failed, of course there would have been no future, but the minute it was sold out, it was sold out. We didn’t have much time to be worried.

Pete Fox: At a regular supercross race, maybe the seats aren’t as good. We’re going to give them a different experience. We’re going to get them closer. This isn’t gouging people. My thing always, whether it’s with Fox or with the U.S. Open, let’s give people some kind of special experience.

Mark Prows: I think that there’s a lot of pieces and components to those ticket sales. Number one, it was what they said it was, which it was unique and different for the fan experience and that would be very attractive for ticket sales. Number two, they didn’t get greedy with the way they priced it, so it was a good value proposition for the customer. Number three, I think at the end of the day, it was sexy because it was at MGM Grand, because a lot of people wanted to be there at the time. It was a great perceived fan experience, and people could actually bet on things and so on and so forth. The fourth component, which I don’t think they’re necessarily in this order, was that we have an amazing marketing machine with MGM Resorts.

Eric Peronnard: We had our deal with the MGM. We announced the race. Within that month, we sold all the tickets and had a three-year deal with MGM for the race.

Pete Fox: I remember hearing from Eric how sales were going, and that was the buzz. I remember being very aware that it was going to be the success we had hoped.

Eric Peronnard: Fox was onboard, Maxxis was the biggest sponsor, Air Nautiques was also big. Basically, we announced the race and suddenly the phone rang and people said, “Hey, we want to be part of it.” It was like, boom boom boom. We didn’t go and choose anybody, really. The only people I remember going to ask them to work with us was the White brothers, Tom and Dan. They were so good. I wanted them to announce and be part of it. I was thinking about that four-stroke supercross that was coming. I remember going to the White brothers and saying, “Hey, you guys need to be part of that.” They were super cool.

Pete Fox: We committed early and believed in it. We had that shared vision. I remember my brother Greg and I, we worked alongside Eric the days going into the event. I remember being down at the MGM doing whatever groundwork needed to be done, and everything leading up to it. We were super involved. We wanted the thing to be a success. We got that kind of work ethic from my dad, for better or worse. If you need to pack boxes in the warehouse today, then we’re packing boxes or breaking down boxes, whatever it takes. Because you care about it so much. You’re not just going to let something slip.

Eric Peronnard: When we were building the track, I couldn’t use the dirt from the SX. We were looking at all the contractors, the typical Vegas. “No, you can’t use it, can’t use that.” Finally, Savitski [John, longtime racer and track builder] decided to go and find his own dirt. We found dirt between Boulder City and Vegas. So the cost of trucking was double, and the dirt was way too soft. I remember walking on it and it was like, “Oh God.” We knew they wouldn’t have dust, but it was bad.

Pete Fox: We were just hoping to put on a great event. I think that the purity of that mission came across. Once everybody starts looking at it as dollars and cents and business, it just changes the dynamic. Definitely at the beginning we didn’t have that. It was more about, we’re going to have tons of fun—a really fun event. We wanted everything around the event; that’s one of the reasons we wanted it in Vegas or someplace where you have racing, but then you have dinner and nightlife and fun things around the event for the fans. Not only fans—industry people, racers. It’s fun to go and be part of.

Eric Peronnard: Savitski is doing the track. [Jeff] Stanton is doing the track. It’s a free-for-all. The U.S. Open year one is like, if we build it, they will come. Stanton comes, Mark Peters comes and gives us as a hand. People are coming from everywhere in the U.S., like, “I’m so-and-so, can I help you?” All people are meaningful in the industry. I don’t want to name them. It was really a magic moment.

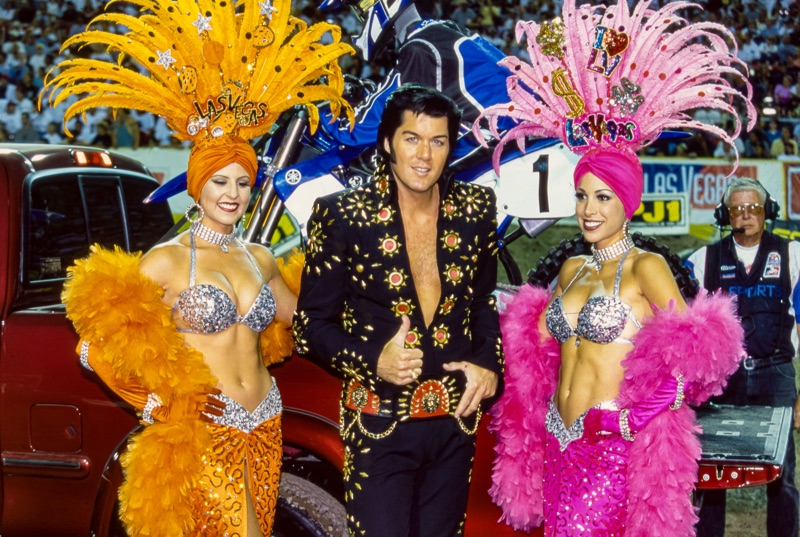

OCTOBER 10, 1998” The U.S. OPEN ARRIVES

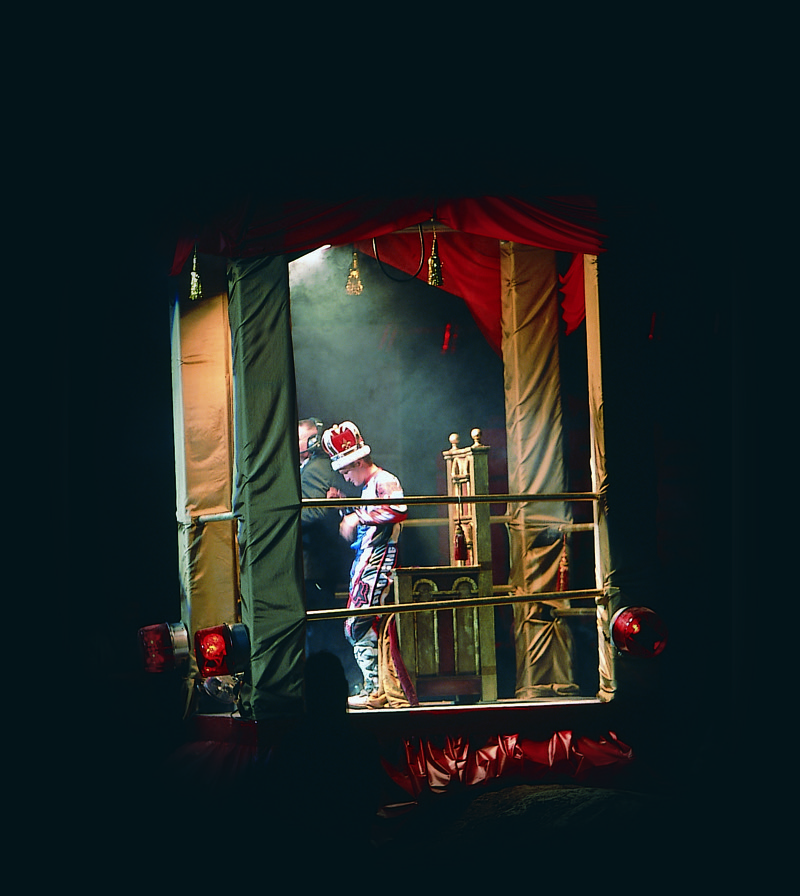

Eric Peronnard: I hired a couple guys from Hollywood for the opening ceremonies. I just wanted something big and something that didn’t look like something that was already done. I had a bunch of people from Hollywood coming, telling me they were the best and all that stuff and they could do this, they could do that. They were working in the movie industry. Working with them, we finally found that giant disco ball. That was 20 grand, then you needed 10 grand to winch it, another 10 grand to do that….

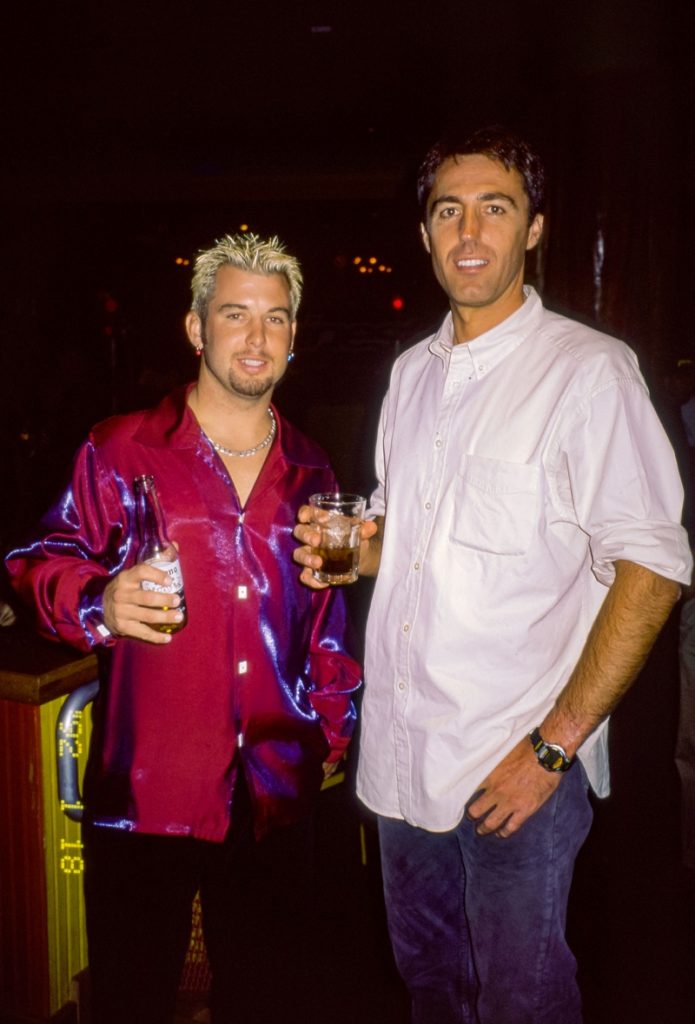

Jeff Emig: I was riding for Kawasaki and the first U.S. Open, this was during the time period I had laser surgery on my eyes and I had chipped a bone in a joint in my thumb and I had to have my thumb pinned, so I was injured the end of the championship in ’98. I remember being with Pete Fox and our whole group. I wore a suit to the first race. We were in Vegas, dude. We were doing it right. Oh, yeah.

Eric Peronnard: Pete [Fox] is super cool. Creative mind, it was his idea for the party suite on the end. He ran with that, fortunately.

Eric Johnson: You know what was cool? We would all go to work, and then it got to be like 5:00 in the afternoon and everybody was like, “Okay, we’re going to shut things down until opening ceremonies.” Then all of us would go back to our rooms and get dressed up (for motocross people). I just remember putting on nice clothes and walking through the casino and seeing everybody and the nightlife and the race. The vibe grew a couple years into it. Looking back on that, it was special.

Pete Fox: I remember being super nervous, a combination of confident, scared, nervous … which is all these emotions that I almost always feel when I’m trying to do something new. I think that’s what I’m kind of doing it all for, living for. Trying to do something like that and take some risk. Not just going through the motions. I remember feeling all of those, especially the day going into the event, being in Las Vegas, looking at the people at the MGM and them not really knowing what the heck we’re talking about. That’s kind of what gets me nervous. Usually with something moto, you’re talking to other moto people. Moto people love moto no matter how stupid the idea. They just love it so much. We all love moto. If you’re not hardcore moto they’re like, “Are you sure this is a good idea? I don’t know….” So that’s when you start questioning shit, when you’re talking to non-moto people.

Eric Johnson: I remember, like an hour and a half before the race, I ran down to the sportsbook to look around and there were motocross people everywhere in there betting. I just smiled because there was this long line and the tote boards up there, and everybody has got their motocross stuff on. I remember laughing to myself—this is pretty damn cool, man. We’re all here as fans. We all get to throw some money down if we want. The casino is in on it. The industry, the fans, everybody was pumped about it. Eric was awesome. The Fox people were awesome. The MGM was awesome.

Eric Peronnard: The opening ceremonies, the lights went dark, the lasers were out, and it’s like that’s the high of producing. You’re just like, “Oh my god, it’s happening.” Then we had the funny problems with Jeremy [McGrath] that didn’t want to stand in the ball for the time of lifting it, so we used Jimmy Lewis to stand in there.

Jeremy McGrath (Rider, Chaparral Yamaha): World Champion Jacky Vimond got lowered down from the ceiling at a race one time and crashed out in one of those things. I was like, I’m not doing that. Although I’m not scared of heights or anything like that. I enjoy all that kind of stuff, but they wanted to throw me in there at the last minute. I was like, no, I’m not doing that. I was down under the stage, and when he came down, I came out.

Eric Peronnard: Even though they lost the injunction to us before the race, I still left tickets for the Pace guys to come watch the race. I met Todd Jendro that night.

Todd Jendro: I don’t know if I would use the word spy, but I certainly was there to take in the event and see how it went and see how many people showed up. I was a well-dressed spy.

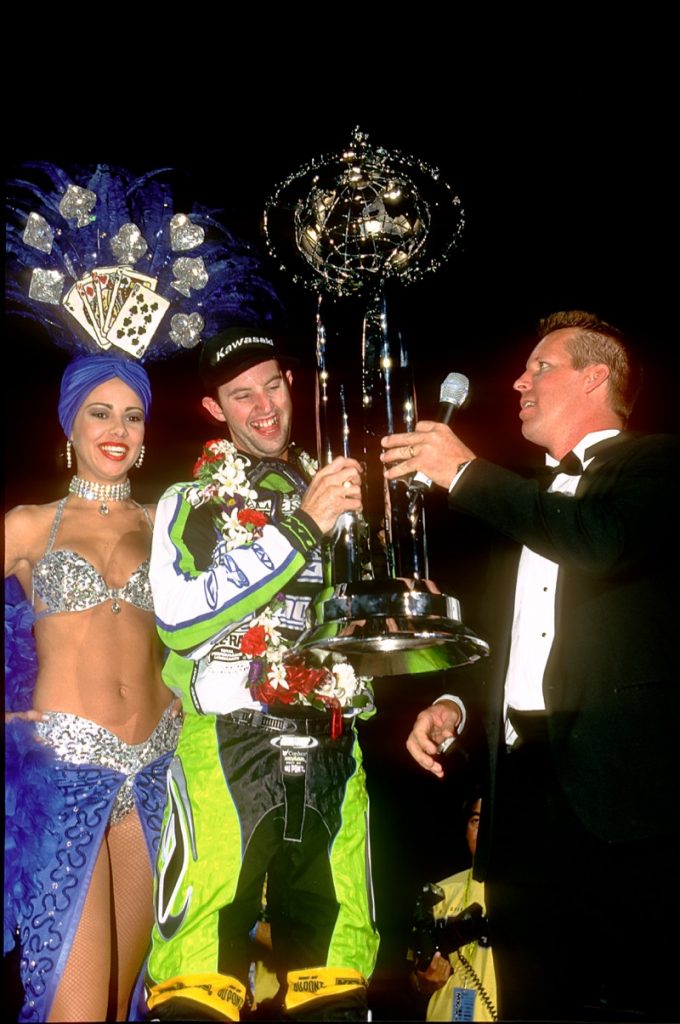

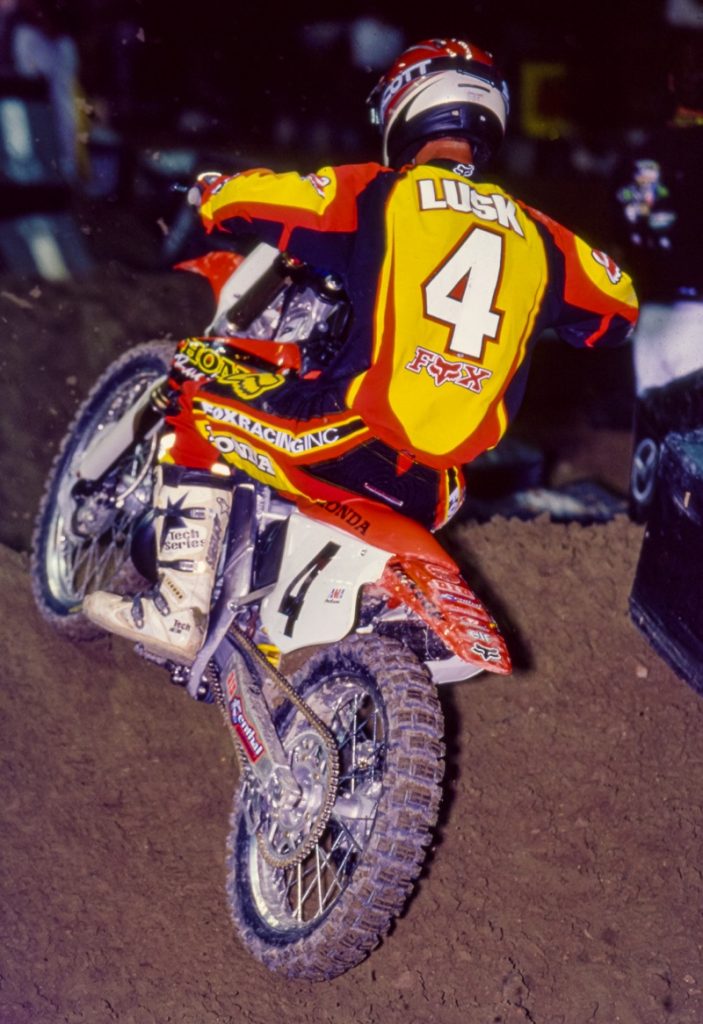

With Jeremy McGrath, Ricky Carmichael, Mike LaRocco, Arenacross champion Buddy Antunez, and more on the line, it was Kawasaki’s Damon Huffman who took the $100,000 first-place prize money with his 2-2 finishes over two nights. Kawasaki’s Ryan Hughes went 3-3 for second overall, while Jeremy McGrath went 7-1 for third. It was an unexpected result for sure, but it turned into one of Huffman’s most treasured wins.

Damon Huffman: I had a three-year deal with Kawasaki; ’98 was a little rough. I started getting some momentum. I had a podium in New Orleans, then I broke my leg in Pontiac—my femur. That was when they used to put Tuff Blox on the backside of landings. They learned from that. So I was off the whole entire summer, had multiple surgeries on my right leg. So coming into the U.S. Open, I was definitely excited. It was a weird feeling. I had low expectations.

Pete Fox: It’s funny, when I think about all my memories of the event, that race itself is kind of a blur. I don’t really remember it. I think it’s because that’s the one thing that, in my role, I had no influence or no control over the race. I had control over trying to make the party cool or the marketing cool, or make sure that the right people are there and watch some gate drops. That part is just a little bit of a blur. I do remember Bubba [James Stewart] did the second year on 80s. I remember some of that. That was some of the first exposure that a lot of people had to him.

Damon Huffman: I used to practice a lot at Mike Kiedrowski’s track. It was kind of built on a little bit of a track. His track had slope. Ironically, where his starting gate was, it was kind of a flat pad, but then it went downhill. I started riding on the bike after my surgeries, just doing little things—practicing starts, just riding around, doing some basic little jumps. I couldn’t corner that well. I didn’t want to dab my leg or anything like that, just get the feel of the bike underneath you. I did that for weeks of just riding around, maybe 50 percent but practicing a lot of starts. At Mike’s track, you had to come out of the gate and keep that weight, get your nose pointed down to get traction. So coming into the race, I felt good. I was probably 80 or 90 percent, but when I saw that starting line was elevated and then it had a pretty good little drop, I was like, “Oh, I know how to do this.” That track was pretty small and tight. It wasn’t that tough of a track. For me, I think I felt comfortable with that start and I just nailed good starts all weekend.

Jeremy McGrath: I never did win the U.S. Open. I won a night there when Huffman won it. It was one of those races that you just never knew what could happen if you got a bad start, which I did. I just didn’t get it done. I finished one position shy, I think. I had mixed emotions. I love Vegas, of course. The track was small and stuff like that. I treated that race just like an off-season European race, really. The chance to make money was awesome. For us to have that kind of a purse was another incredible moment for us in our sport. But was I disappointed that I didn’t win the race? Of course ultimately I was.

Todd Jendro: If you look back through the history of the U.S. Open, or even today the Monster Energy Cup, you will notice that there always have been different winners. From Justin Barcia to James Stewart to Ryan Villopoto. They’ve all never been expected winners.

Huffman: What did I do with the 100 grand? I gave 10 percent to [Anthony] Paggio, my mechanic. I gave another 30 percent to the government. I remember I bought myself a TAG Heuer watch. The rest just went in the bank.

Ricky Carmichael (Rider, Factory Kawasaki): Nineteen ninety-eight I was certainly in the deep end. That was at the end of my second professional year, just coming off of a great year, off the East Coast championship in the 125s and the 125 MX championship. Then a little too big for my britches. Come into the U.S. Open that year, thought I was going to do pretty well. I was just like a fish out of water. I was in the deep end for sure, way out of my comfort zone. Guys that I thought that I could beat simply were just better than me. It was a tough go at it. I was over my head.

Jeremy McGrath: I know for me, end of ’98, I was just still trying to figure out the Yamaha at that time. We didn’t really figure out the Yamaha until late that winter, and that race was October.

Todd Jendro: I just took in the event and witnessed it and came back. They did a great job with what they had. I knew that an event like this belonged within Pace’s hands. We could help elevate it and bring it to another level. We could do a lot with an event like this.

Eric Peronnard: I don’t really remember much of the racing. I was on the floor. I was working with Duke Finch, so he was making sure it was under AMA rules. I was making sure that the TV was happening and all that stuff. I just remember when we finished, I couldn’t believe it. The intensity of it was so heavy. Not only we had a race, we all know TV puts a lot of pressure suddenly. You can’t be a minute late.

Jeff Emig: It was a cool race! Because you stayed in the MGM, you never saw daylight. You just walked to the arena. You gambled, drank….

Eric Peronnard: All the teams were happy. No major complaints. It’s difficult to argue a sellout. We had a sellout. We had live TV. We had people coming from all over the world. Everybody is pretty happy to be in Las Vegas at the MGM. You’re 50 yards from your room. I’m not saying there is not people whining about something, but overall it worked well. We took everyone involved with us to Paris for the SX later on!

Todd Jendro: Initial impressions of the event is they did a fantastic job, given the space and the confines that they had, which was a glorified arena. It was larger than most hockey arenas with the expanded floor, but it was not quite a supercross. It looked and felt like most of the industry embraced the event at the time. It was a little bit of a breath of fresh air for some and a lot of work for others, who at the time just finished the supercross season and Motocross of Nations and outdoor nationals. There was a lot of “Does there really need to be another event in the calendar?” There are mixed emotions on that, even today. In 2021 there’s mixed emotions about how many events teams can fulfill and what they can do within budget and injury and attrition. But I thought that they did a fantastic job with what they had.

Pete Fox: I still have a photo of me and Ice-T. I remember him being there. I do remember quite a few celebrities. The number of people that I’ve talked to since who said, “Yeah, I was there,” just have such a strong memory of it. That’s what’s so cool. It was a fun event at the time, but it’s also something that people are carrying the memory of it. What I remember fondly was Ice-T, because of that picture. I’m sure my brother has got a better memory than me.

Eric Johnson: The biggest thing I remember is there was an upper room. You know that balcony, that viewing area? What I remember the most was when they got ready to do the opening ceremonies for that first race in ’98, I was standing there. I think I was standing there with Greg Fox, and the lights went down. The music started. Everything started going and Greg and I looked at each other. We were kind of like, “Holy shit, this is awesome. This is really cool.” It was so different.

Eric Peronnard: The event was amazing. We had tremendous profit. The riders we had worked with made a lot of money, and so did we. DiStefano and I were partners, and we paid everything at the MGM. At the end it was definitely a very, very good amount of money.

Mark Prows: What was really kind of cool, it really worked well for our slot customers. It obviously didn’t work real well with the table game customers, but our slot department, usually this stuff is aggregate. So they have a lot of other meetings in other departments, like the president of the property would, and the director of slots came in and was like, “Can we have more of that? Number one, it was an awesome event. Number two, it did actually tweak the numbers in terms of our slots.” The footfall was so high that people were looking for things to do pre-race, post-race, and in between races that it worked out pretty well. It was a huge success that way.

Eric Peronnard: The race, it was not as good as a boxing match for MGM, but in their own world, they were very happy. They were not ecstatic, because they had the Mike Tyson stuff like that. The only place that was disappointing was the gambling was definitely not on par with like a boxing. But they were ecstatic. We had right away a contract for three years.

Tim Ferry (Rider, Factory Kawasaki): I did the U.S. Open quite a few times. The first thing that comes to mind is the arena is so small. Then also the tunnel, when you go through the pillars in the back and then you go back in. I kind of like how they introduced the riders and stuff. It was very intimate, I think, much like at Bercy or something or a European race. The main thing, it was just so small inside there that I can’t even imagine guys riding it nowadays. They’d be like, “I’m not even going to do that.”

Ricky Carmichael: I just remember the vibe of that race. If you’ve been to a bunch of European supercrosses, off-season race supercrosses, and it had that feel and vibe. I really enjoyed it, despite my first couple years there. I just thought it was awesome. Killer location. Fun track. Just the atmosphere was spectacular.

Damon Huffman: It was a super exciting weekend. The only thing that was super irritating is I never got a trophy for it. Never. That trophy was the biggest and baddest trophy I would have ever had. That trophy went to Kawasaki with my bike, and they had it in their front lobby for a year, and then for the following year it went back to the actual event, and then they said they were going to make me a replica and it just never happened.

Racer X Online ran a feature back then, written by Jason Weigandt, that focused on the betting part of the race: “The funny thing is, for the first U.S. Open in 1998, Jeremy McGrath was such a dominant figure that the sports book people joked with Eric Johnson that ‘We’re not even going to touch this McGrath guy.’ He was set at 5-8 odds. But Vegas, gambling, and racing are anything but predictable. McGrath was the sure bet, but he suffered bad starts throughout the weekend and didn’t win the overall. The first U.S. Open went to Damon Huffman, who was set at 20 to 1 odds. Anyone who placed $100 on Huffman that weekend made $2,000. Eight other riders had been set with higher odds than Huffman.”

Damon Huffman: When I talk to people or they’re asking me about racing, “I won the U.S. Open. I’ve won the World Supercross title.” They’re like blown away. Like, “Whoa, the U.S. Open?” They totally associate it with golf or tennis. It was huge. It was huge at the time because I think it was the biggest prize money ever given out.

Eric Peronnard: Everybody got paid, including the 80s. Everybody was compensated. We gave $500 to each 80cc rider, and three or four thousand dollars to the last guy.

Damon Huffman: Random people came up to me, but my good friend Eric Shimp, he made a few grand on me for sure. He bet on Robbie Reynard and me, and I ended up taking it. I think Robbie won the first night.

Jeff Emig: I loved the atmosphere of it as a fan. Full disclosure, I went as a VIP that night, so it was pretty cool. I loved the idea of it. It was in our industry what we love. We love racing. The end-of-the-year race like this, to me, really needs to be a celebration, kind of an all-star event of what we just experienced in the Monster Energy Supercross Championship and Lucas Oil Pro Motocross Championship. A little bit different when you have to race, because you’re not really celebrating. It’s another job that you have to do. But really kind of a culmination of the season and celebrating all aspects of the sport.

Although the inaugural U.S. Open was a hit, Eric Peronnard and Mike DiStefano still had issues with Pace Motorsports and the use of the name supercross. The dispute finally was settled the next winter.

Eric Peronnard: January ’99, we finally have the big meeting in the golden tower in Vegas with all the expensive lawyers. Pace has two or three lawyers from New York coming with $10,000 suits. Carol and I and Mike DiStefano, we’re in those rooms and basically it’s the legal system. The AMA is completely useless…. As Gary said, AMA sold you down the river. At that time, I’m really kind of confused about what they want, short of getting us out of business. Because they’re starting to build a typical “you’re going to do a series, all the people.” What are the U.S. Open people doing? They’re going to do a series. I’m like, no. Knowing guys in Chicago that are like, we finally have real competition. They want us gone right away.

Gary Becker: Eric’s a great guy. He’s that guy that doesn’t really get mad. He just talks and he’s friendly. I have the funniest story about Eric. We’re in deposition, and I think my attorney was like…. And again, we sued him for a dollar and for him to remove the name. So none of this was financial.

Eric Peronnard: It’s not a trial, it’s just a discovery process. We have those people grilling us, trying to find like we’ve done something illegal. If we’re in bed with the AMA. I’m like, no, the AMA sold us that sanction. I think it would have been over had we dropped the name supercross, but we wouldn’t do that. It’s too important. Mike DiStefano and Fox were very insistent about it. I don’t remember what my personal opinion was, but I said, it’s a supercross. It’s what I do. I was trying to tell them. We do supercross like that all over the world. The deal that the AMA made with Pace is not defining the sport. The lawyers started to grill me. DiStefano was standard, and they were trying to discover what kind of alien I was. Carol and I, they were asking us questions and stuff like that.

Gary Becker: So my attorney says to Eric, “Tell me about you. Tell me how you got involved.” Eric says, “I’m a French guy. I’ve been in motorcycle racing most of my career over in Europe. I came to America and I want to bring my ideas.” I guess the Paris Supercross is a very high-intensity, well-produced, exciting entertainment property. He goes, “So I came here and I met my wife.” I know if anybody has met Carol, she’s a beautiful lady and a sweet lady. Then he said something like, “I didn’t work for a couple years” or something. I forgot exactly what he said. I don’t want to put words in his mouth. I remember sitting up in my chair going, “Now that’s the American dream!” Some guy moves to America, finds a beautiful young lady….

Eric Peronnard: I couldn’t hate Gary at all. I know he said it. “I cannot sue the American dream.” That triggered into a conversation where he basically says, “Do you want to work with us?” I said, “Personally, nothing would make me happier. Meanwhile, Mike DiStefano had heavy resentment for Pace. So it was right away we had that. “I would love to work with you.”

Gary Becker: I will tell you there was never any animosity. There was never any anger or any cussing at each other. It was all done in a way of two guys that just met but became instantaneous friends. We’ve been friends ever since. He’s one of the guys that, if I haven’t talked to him in five years and I talk to him, it’s like it was yesterday. He’s just that kind of guy. He does great work. He’s committed to his work. He’s been able to create some great things. I was doing some business in Las Vegas at the Orleans Arena and he brought several events there and they were just really cool events.

Eric Peronnard: DiStefano is hating those guys. He hates them. Bottom line. He has so much history with them, fighting and stuff. It was Goodwin against Pace and stuff. He knows Gary’s dad. So it’s not good. Very quickly, we disengaged. Basically, Carol and I said, it’s our project. We’re going to take care of it. You’ll be happy with the result. We engaged with Gary. Very quickly we moved to our beach house that was here. I remember we went to spend the day with Gary at the Tampa Supercross that year in ’99. So Carol and I drove to Tampa. We picked up Gary at the airport and we spent the day together, and it was a turning point. “I really would like you guys to work with us. Let’s see how we can do.” That was the beginning. It took another year. The day we spent with Gary in Tampa was the end of the war.

Charlie Mancuso: I don’t remember that whole court thing very well, but if Gary confirmed it, I sure would agree.

Gary Becker: So we went through this lawsuit, which I think lasted a day or something. It wasn’t a big deal. We got him to agree. I said, “Eric, we’re going to support you every way we can. We’re going to talk about your event. We’re going to do everything we can to make you successful. Just we’re not going to support you using the name supercross.” He still owes me a dollar, by the way.

Charlie Mancuso: Eric was just a good guy. He fit the system better than I thought, our system. Every company has got its culture and its type of people that work for a company like ours at the time. He fit within that, even though he was different and unique and respected. He had always been pretty much a lone operator. Eric and I had a super relationship. Still do, just don’t talk to him that much. I don’t talk to many people since I’ve left.

Mark Prows: It was kind of sad to see that whole thing get raveled up in just the name and nomenclature between arenacross and motocross. They deposed me a bunch of times. I just looked at these guys, guys that I knew from Pace and stuff. They were just like, “But you’ve got to know the difference.” I’m like, “No, I don’t freaking know the difference. I don’t have to know the difference.” They were actually trying to pin me down, that I had been in the industry. That was the whole deposition was that I knew, we knew what we were doing in breaching their rights. I was like, “No, I don’t.” That’s not responsibility either, but at the end of the day, they didn’t represent that anything was different or wrong either.

The next year, with Eric and Mike still running the show but the future of the race locked in with Pace, saw a big blow early when Jeremy McGrath—going through legal issues with Fox Racing when he jumped to the new No Fear gear brand—pulled out of the race. Although the biggest name in the sport wasn’t there, the 1999 U.S. Open didn’t lack for excitement.

Eric Peronnard: Fox lost Jeremy, so he wouldn’t or couldn’t come. We had Travis Pastrana, though! Jeremy was an asset to any race. Not having him was a shame. But I had been through that in my life before, not having riders that clash. Damon Bradshaw deciding not to come to Paris at the last minute back in the day for example.

Jeremy McGrath: Yeah, I didn’t race. I think it was all due to the legal stuff. Fox was suing me and whatever. It was just kind of a weird time. I was like, “I’d better not race anything right now.”

Pete Fox: I don’t remember too much of that. I remember a lot of conflict around that time.

Eric Peronnard: I told the press it was start money because I couldn’t bring up the Fox thing to the media. It was a confusing moment. Jeremy was on his way out of Fox—maybe start money would’ve worked, but there was a drama on the side that I was not involved in. I think he was a casualty of war between Fox and No Fear.

Jeremy McGrath: I don’t think it was over any start money. Once I did the race once, I kind of knew there was no start money there. Go race the race. I don’t think it would have been that. I think it probably would have more had to do with the Fox stuff than anything.

“I’ll tell you what. It feels a lot better being up here on the podium than it does being in jail.” That’s the quote the 1999 U.S. Open winner, Jeff Emig, gave to Cycle News after he went 1-2 over the two nights in an upset win at the race. Suzuki’s Greg Albertyn was the runner-up with 6-1 finishes, while Kawasaki’s Ricky Carmichael took third with a 2-5.

Jeff Emig: I had lost my ride at Kawasaki when I was arrested in Lake Havasu. I was trying to put together a program to where I could race the U.S. Open, where I could race what became a three-round world supercross championship. I was just spit-balling it. Tim Dixon and Tony Strangio and I were throwing it together daily like, “Hey, we got ourselves a tire sponsor. Hey, FMF is going to give us some money.” I had done the Fastcross before that and the first round of the world supercross championship, so those were basically preparation for the U.S. Open. So to me, that was the race for me. That was going to be the race where I come back, where I get my shit together and go, Okay, I’m down but I’m not out, and I’ll show you.

Pete Fox: Jeff’s win was really special. I was so happy for him for everything that he had gone through, the later part of his career. Kind of like for Huffman too. For somebody to have an opportunity to shine, to make a pretty good amount of money, but also you get the spotlight, the appreciation, I think that was really special.

Todd Jendro: It was kind of like a Cinderella story, the underdog. With him winning that thing, there wasn’t a whole lot of people that probably bet that he would have won any of those main events over the weekend, just given the circumstances of putting the team together late and getting things together. He was not on complete factory equipment and all that kind of stuff. So it was really great and really cool to see.

Damon Huffman: What was cool, I think the following year, if you stayed at the MGM, the little plastic key cards had a picture of me. I have one of those somewhere. It was kind of a new and exciting event here in the U.S. I liked it. I like the timing of it and calling it the U.S. Open. I wish they still called it that, because a U.S. Open is just known around the world as some huge sporting event, whatever it might be.

Ricky Carmichael: In 1999, the supercross in general was a year that I would love to forget. So we got to the U.S. Open and I felt a little more comfortable. I was able to hold my own. I think we ended up third. I like to tease my good buddy Jeff Emig about [how] he cut me off on the straightaway or on the start. I believe he did. It was the second night.

Jeff Emig: It was just all about getting the start. The track was pretty tight. There was not a lot of passing or anything like that. It really played into my hands, my strong points. Ricky gives me shit all the time that I cut him off on the start, but I’ve watched it back enough times. Even though he was on the outside of me, he cut me off. He’s the one that went wide in the first turn and left the door open. The video tells the whole story. There’s nothing left to discuss here.

Ricky Carmichael: That explains why he cut me off. He was worried about me.

Damon Huffman: That was cool for Jeff. That was unexpected kind of with his struggles at the time and all that. That was huge for him.

Jeff Emig: Albertyn was extremely fast and focused that weekend. Had he not crashed that one night, he might have been able to win it too. The bike was good. I was really focused. Crazy stuff, though. Here I have a tour bus, but we had to rent a bike to bring the bike up in. Then at the time, we had brought on a sponsor for our chain and sprockets. They made great products and all that. I don’t want to mention their name, but at the time their product was really unproven. After we had won the first night, my mechanic, Tim Dixon, really did not feel confident in the chain that we were using. So the next morning he runs across Alley Semar, who was Kevin Windham’s mechanic on American Honda. Alley maybe had stayed out a little late having some adult beverages and gambling, possibly. He was in really bad need of a Gatorade, and we happened to have a Gatorade. So Dixon says, “Hey, I’ll tell you what. I’ll give you a Gatorade if you give me one of your good chains.” Alley says, “Okay, no problem.” So he goes over to the Honda truck, gets a DID chain, and brings it over and Dixon swaps him a Gatorade, and the rest is history.

Eric Johnson: That Fro thing I remember clearly. I think that second year Tim and those guys asked me to do a big story in the program about Jeff, because Jeff had gotten into that trouble. I did this 5,000-word story called “Don’t Look Back” about Jeff. Tim and Eric put me on that. I remember going to the race that second year and Jeff won. It was a shocker. I remember a lot of us were really happy for Jeff because with the trouble he got into and all that. He came back and redeemed himself and cleaned himself up and dug himself out of the hole. I think a lot of fans and a lot of industry people were pumped with that result.

Jeff Emig: If you remember, that weekend, THQ video games had a bunch of holeshot awards and maybe laps led and some sort of things like that. I remember the total I won was $112,500. I’m sure I spent it on the race team. Paid for an 18-wheeler. After the race I was walking back through the MGM Grand back to my hotel room. I ran across Bruce Stjernstrom, who was the team manager, head of racing at Kawasaki, who just a month or so—maybe about two months before that—made the decision to let me go from Factory Kawasaki. He stopped me. We talked. He congratulated me on the win. He says, “If anybody was going to beat us this weekend, I’m happy that it was you.”

Damon Huffman: I was pretty new on the Suzuki, but I remember running a blue plate with the yellow #1, which, it looked really cool on that Suzuki. I’m not sure how I did overall. I think they started running the track more outside and back in. I just remember showing up and having the big #1 on the plate was really exciting. Jeremy McGrath never won that race, so I’ve got that on him. Which is nice.

Jeff Emig: I’ve got a side story of all side stories for you. This is a true story—let’s not let the facts get in the way of it. So I win the first night. The second night, I probably won my heat race or whatever. So I’m sitting in the tour bus. Knock on the door. My buddy Tony says, “Hey, it’s Ezra Lusk’s dad. It’s Ronny Lusk. He wants to talk to you.” I was like, “What the fuck?” He’s a competitor. He was good that weekend, even. He was in it. He says, “Ronny wants to talk to you.” Okay. All right. Send him in, I guess. Like The Godfather. Bring him in. So he comes back into the lounge so the four of us are sitting there. He’s like, “You know I don’t like you much. You’re always cutting little Ezra off,” and all this sort of stuff. He says, “But you cannot let Ricky Carmichael win this race tonight.” I’m like, “Okay, well, not my plan, but what are you getting at?” So he starts to tell me that after the finish line, everybody is going inside. You’re going to roll, and then double-triple or whatever. He says, “Little Ricky is going to go outside if you give him the chance. He’s going to go outside and he’s going to triple that first set. So if he’s behind you, you have to block him and not let him do that, because Ricky cannot win this race.” I was like, “Okay, Ronny. Cool. I appreciate the heads-up. Thanks for the advice. I will do my best.” Then he leaves the bus. Like … what? You’ve got Dungey’s dad walking into Villopoto’s rig talking to him before the main event? It was crazy.

Eric Johnson: The first year or two were really amazing, that first year in particular. My biggest flashback was just standing there with Greg and the opening ceremonies and just what another level it was.

Jeff Emig: I know that the U.S. Open wasn’t the biggest race in the world to win. It wasn’t like winning the supercross title. But for me personally, that was one of the best, most satisfying victories that I had in my entire career.

Eric Peronnard: Here I go to Anaheim in ’99 and they have lasers. They even stole the music. It’s like, guys! All night long I could hear the song because Ricky Johnson and I were talking about the selection of music. At the time we were very much into it, so we were picking up some stuff that was really underground house music, good nightclub stuff.

With two U.S. Open of Supercross races in the books, it was now under new ownership. Peronnard was still running the show, but new owners Pace Motorsports now had the final say in what was going on around the race. The uniqueness of the event evaporated as Pace worked the event into its existing agreements with the sponsors of the 17-round supercross series.

Eric Peronnard: After the second year, Gary decided, “We’re getting the race.” There were no issues. We were ready. Basically, Pace bought the event and our company and they moved on. It was funny because we didn’t know we were selling the company. We thought we were selling only the event. Carol is like, “If they buy the company, what are we going to do?” We had to create a new company on the go. It’s why we created EPCN Production, because we needed to create it right now. It was a seven-figure deal. Mike DiStefano and I, we had purely a business relationship, so it was fine. He got his big check, and he was happy. We stayed in touch a couple years and that was it.

Todd Jendro: We [at Pace] were on a growth spurt and acquisitions were on the horizon, and this just made sense at the time. That I do know. Usually when we purchased things, like NHRA or anything else, keeping the people that helped develop it is key because they were the innovators and what made it unique and different, and you’ve got to capture and understand what the essence of those events are like and what they are. Usually, those things are negotiated in on purchases and stuff to keep people around a certain amount of time. Eric is a smart man, who put that event together. They did their homework and they found that niche in there and the industry embraced it.

Charlie Mancuso: The U.S. Open was another creative way to showcase the best riders—motocross, supercross riders—in the world. It was different and unique. We tried to carry on from a production standpoint what was established the first two years, which means we certainly respected what was done. My memory was that it was just a unique, different event that enabled fans to see an event in a much different environment.

Eric Peronnard: As soon as they took over in 2000, I remember Gary telling me—because he was a guy that liked Fox as well—he was like, “I love Fox, but my guys in Chicago are putting pressure on me.” We had lunch with Pete [Fox] at the Hard Rock. It was sobering, for sure. But Pete was really cool. He said, “You know what? We did exactly what we wanted to do.” So that’s good. The idea was to show supercross was bigger and better. You pay the riders. You have a good show and all that stuff. So that was good. It was not the end of our friendship, because I’ve been working for them for 15 years after that.

Pete Fox: I remember that on one hand we were bummed not being part of it. I would say the biggest thing I was concerned about, not necessarily losing it, but just, is this the beginning of the end of this event? Because are people coming in here who don’t have the same intention that we did. But being the title sponsor of that event wasn’t making or breaking our business. We did it for the love of the sport. If somebody else is going to take it over and continue the love of the sport, then God bless them. Let’s all do this. But again, going back to the thing about looking back on business and life and thinking about it, the shit is so petty. Everything, you think it makes or breaks you, and it doesn’t.

The U.S. Open, now more streamlined with the 17-round supercross series, would go on with more and more Pace influence but still produced some great races.

Eric Peronnard: Basically in 2000, they exercised their rights. They hired me as their VP of international business and insist right away about me not worrying about the U.S. Open. “We want you to help us export monster trucks,” which I did. They created the World Supercross Sseries and wanted me there. They wanted the U.S. Open to be like the 18th supercross of the year. At that point, I have to say, personally, my dad was dying of cancer at that time, so I was fine with it. I was more concerned about my dad’s situation than I was about the race. The race was very important to me and us, though.