For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s all-new KX250 for 1992.

The all-new 1992 KX250 was Kawasaki’s second attempt at the perimeter frame concept. While far from perfect, the new machine addressed many of the complaints riders had voiced about the first-generation design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The all-new 1992 KX250 was Kawasaki’s second attempt at the perimeter frame concept. While far from perfect, the new machine addressed many of the complaints riders had voiced about the first-generation design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The early nineties were a great time for Kawasaki. After numerous struggles in the seventies and early eighties, the green team came roaring back with a succession of ever-improving machines in the mid-to-late eighties. After over a decade of being the doormat of the motocross industry, team green transformed itself into a legitimate contender with solid machines that produced class-leading power and excellent suspension.

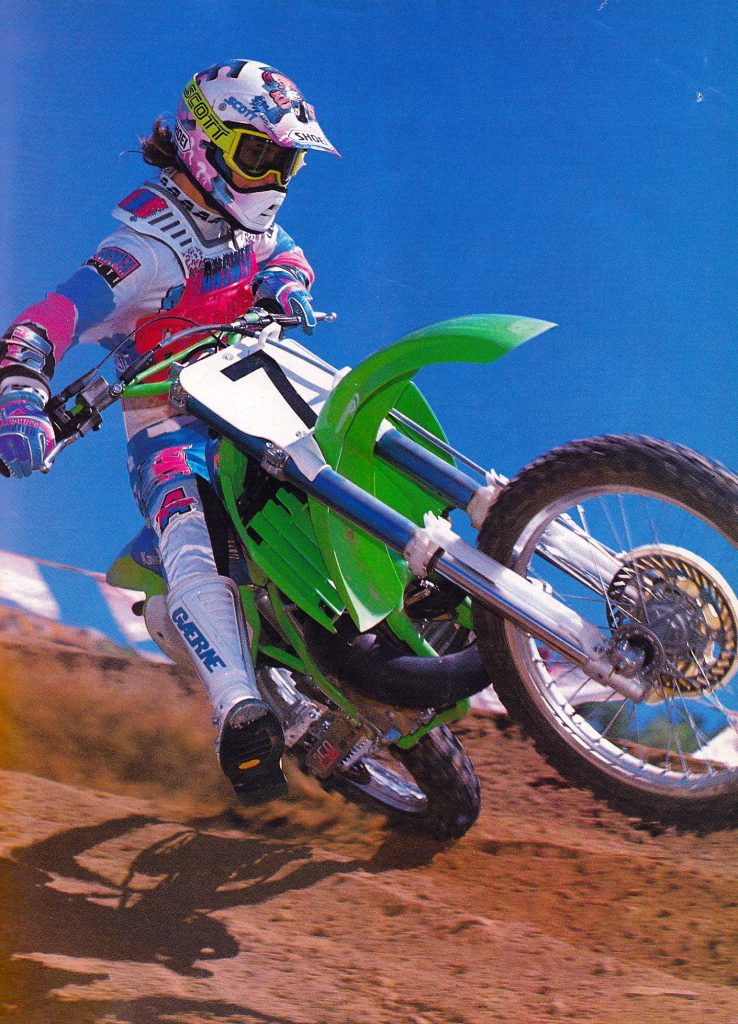

While perhaps not as striking in appearance as the original, the second generation of Kawasaki’s perimeter-framed machines were lighter, slimmer, sleeker, and more refined overall. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While perhaps not as striking in appearance as the original, the second generation of Kawasaki’s perimeter-framed machines were lighter, slimmer, sleeker, and more refined overall. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1990, Kawasaki made its boldest statement yet with the introduction of the industry’s first perimeter-framed motocross machines. The all-new KX125 and KX250 shed several years of quirky and conservative styling in favor of a new look that appeared to be a decade ahead of its predecessors. This radical redesign caught the imagination of the public and press alike and propelled the new KXs to major success on the newsstands and in Kawasaki’s showrooms.

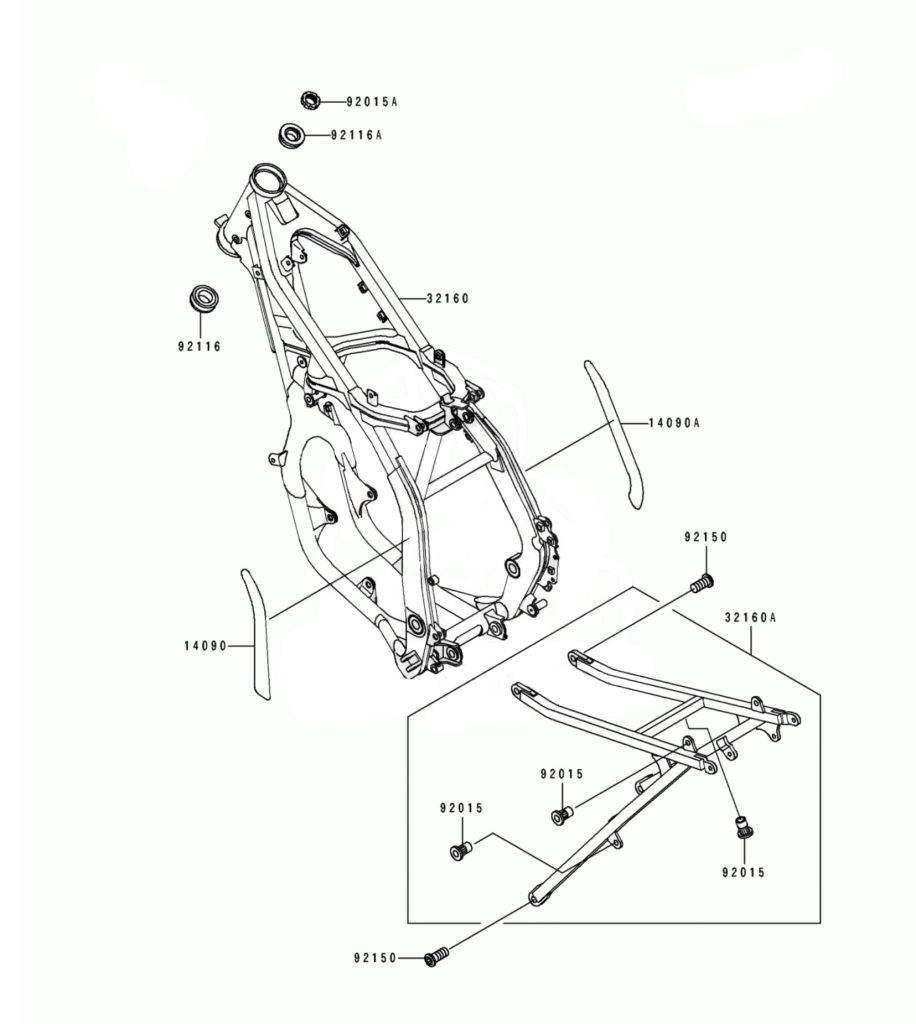

An all-new frame and redesigned bodywork for 1992 trimmed the dimensions and lowered the machine’s center of mass for improved comfort and handling. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new frame and redesigned bodywork for 1992 trimmed the dimensions and lowered the machine’s center of mass for improved comfort and handling. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the track, the 1990 KX250 proved to be a solid contender with excellent suspension and a blisteringly fast motor. The new perimeter chassis looked amazingly trick but made the bike tall and wide and some riders struggled with its Paul Bunyon feel and unique handling. There were also durability issues tied to the innovative alloy shock mounts the new frame employed, but overall, the new perimeter-framed KX250 proved to be a huge success for the brand.

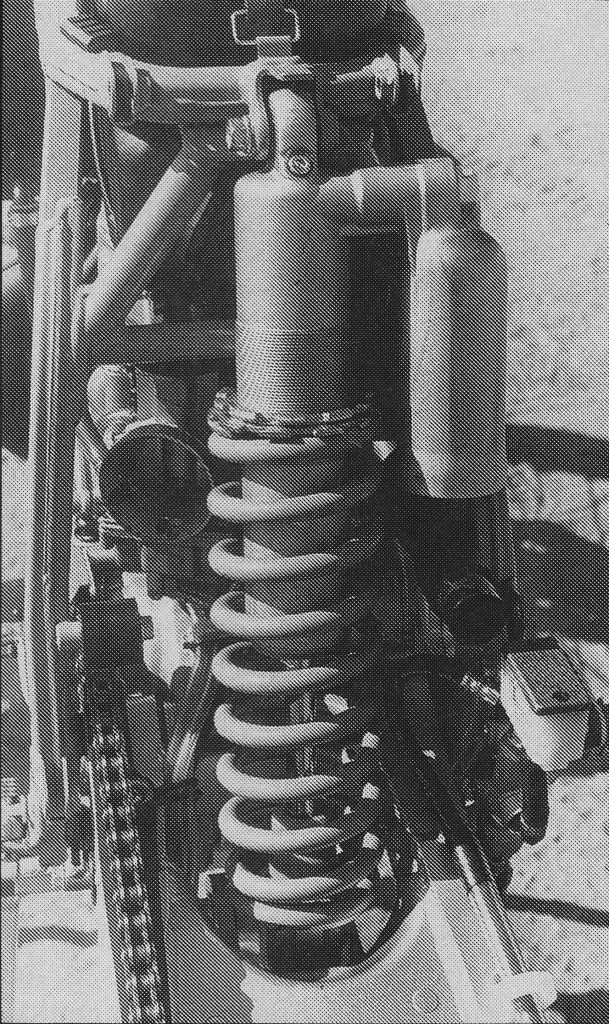

The 1990 and 1991 KXs had used removable alloy brackets to mount the shock to the frame and these units had proven prone to flexing and cracking under hard use. For 1992, Kawasaki removed this failure point and strengthened the frame by going back to a traditional welded steel construction for the shock’s mounting. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 1990 and 1991 KXs had used removable alloy brackets to mount the shock to the frame and these units had proven prone to flexing and cracking under hard use. For 1992, Kawasaki removed this failure point and strengthened the frame by going back to a traditional welded steel construction for the shock’s mounting. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

After the laurels Kawasaki received in 1990, they were content to focus on refinement for the KX250 in 1991. The large feel remained, but Kawasaki made several changes aimed at smoothing out the power and further refining the suspension. The new motor settings took away the 1990 model’s explosive hit and replaced it with a mellower delivery that pulled over a wider rpm range. This smoother power delivery was less intimidating to control, but also far less exciting to ride. Less-skilled pilots liked the more manageable powerband, but fast guys lamented the lack of hit the new motor provided. The more lethargic delivery and softer suspension settings for 1991 only exacerbated the machine’s hefty feel and most riders felt the KX needed a power boost and down-sizing program to keep up with its rivals.

The all-new chassis repositioned the tank to carry the fuel much lower on the frame for 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The all-new chassis repositioned the tank to carry the fuel much lower on the frame for 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

After only two years on the market, Kawasaki was ready to introduce another all-new machine for 1992. The new machine maintained the perimeter-framed layout of the 1991 machine but made several significant changes aimed at addressing the complaints riders had voiced in the two previous years. One issue with the first-generation frame had been unpredictability. Certain situations seemed to confuse the chassis and the bike’s front end could not always be trusted to follow its intended path despite the machine’s aggressive geometry. Kawasaki traced this issue back to the bolt-on shock mounts which allowed the backbone of the frame to flex under extreme conditions.

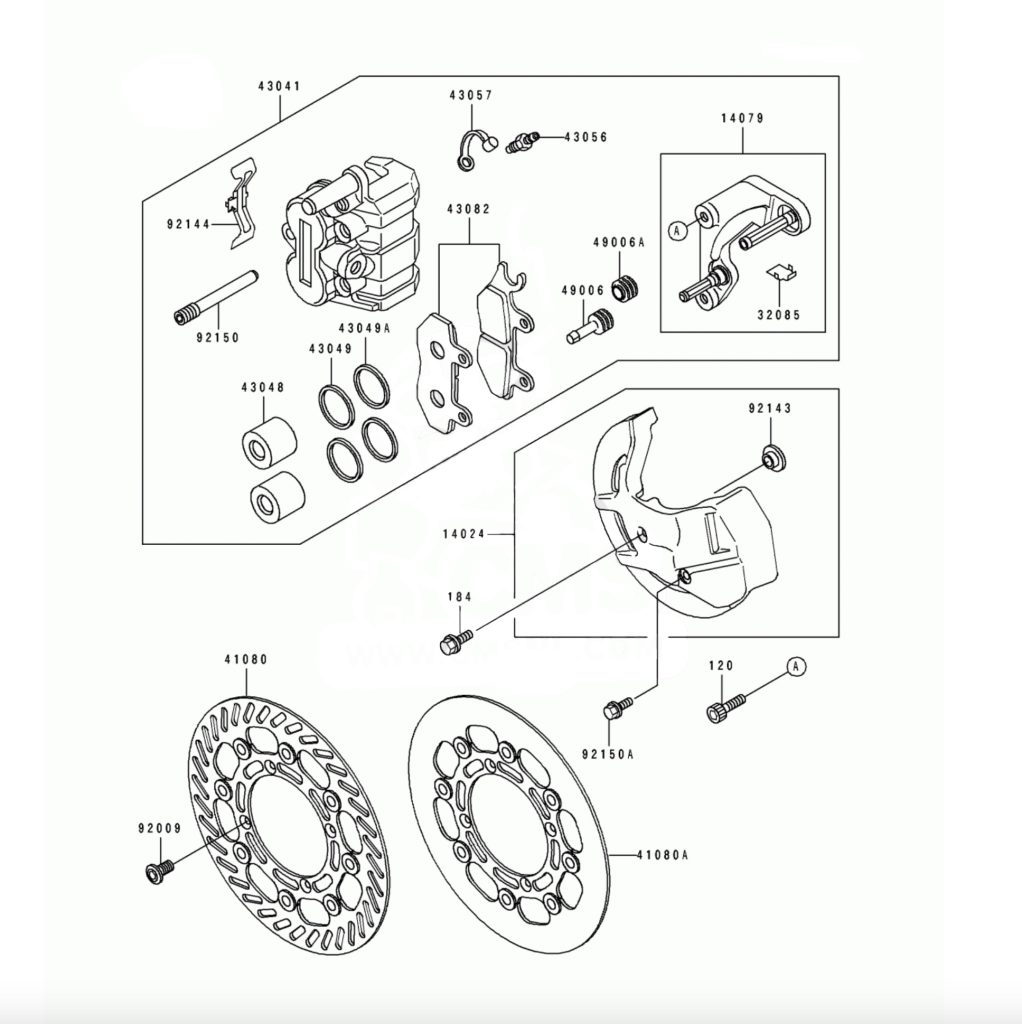

For 1992, Kawasaki borrowed a bit of tech from their factory race team and added an all-new full-floating rotor to the front of the KX. The idea behind the new rotor was to provide better pad contact by allowing the disc to self-center within the caliper through the use of eight flexible grommets. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1992, Kawasaki borrowed a bit of tech from their factory race team and added an all-new full-floating rotor to the front of the KX. The idea behind the new rotor was to provide better pad contact by allowing the disc to self-center within the caliper through the use of eight flexible grommets. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

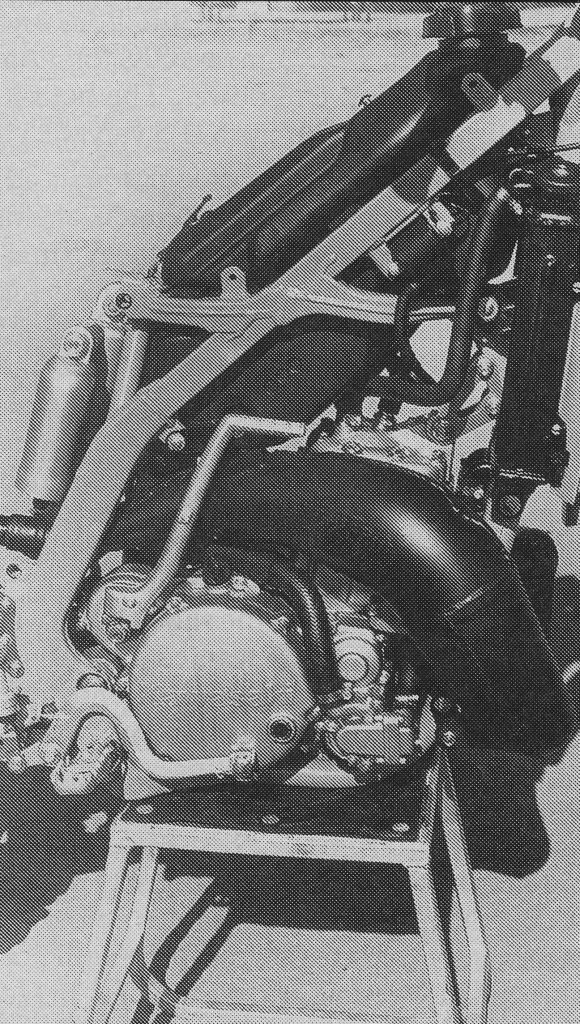

To address this and alleviate the cracking issues many riders had witnessed, the new frame employed a more traditional welded steel mount for the shock. In addition to the new shock mount, the new frame employed increased bracing behind the motor, as well as stronger gusseting of the steering head and lower frame rails. The swingarm pivot was enlarged as well and a beefed-up swingarm was bolted on to further fight chassis flex. To improve ergonomics and lessen the old bike’s top-heavy feel, both the steering head and main frame spars were mounted lower for 1992. The new spars were narrower as well to further reduce the KX’s oversized feel. In addition, overall geometry was changed with the new chassis enjoying a half-degree more rake and a half-inch more wheelbase to improve stability.

An all-new motor for 1992 redesigned the KIPS mechanism and reconfigured the bore and stroke to mimic Honda’s class-leading CR250R. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new motor for 1992 redesigned the KIPS mechanism and reconfigured the bore and stroke to mimic Honda’s class-leading CR250R. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Mated to the new frame was a redesigned Uni-Trak rear suspension system and majorly revised Kayaba front fork. For 1992, the linkage was all-new and featured a more progressive curve for smoother action. The shock remained a Kayaba unit, but the overall length of the damper was increased, and all-new valving was installed. Up front, Kayaba once again handled the damping duties with a set of inverted 43mm cartridge forks carrying over from 1991. While the forks were very similar to the year before, revised damping and stiffer springs promised improved performance.

A redesigned frame for 1992 narrowed and lowered the main spars to centralize mass and improve rider comfort. Additional bracing behind the motor, at the swingarm pivot, and in the steering head made the 1992 chassis the strongest Kawasaki had ever produced. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

A redesigned frame for 1992 narrowed and lowered the main spars to centralize mass and improve rider comfort. Additional bracing behind the motor, at the swingarm pivot, and in the steering head made the 1992 chassis the strongest Kawasaki had ever produced. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

When redesigning the KX’s chassis one of the main goals of the engineers was to improve the ergonomics and handling feel of the machine. The first-generation machine had placed the tank very high on the chassis and the overall width of the bike was noticeably more than its rivals. For 1992, Kawasaki repositioned the tank much lower on the frame and reshaped the seat to allow less obstructed rider movement. The entire rider compartment was flatter and slimmer and getting forward for turns was much easier than the year before. New radiator shrouds fully enclosed the lowered fuel tank and redesigned side plates offered a sleeker profile. Graphically, the new KX was cleaner than 1991, with a more understated look that flowed from the shrouds directly onto the seat. Like 1991, the forks remained an anodized blue that some riders liked, and others despised. At least the blue proved more robust than the red Yamaha used on its forks in 1990, which quickly turned from red to pink once the bike was exposed to a little sun.

In 1990, the all-new KX had blown people’s minds with its bold looks, but by 1992 its similar appearance seemed positively pedestrian compared to its over-the-top rivals. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1990, the all-new KX had blown people’s minds with its bold looks, but by 1992 its similar appearance seemed positively pedestrian compared to its over-the-top rivals. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

One area where Kawasaki was always an innovator was in the braking field. They were the first manufacturer to move to a front disc in 1982 and the first to add a rear disc four years later. For 1992, they once again tried to trump the field by completely redesigning their front braking system. The new ’92 design moved away from the traditional fixed rotor and floating caliper to a full-floating design Kawasaki had been employing on their works machines. The full floating arrangement was designed to allow the rotor and caliper to self-center and provide the maximum contact area at all times. In the rear, Kawasaki stayed with a traditional rotor design but did increase the size of the piston, added new pads, redesigned the heat insulator, and revised the ratio of the lever for 1992.

The all-new 249cc motor used on the ’92 KX250 produced a long and drawn-out style of power that hooked up well but lacked any sort of burst. With its smooth delivery and ultra-wide powerband, it was the easiest machine for novices to handle, but most experienced pilots longed for a bit more hit to get the bike up and over obstacles. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The all-new 249cc motor used on the ’92 KX250 produced a long and drawn-out style of power that hooked up well but lacked any sort of burst. With its smooth delivery and ultra-wide powerband, it was the easiest machine for novices to handle, but most experienced pilots longed for a bit more hit to get the bike up and over obstacles. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the motor front, Kawasaki dialed up an all-new engine for 1992. In 1991, the best motor in motocross was the one found in Honda’s CR250R. The CR’s amazing blend of smooth delivery and epic thrust was unparalleled in the off-road world. It came on at the first crack of the throttle and just never stopped pulling. For 1992, Kawasaki aimed to beef up the low-to-mid power of the KX250 while maintaining the 1991 model’s Honda-like ease of use.

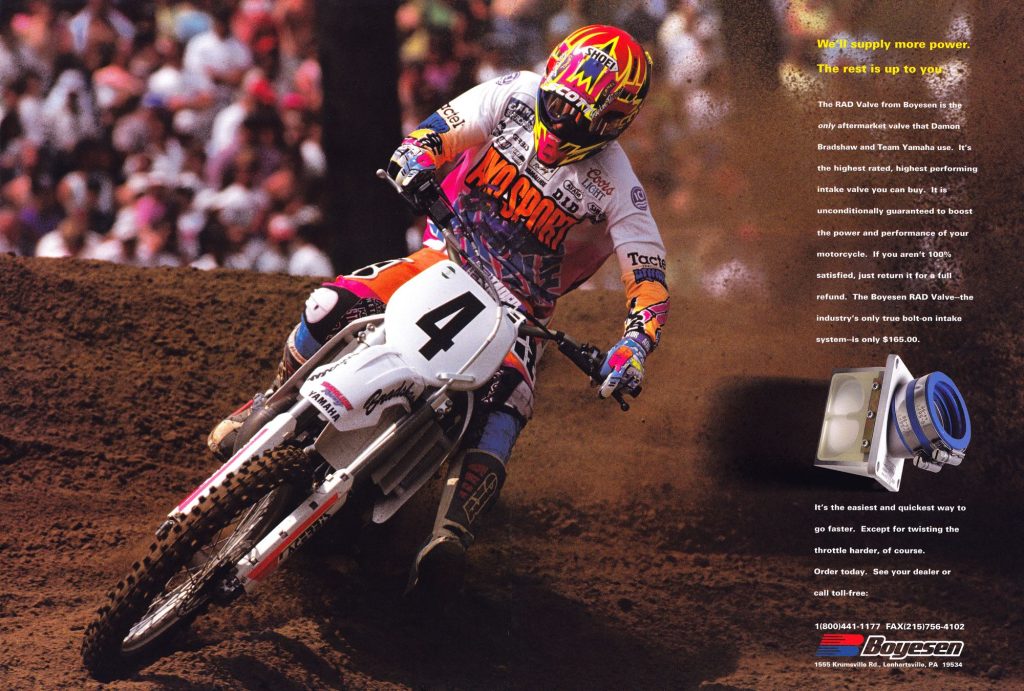

For those looking for a bit more snap out of the KX, Boyesen’s new RAD Valve was a popular and cost-effective upgrade. Photo Credit: Boyesen

For those looking for a bit more snap out of the KX, Boyesen’s new RAD Valve was a popular and cost-effective upgrade. Photo Credit: Boyesen

With its smooth and linear powerband the KX was deceptively fast. It never exploded forward like the CR or RM, but instead, put every ounce of its power it had directly to the ground. While not particularly exciting to ride, its sneaky good powerband made the bike very effective in the right hands. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With its smooth and linear powerband the KX was deceptively fast. It never exploded forward like the CR or RM, but instead, put every ounce of its power it had directly to the ground. While not particularly exciting to ride, its sneaky good powerband made the bike very effective in the right hands. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

To accomplish this Kawasaki rearranged the bore and stroke of the KX to mimic the exact dimensions found in the 1991 CR (66.4mm x 72.0mm). This new longer stroke configuration was paired with a rebalanced crank and an all-new cylinder for 1992. The cylinder, head, piston, and lower cases were all new as well to accommodate the revised internal dimensions. The new motor maintained the three-stage Kawasaki Integrated Powervalve System (KIPS) it had used since 1988 but changed the main exhaust valve to a guillotine-style for better sealing. To increase durability the new piston was coated with Nikasil on its skirts and the clutch was beefed up in size. Transmission ratios remained unchanged, but third through fifth gear were strengthened as well for increased reliability. Ignition duties were handled by new dual-generator coils that separated the spark control between low and high rpm and a revised intake system increased the volume of the airbox, airboot, and filter for 1992. Finishing off the motor package was an all-new exhaust designed to bring back some of the KX’s lost top-end.

In 1992, no other fork was even close to the performance of Kawasaki’s excellent 43mm inverted units. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1992, no other fork was even close to the performance of Kawasaki’s excellent 43mm inverted units. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the track, the new KX proved to be a highly competitive machine with a few peccadillos. If you came to the party looking for the fastest, hardest-hitting, sharpest-turning machine in the class you were going to be disappointed. Despite its all-new motor, the 1992 KX remained far more mellow than any of its competition. The new motor started pulling very early and just kept pulling over a very broad range, but it lacked any hint of burst or hit. The overall powerband mimicked the 1991 CR, but without the Honda’s verve. It was closer to an enduro-style powerband than a typical motocross mauler and most riders found it pleasant but boring to ride. That is not to say it was not competitive as the bike remained deceptively fast. Much like the 1988 CR250R, the new KX was sneaky fast and capable of running with its rivals most of the time. Deep loam and sand were an issue, but on hardpack tracks the KX’s long and smooth powerband was a bonus. Its drama-less delivery made it seem slower than it really was, and it tended to hook up and haul while its rivals spun their tires in a display of machismo bravado. For fast guys, a bit of motor work was a must but for most riders, the KX was more than capable of winning with the stock engine in place.

Much like the forks, the KX250’s shock performance was without peers in the 250 class. Ultra-plush and well-controlled, the KX had the suspension market cornered in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Much like the forks, the KX250’s shock performance was without peers in the 250 class. Ultra-plush and well-controlled, the KX had the suspension market cornered in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the motor was somewhat controversial in 1992, the KX’s suspension was anything but. The revised 43mm Kayaba forks punched out 12.2 inches of travel and offered adjustments for both compression and rebound damping. On the track, they were unparalleled in their ability to gobble up rough terrain. In 1992, nothing was as plush up front as Kawasaki’s KX250. Big hits and small were absorbed in stride and the forks suffered none of the harshness felt in the RM and CR’s front ends. Fast or heavy guys probably needed stiffer springs, but for 90% of the racing populace, the KX’s forks were dialed to perfection.

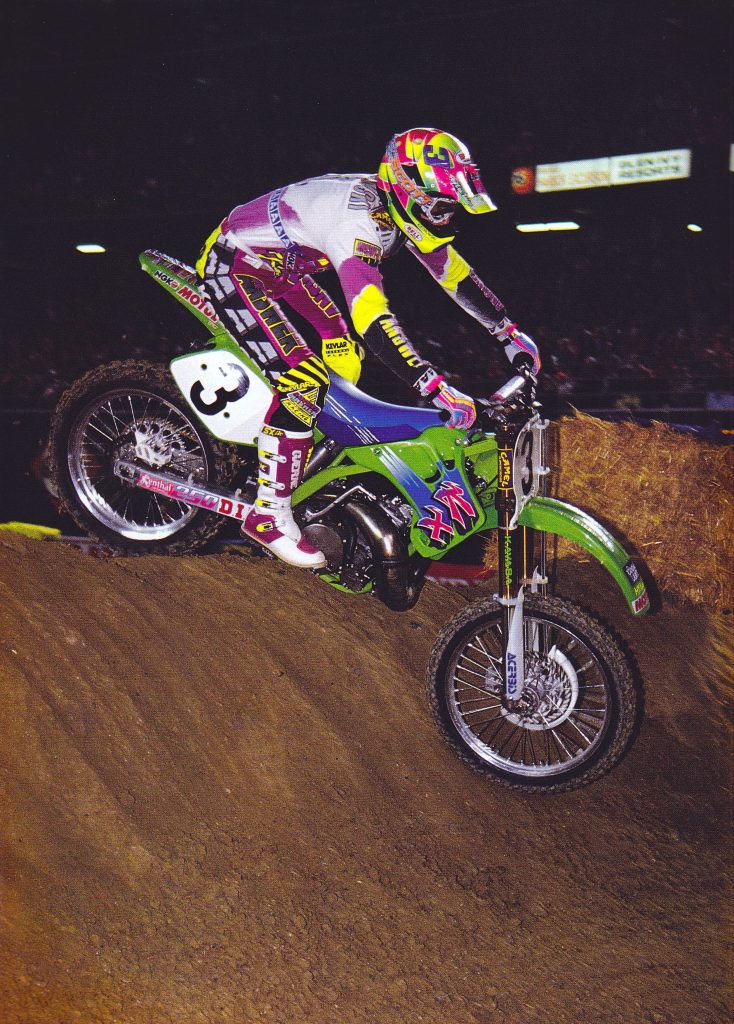

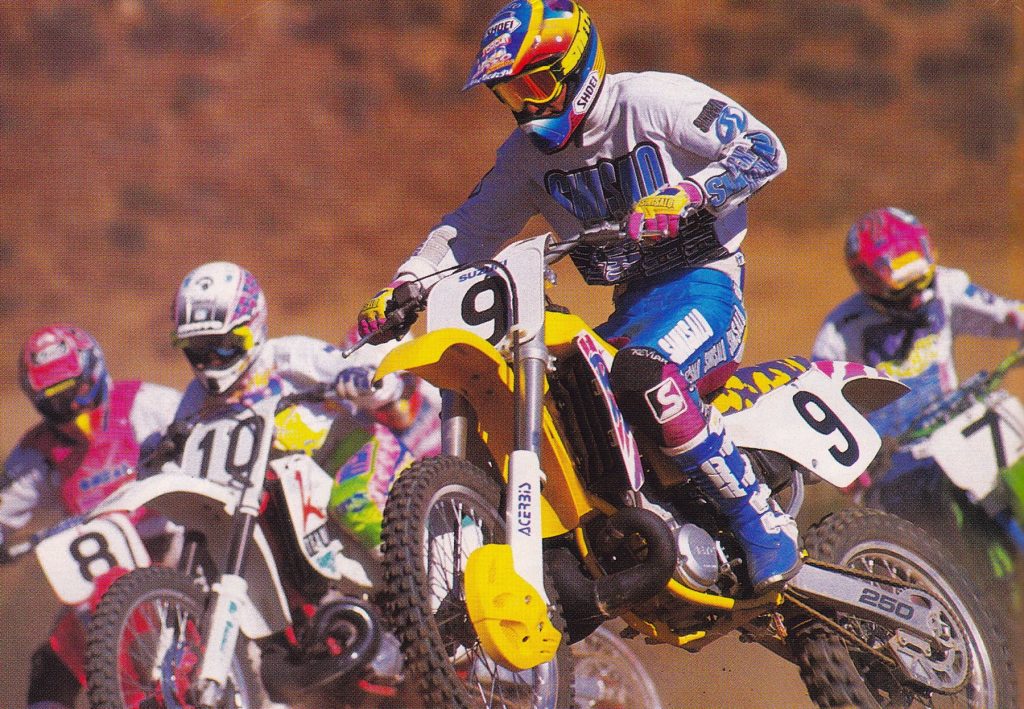

The stock KX250 was not much of a Supercross machine but careful setup and Mike Kiedrowski’s talent powered the duo to several podium finishes in 1992. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames

The stock KX250 was not much of a Supercross machine but careful setup and Mike Kiedrowski’s talent powered the duo to several podium finishes in 1992. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames

Out back, the picture was just as rosy with KX’s Uni-Trak delivering nearly flawless damping performance. Braking bumps and holes on the track disappeared under the KX’s silky smooth operation. The new Kayaba damper swallowed whoops and laughed off square edged bumps that would have had a Honda pilot searching for a second kidney belt. On a rough track, the KX’s suspension prowess was a huge advantage and that advantage only grew as the track deteriorated. As with the forks, the shock was a bit soft for pro-level guys but even they loved its performance. In 1992, there was a lot of griping about suspension performance in the 250 class but not a single one of those gripes were leveled at the green machine.

Precise cornering was not the KX250’s forte in 1992. Tight, flat, and slick turns were its kryptonite, but fast sweepers were handled with relative ease. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Precise cornering was not the KX250’s forte in 1992. Tight, flat, and slick turns were its kryptonite, but fast sweepers were handled with relative ease. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the handling front, the KX benefited greatly from its awesome suspension but its overall feel remained a bit of a mixed bag. At 212.3 pounds, the redesigned KX250 was the lightest bike in the class, but it continued to not feel that way. On the scale, it tallied in at a half-pound lighter than the feathery-feeling new CR250R, but on the track, it felt closer in weight to the portly 230-pound KTM. Some of this was probably due to its slow-feeling motor and relatively soft suspension, and some of it remained tied to its jumbo-sized chassis. Despite a Jenny Craig treatment for 1992, the KX remained a large and long-feeling bike. The steering head still felt like it was way out there, and the rider compartment was stretched out compared to the compact feel of its rivals. Riders over six feet continued to love the KX’s spacious layout, but most average-sized pilots thought it made the bike harder to throw around.

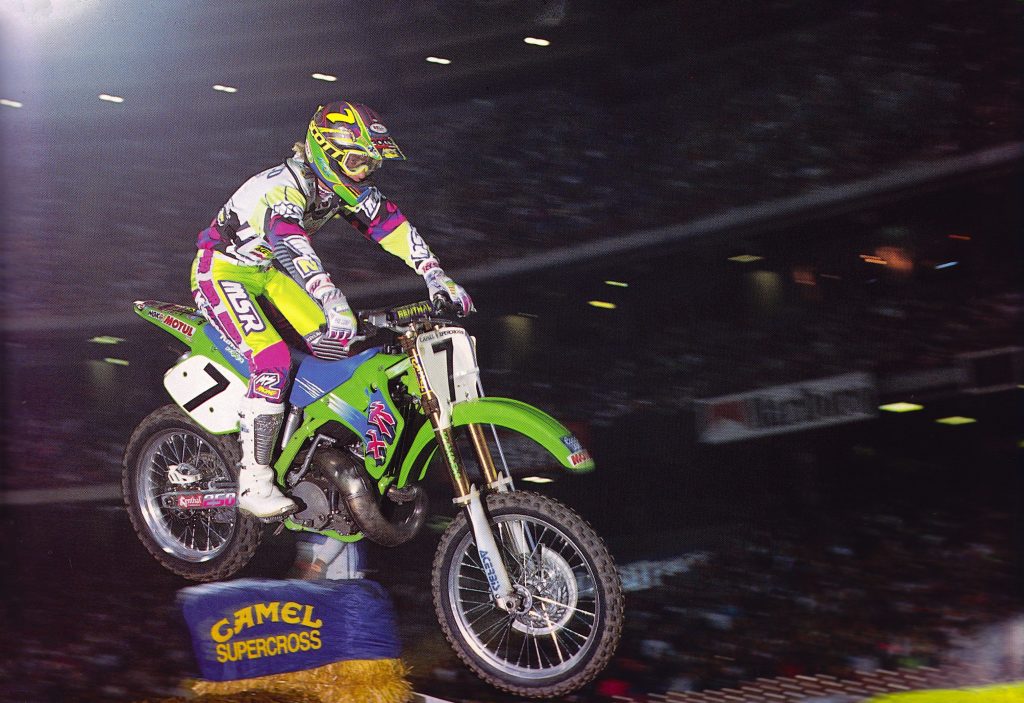

Injuries would sidetrack Mike LaRocco’s 1992 season, but he would enjoy the winner’s spoils at the season opener in Orlando on his factory Kawasaki KX250. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames

Injuries would sidetrack Mike LaRocco’s 1992 season, but he would enjoy the winner’s spoils at the season opener in Orlando on his factory Kawasaki KX250. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames

Where the KX’s large feel, slack geometry, and ultra-plush suspension paid a major dividend was at speed. Rough high-speed sections were a no-drama affair on the KX and it could be trusted to follow its intended path without any sudden hops, kicks, or shakes. The excellent suspension and stout chassis made the KX the king of whooped-out straights and the Kawasaki could be trusted in situations that would have had a Honda or Suzuki pilot puckered up like a lemon.

The 1992 250 crop of motocrossers was a very competitive lot with greatly varied strengths and weaknesses. For Supercross, the RM and CR were the best bet with the KX commanding the most respect outdoors. Of the five machines, the Yamaha YZ250 managed the do the best job of splitting the difference between indoor prowess and outdoor confidence. Photo Credit: Kawasaki.

The 1992 250 crop of motocrossers was a very competitive lot with greatly varied strengths and weaknesses. For Supercross, the RM and CR were the best bet with the KX commanding the most respect outdoors. Of the five machines, the Yamaha YZ250 managed the do the best job of splitting the difference between indoor prowess and outdoor confidence. Photo Credit: Kawasaki.

Where things went a bit astray for the new KX was in the turning department. The new chassis was stronger and less prone to flex but still far less nimble than any of its Japanese competition. Compared to the CR, the KX felt like a chopper with a raked-out front end that was in some other zip code. On flat ground, the Kawasaki exhibited an incessant front-end push, and the front wheel never really communicated what it was doing with any accuracy. Turning the front wheel felt more like a suggestion than command and the KX much preferred going straight to changing direction. On hardpack, the green machine had to be manhandled to get around turns that a CR or RM pilot could execute in their sleep. Even the only-moderately nimble YZ could turn rings around the barge-like KX. With a berm and a ton of rider input, the KX could be made to turn, but it was far happier sweeping the outside than trying to dive underneath any of its rivals.

While still a large machine, most riders appreciated the 1992 KX’s new flatter and roomier pilot’s compartment. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While still a large machine, most riders appreciated the 1992 KX’s new flatter and roomier pilot’s compartment. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the detailing side of things, the KX was innovative but slightly unrefined. The new full-floating front disc brake was works bike trick but ended up offering highly mediocre performance. It exhibited a mushy feel at the lever and a disappointing bite on the track. A switch to Motul fluid and constant bleeding made a minor improvement in the feel but the brake never offered the firm and confident action of Honda’s class-leading binders. Ironically, many riders found that the easiest fix for the marshmallow lever feel was to ditch the works-style rotor entirely and mount up the old solid-mounted rotor in its place. This greatly reduced the mushiness at the lever but even with this change, the KX remained a middling braking performer.

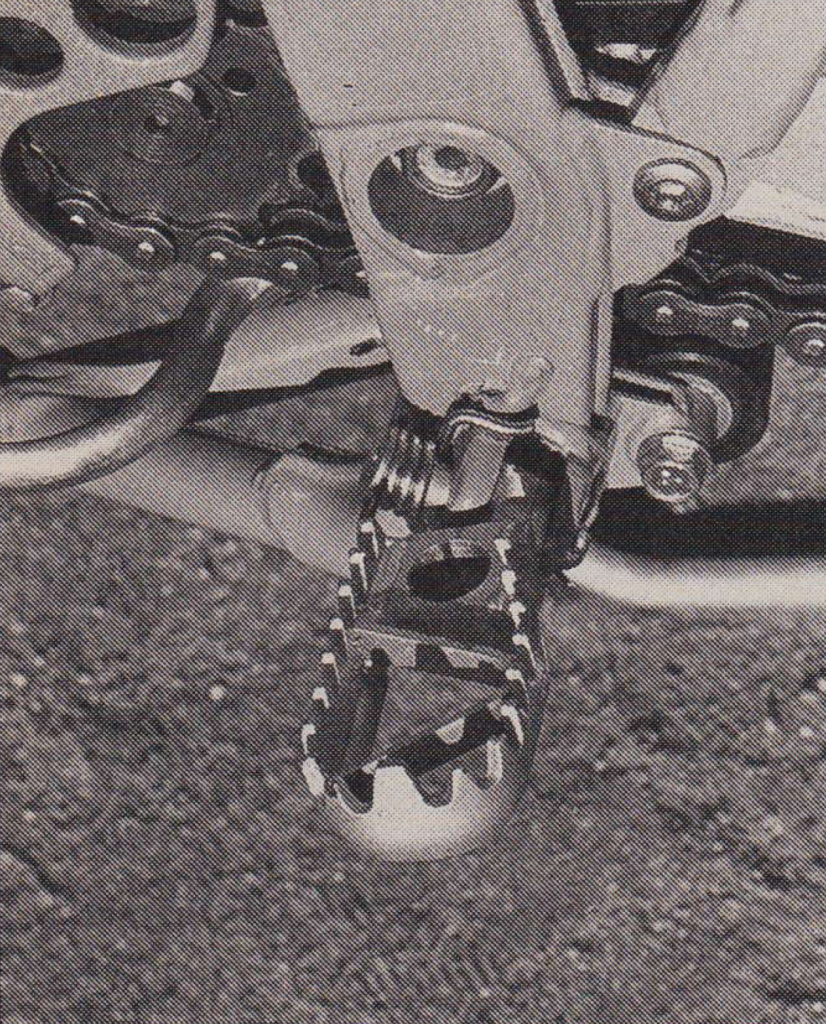

In 1992, these were the largest and most comfortable pegs in the motocross business. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1992, these were the largest and most comfortable pegs in the motocross business. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Chassis reliability was increased for 1992 with the deletion of the failure-prone upper shock mounts but the KX continued to offer the worst assortment of fasteners in the business. Seat bolts, subframe mounts, and the bike’s assorted hardware were easily stripped or broken if care was not taken with their assembly and removal. The bars, chain, and sprockets were also utter junk that lasted about as long as a snow cone on a SoCal summer day. Continuing a long line of leakers, the KX’s gas cap maintained its tradition of drooling Hi-Test if it was tightened too firmly. The footpegs also tended to droop after extended use but at least they started as, by far, the best platforms in the business. The footpeg springs were also notable for their predilection to go missing at inopportune times.

Despite a 2.1-pound weight loss and a reduction in overall size, the 1992 Kawasaki KX250 remained a large-feeling machine. In the air or on the ground this hefty feel never quite went away and the bike was harder to manhandle than its Japanese competition. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Despite a 2.1-pound weight loss and a reduction in overall size, the 1992 Kawasaki KX250 remained a large-feeling machine. In the air or on the ground this hefty feel never quite went away and the bike was harder to manhandle than its Japanese competition. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The motor was relatively slow, but at least it proved reliable. Aside from an issue some early KXs had with the Nikasil coating flaking off the piston, the motor was quite dependable. A mid-year update fixed the coating and most KXs lived on happily with only minimal maintenance. If you wanted more power, a switch to a Boyesen RAD Valve, an aftermarket exhaust, and a change in gearing greatly helped the KX’s motor feel. While it was never going to be as fast as the new Honda without major motor work, at least it was competitive and easy to ride with only minor upgrades.

Wonderfully suspended, easy to ride, and beautiful to behold, the 1992 Kawasaki KX250 was a great outdoor bike in need of a little hit and a bit of turning finesse. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Wonderfully suspended, easy to ride, and beautiful to behold, the 1992 Kawasaki KX250 was a great outdoor bike in need of a little hit and a bit of turning finesse. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the 1992 Kawasaki KX250 proved once again to be one of the most unique offerings in motocross. Its jumbo ergonomics and superb suspension seemed tailor-made for larger riders that were likely to find its lazy motor disappointing. In an era where Supercross was becoming the de facto standard for motocross handling, the KX was a bit of a throwback to a time when high speeds and rough terrain were the targets. Big, soft, and comfy, the KX made mincemeat of high-speed tracks with freight train-like stability, a predictable motor, and magic carpet suspension. For tight tracks and McGrath-style heroics, there were certainly better choices available, but if suspension excellence, comfort, and ease of use were on your wish list, then the 1992 KX250 had just what the doctor ordered.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com