For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s KX125 for 1996.

In the third year of its development cycle, Kawasaki’s KX125 adopted a bold new look for 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the third year of its development cycle, Kawasaki’s KX125 adopted a bold new look for 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

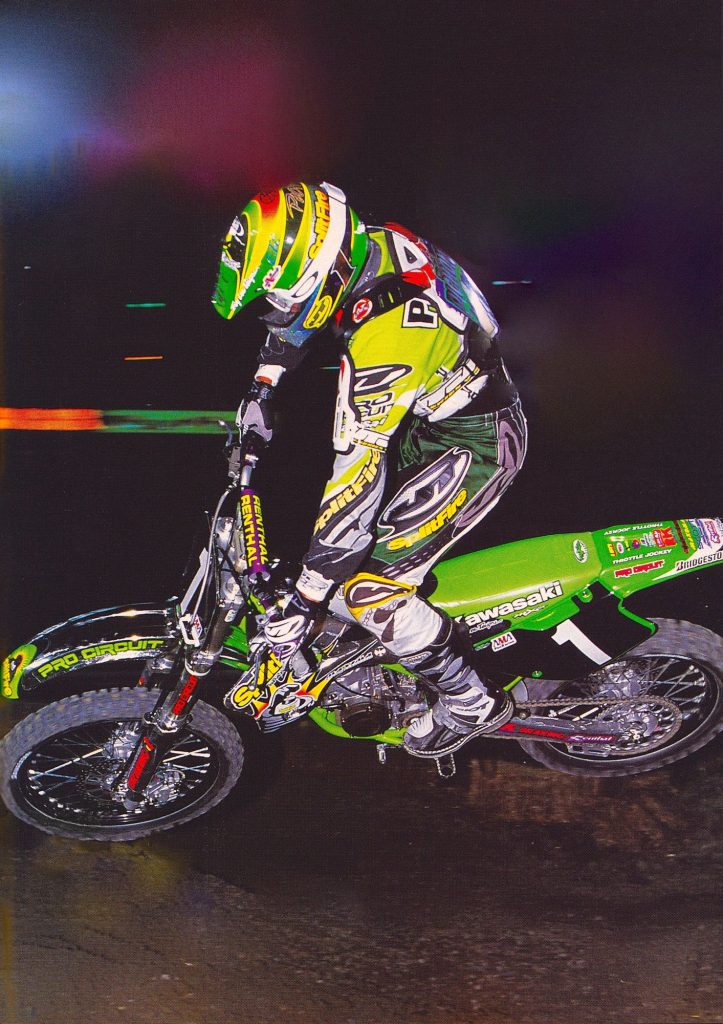

In 1995, Kawasaki was coming off a very successful year of 125 racing. Michael Pichon took his Pro Circuit-tuned KX125 to the 125 East Coast Supercross crown and his teammate Ryan Hughes came within five points of capturing his first 125 National Motocross title in a nail-biter of a season that came down to a winner-take-all battle in the final moto of the season. In this race, Hughes was unable to best his season-long rival Steve Lamson, conceding the Honda rider his first AMA 125 Motocross title. The punctuation to this epic battle was one of the most iconic moments in motocross history with Hughes forced to push his KX125 to the finish after a chain let go only feet from the finish. Although this failure was a bitter end to a successful season, there could be no doubt that Pro Circuit’s KX125s had the firepower to run at the front.

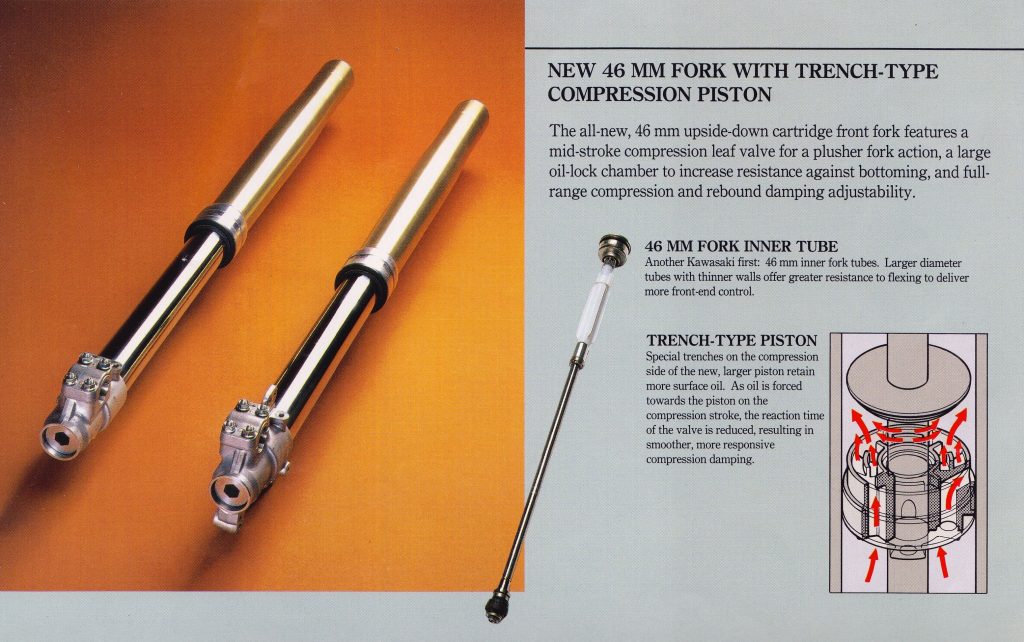

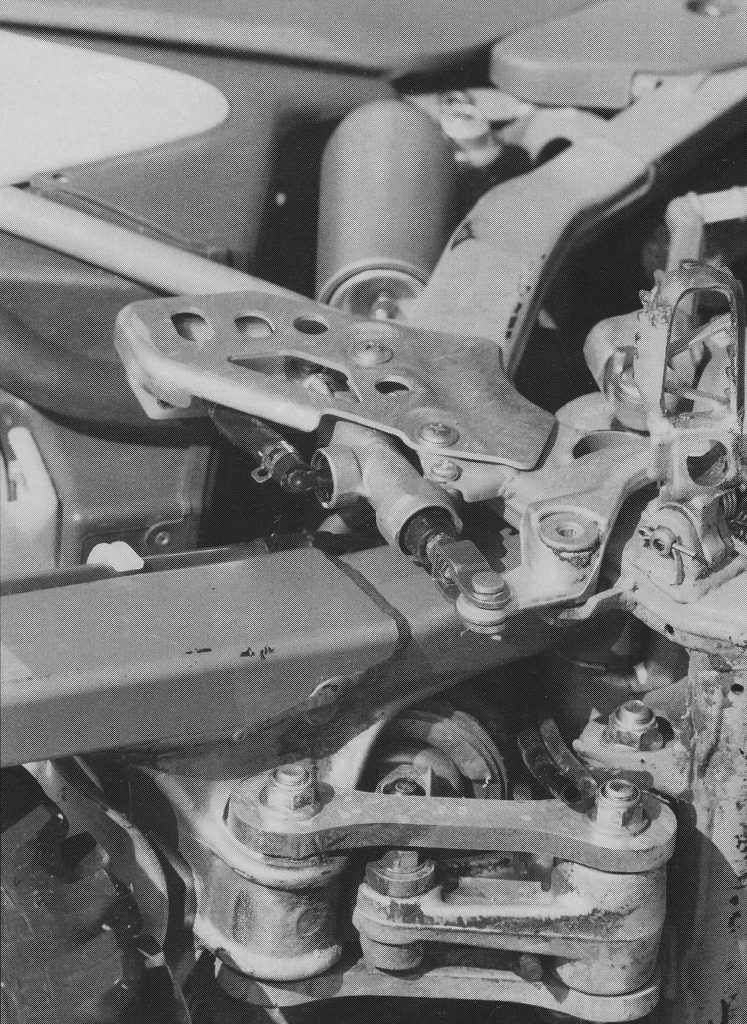

All-new forks for 1996 grew in size by 3mm and added a new larger piston and works-style damping system to provide a smoother response and more consistent damping performance. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new forks for 1996 grew in size by 3mm and added a new larger piston and works-style damping system to provide a smoother response and more consistent damping performance. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the race team’s machines had little trouble running with the class heavyweights, the stock KX125 was considerably less of a fire-breather in 1995. A punchy midrange made the KX fun, but its narrow powerband, reluctant shifting, and utter lack of top-end pull left it sucking on the vapor trail of rev rockets like the Honda CR125R. Great ergonomics, excellent handling, and solid forks made for a competitive racer, but its peaky motor and notchy transmission placed it behind more well-rounded packages like Suzuki’s RM125 in the final 1995 125 motocross standings.

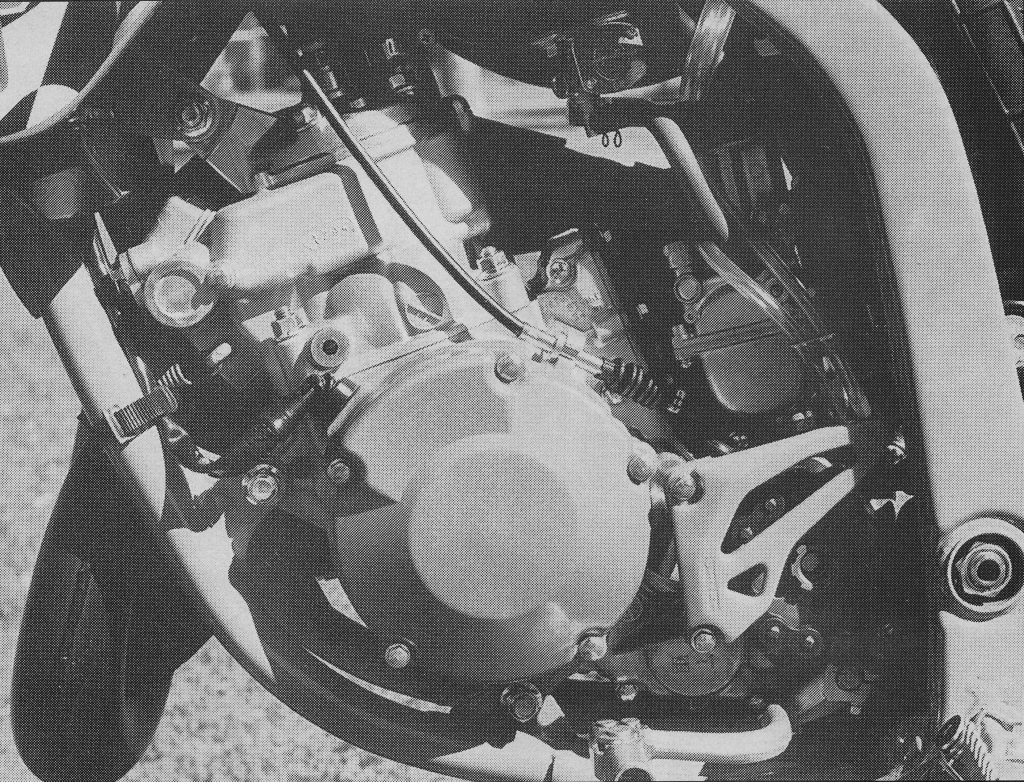

An all-new 35mm Keihin PWK carburetor for 1996 added small veins to the venturi to increase intake velocity and reduce turbulence. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new 35mm Keihin PWK carburetor for 1996 added small veins to the venturi to increase intake velocity and reduce turbulence. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1996, Kawasaki looked to catapult their 125 to the front by dialing up several significant changes to their underperforming motor. First up was an all-new top end that maintained the same 54 x 54mm bore and stroke for 124cc of displacement as in 1995 but added increased compression, revised sub-exhaust, transfer ports, and a remapped ignition. The KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) variable exhaust mechanism was revamped with a new nonlocking ball mechanism for more precise action. The exhaust pipe was new, with a thicker head pipe and revised mounting bracket for increased durability. Feeding fuel to the motor was an all-new 35mm Keihin PWK35 carburetor and revamped 4-petal carbon fiber (epoxy resin in 1995) reed valve. The carburetor’s major innovation for 1995 was a new set of veins built into the venturi that were designed to reduce turbulence around the needle jet and increase the velocity of air moving through the carburetor. Kawasaki claimed the combination of the new “bat wing” carb and ultra-responsive reeds would result in increased throttle response and better low-end performance.

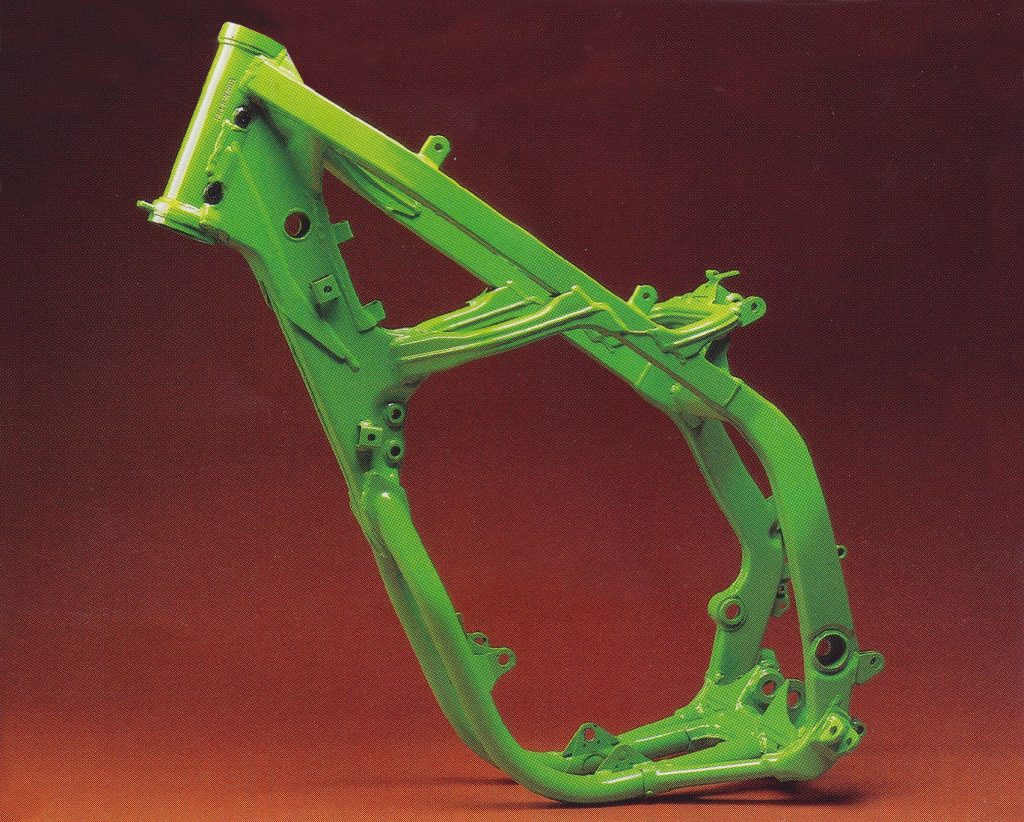

In use since 1990, Kawasaki’s perimeter frame was unique among Japanese manufacturers. Small changes for 1996 added additional bracing for improved handling and durability. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In use since 1990, Kawasaki’s perimeter frame was unique among Japanese manufacturers. Small changes for 1996 added additional bracing for improved handling and durability. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the bottom end, Kawasaki looked to address their transmission issues by beefing up the shift forks and shift mechanism and altering the shape of the shifter. For improved durability, the clutch was also upgraded with a new conical spring and washer system. Final drive gearing was moved from 12/49 to 13/50 to work best with the power characteristics of the new motor. The chain guide was also redesigned in 1996 to allow a wider variety of rear sprocket sizes to be used.

An all-new cylinder, revised ignition, revamped reeds, and massaged power-valve system looked to broaden the KX’s punchy but narrow powerband for 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

An all-new cylinder, revised ignition, revamped reeds, and massaged power-valve system looked to broaden the KX’s punchy but narrow powerband for 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the chassis front, the most significant updates for 1996 were the KX’s new forks. These new forks increased the diameter of the outer tubes by 3mm and added a redesigned cartridge system which featured a mid-stroke compression relief valve and a larger oil-lock chamber. These features were designed to deliver smoother damping performance and improve bottoming feel under full compression. The cartridge piston was also increased in size and moved to a “trench-type” design which retained more surface oil to provide faster and smother operation throughout the travel. While the forks were larger in diameter, their weight was kept in check by reducing the thickness of the outer tubes. This also allowed Kawasaki’s engineers to dial back some of the stiffness the new larger diameter forks provided to optimize steering and chassis feel. As in 1995, the forks remained fully adjustable with 18 settings available for compression and rebound damping performance.

A 16-year-old Ricky Carmichael was one of Kawasaki’s most-heralded up-and-coming stars on the KX125 in 1996. Photo Credit: Thom Veety

A 16-year-old Ricky Carmichael was one of Kawasaki’s most-heralded up-and-coming stars on the KX125 in 1996. Photo Credit: Thom Veety

In the rear, the shock remained largely unchanged, but the engineers did revamp the Uni-Trak system by changing the curve of the linkage to be more linear through its travel. This was done to improve tracking in the rough and allow the shock to better follow the terrain for improved hook-up. The swingarm pivot was also upgraded with additional bracing and a new “thrust bearing” design that Kawasaki claimed reduced flex for more precise handling.

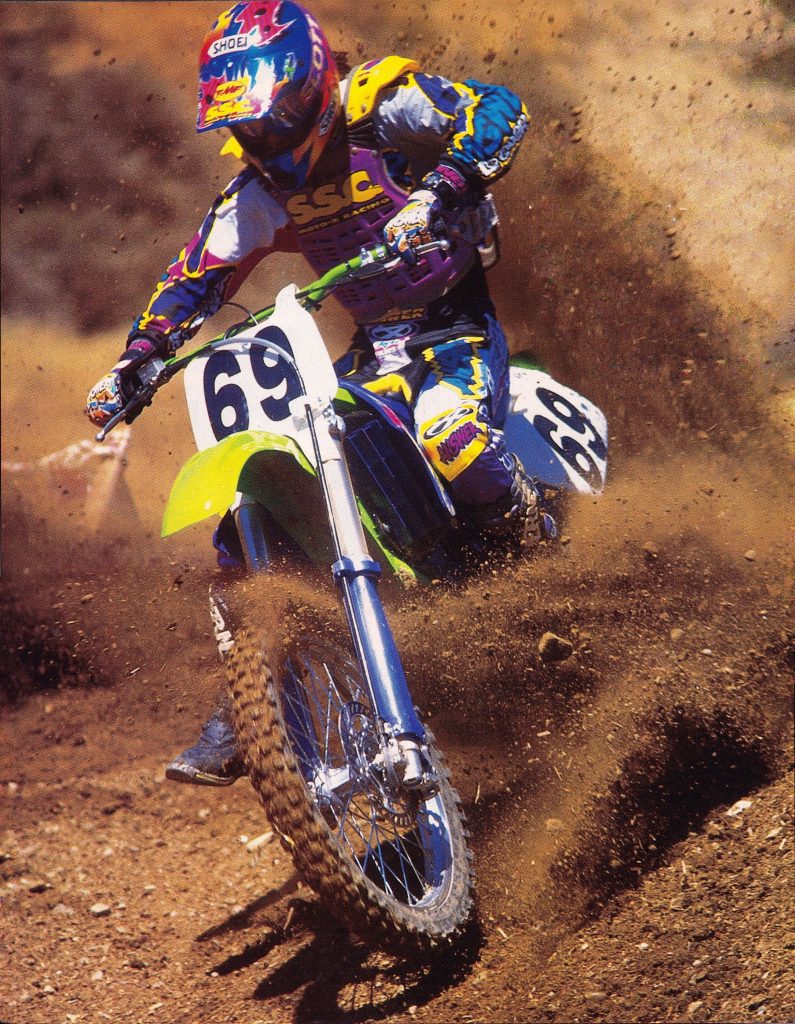

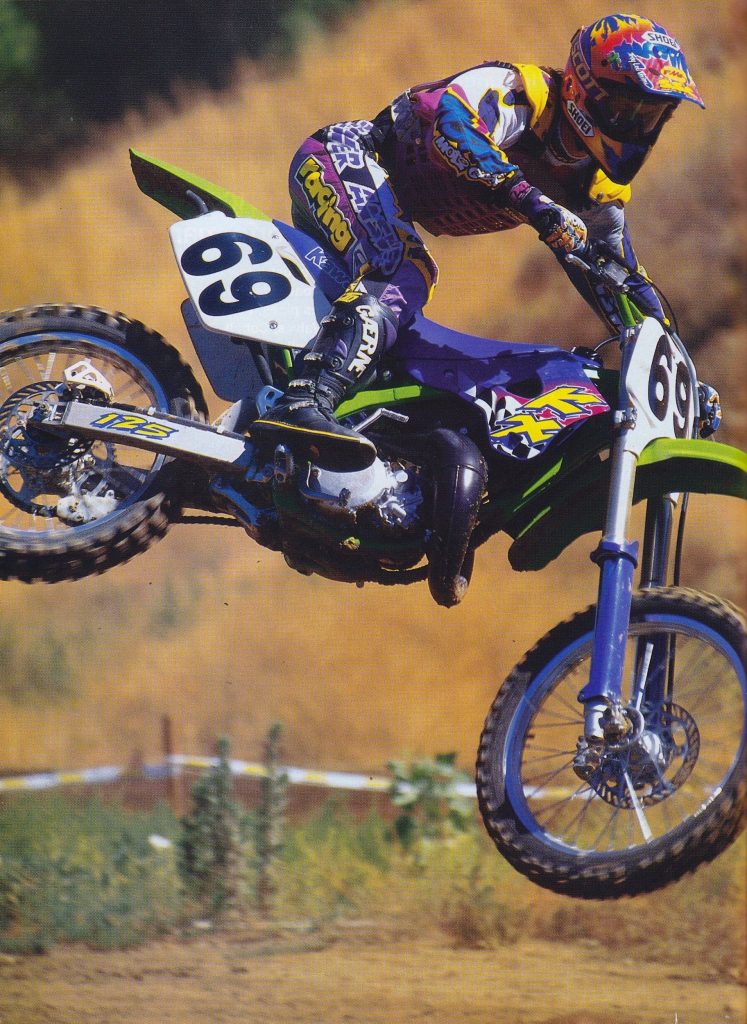

The KX’s hard-hitting midrange motor had the boost to make quick work of berms in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The KX’s hard-hitting midrange motor had the boost to make quick work of berms in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

All-new in 1994, the KX’s steel perimeter frame remained the most unique chassis in motocross. Its perimeter construction provided the KX with a sturdy feel, but it also made the machine larger and wider than its 125 competition. Big and tall riders appreciated the KX’s plus-sized dimensions but not everyone gelled with its 250-like feel. For 1996, the KX’s frame remained unchanged aside from the additional bracing around the swingarm pivot. This combined with the sturdier forks was claimed to greatly improve the KX’s overall handling and steering feel. The KX’s front brakes were also upgraded using a 60mm shorter front hydraulic line and a new front master cylinder. An additional benefit of the new master cylinder was a convenient sight glass built in to allow for quick fluid inspections. In the rear, a new stronger brake pedal was added to reduce flex and improve braking feel.

A revised Uni-Trak linkage for 1996 aimed to smooth out the ’95 KX’s overly stiff action. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

A revised Uni-Trak linkage for 1996 aimed to smooth out the ’95 KX’s overly stiff action. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

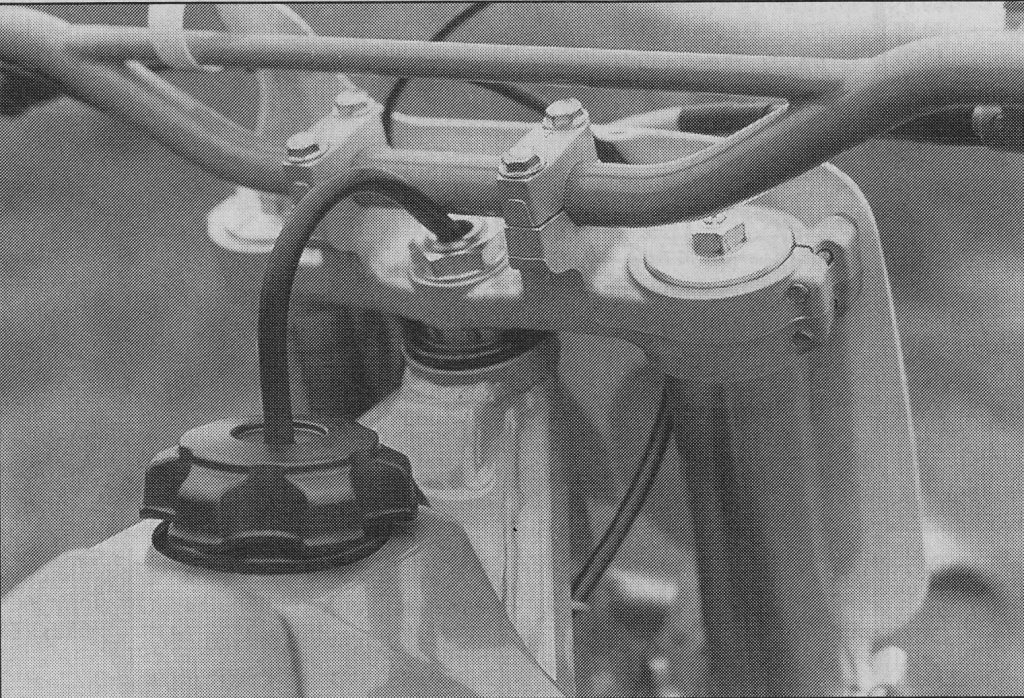

Cosmetically, the KX’s bodywork was radically updated for 1996, but those changes were largely color related. The radiator shrouds, seat, and lower fork guards were moved to a bright shade of purple and these changes were of the love-it or hate-it variety. Purple was all the rage in the early to mid-nineties but most people at the time seemed to think was a bit too far down the purple craze rabbit hole. Thankfully, the change was easy to rectify on the KX125 and KX250 as most of the bodywork was unchanged aside from color. Other than the palette swap, the only significant changes to the KX’s bodywork were a sleek new front numberplate, a new more durable dual-density foam for the seat, and a redesigned gas cap designed to prevent leaks.

Kawasaki’s top gun on the KX125 in 1996 was France’s Mickaël Pichon. His back-to-back 125 Supercross titles continued the winning ways of Mitch Payton and his Pro Circuit race team. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Kawasaki’s top gun on the KX125 in 1996 was France’s Mickaël Pichon. His back-to-back 125 Supercross titles continued the winning ways of Mitch Payton and his Pro Circuit race team. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

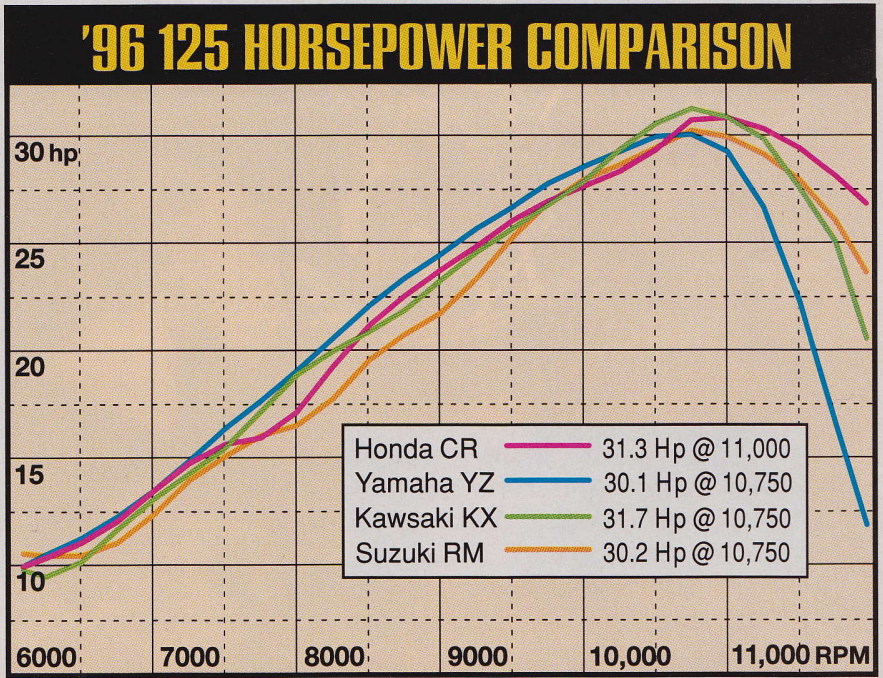

On the track, the KX125 had a lot going for it in 1996. The new motor was snappy and quick with lots of burst to launch the purple machine out of turns and over obstacles. On top, it lacked the rev of high-RPM screamers like the CR, but it was competitive as long as you shifted early and kept it in the meat of its powerband. If you tried to leave the KX pinned then the competition was going to gobble you up, but if you kept it on the bubble, the purple machine had a fighting chance of staying at the front. At 31.7 horsepower, the Kawasaki pumped out the most horsepower in the class on Dirt Bike’s dyno, but everyone agreed it was not the most potent-feeling on the track. There also seemed to be a noticeable discrepancy in the way different KXs ran. Dirt Bike’s test unit was notably faster than MXA’s “identical” test bike and more than a few KXs suffered expensive failures due to improperly finished cylinders. This seemed to be traced back to improper chamfering of the ports and excess flashing inside the cylinder on some units. In all cases, it was best to tear your KX125 down and have the cylinder cleaned up and blueprinted if you wanted to have the best performance and prevent a potentially expensive failure.

The motor changes for 1996 added a bit of breadth to the KX’s power spread but it remained largely a midrange-focused power plant. In the right hands, it was competitive, but it took skill to make the most of its short and punchy delivery. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The motor changes for 1996 added a bit of breadth to the KX’s power spread but it remained largely a midrange-focused power plant. In the right hands, it was competitive, but it took skill to make the most of its short and punchy delivery. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The dyno chart placed the KX at the top of the horsepower wars in 1996, but on the track, most riders felt the broad powerband of the Yamaha and endless pull of the Honda were superior. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Once cleaned up, the KX’s burst motor was quick, but not remarkably fast in the traditional 125 sense. Pinning it to the stops and leaving it on until the cows came home yielded diminishing results so the best tactic was to shift early and often. Thankfully, changes made to the transmission for ‘96 made this easier than in the past and the KX provided a positive, if not particularly smooth shifting action. The new gearing worked well in most situations, but many riders felt the KX’s punchy powerband worked better by adding a tooth to the rear sprocket. This helped the KX get into the meat of its powerband earlier and use its longer-pulling third gear more often. The clutch pull was light, and the unit proved durable under normal abuse. Overall, the KX’s motor package was fun to ride and capable of winning, but certainly not for everyone. Experts lamented its lack of top end and novices often found its short powerband frustrating. The quality and reliability issues were also a pain, but once they were addressed the KX125 offered a competitive motor package.

The KX’s all-new 46mm forks were set up a bit soft for hard chargers but most riders rated them as the second-best units in the 1996 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The KX’s all-new 46mm forks were set up a bit soft for hard chargers but most riders rated them as the second-best units in the 1996 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While a bit larger-feeling than most 125s, the KX was a comfortable and capable flyer in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While a bit larger-feeling than most 125s, the KX was a comfortable and capable flyer in 1996. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the suspension front, the KX was a bit mixed bag in 1996. Up front, the new forks were plush in most situations and well-damped overall. Soft springs and plush damping provided a ride that absorbed small chop and braking bumps almost as well as on the RM’s amazing Showa conventional units. Big hits were taken well but the KYBs could be bottomed fairly easily if pushed. For fast guys, the stock springs and settings were too soft, but most riders rated the KX’s new 46mm legs as some of the best available in 1996.

Factory Kawasaki’s Damon Huffman made the step back down to the 125 class outdoors in 1996 and took his KX125 to a season’s best third place at Troy and Steel City. Photo Credit: AXO Sport

Factory Kawasaki’s Damon Huffman made the step back down to the 125 class outdoors in 1996 and took his KX125 to a season’s best third place at Troy and Steel City. Photo Credit: AXO Sport

Out back, the story was a bit different. Unlike the forks, the KX’s shock was set up very stiffly and this upset both the KX’s handling and suspension performance. Under acceleration, the shock refused to compress, and this made it difficult to get the rear to hook up if the track was slick and rough. Instead of following the terrain, the rear wheel skipped and hopped as the punchy motor clawed for traction. Big hits and large whoops were taken in stride, but the stiff shock felt utterly out of step with the soft settings up front. In stock condition, the rear of the machine felt high and the front felt low, leading to a “stinkbug” stance that upset the machine’s balance. The stiff shock prevented the rear from properly taking a set in turns and put too much of the bike’s weight on the front. This led to headshake at speed and unpredictability at turn-in. To get the best performance out of the KX’s handling it was critical to address this suspension imbalance. If you were a hard charger or planning to race Supercross then stiffening up the forks was a must, but most average riders were likely to be happier with a revalve of the shock to get some compliance back into it.

The KX’s biggest handicap in 1996 was the performance of its rear shock. Overly stiff and uncompliant, it refused to hook up under acceleration and upset the chassis’s balance in the turns. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The KX’s biggest handicap in 1996 was the performance of its rear shock. Overly stiff and uncompliant, it refused to hook up under acceleration and upset the chassis’s balance in the turns. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Once the shock was sorted and the bike was leveled out, the KX was an admirable overall handler. Turning was less precise than its rivals but it could hold the inside line with a bit of effort. Stability was good in most situations and the KX jumped well and tracked straight. The bike felt larger overall than some of its rivals, but it was far from a big and heavy-feeling machine. The stout perimeter frame and large forks gave the bike a solid feel in the rough and the bike rarely stepped out of line or did anything unexpectedly. Testers found that the KX’s chassis was very sensitive to fork height so playing with that was also a way to dial in the Kawasaki’s handling.

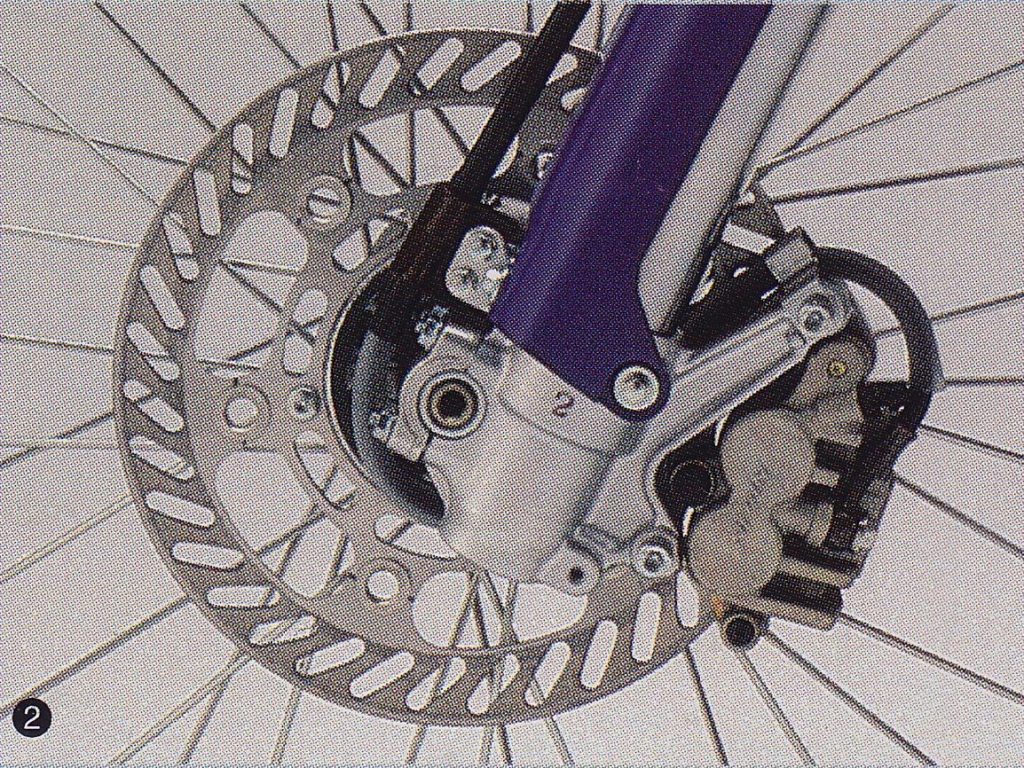

A shorter hydraulic line and a revamped master cylinder improved the KX’s front braking performance for 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

A shorter hydraulic line and a revamped master cylinder improved the KX’s front braking performance for 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After a decade of leaking and cracking gas caps the Kawasaki finally stopped the fuel drool in 1996. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

After a decade of leaking and cracking gas caps the Kawasaki finally stopped the fuel drool in 1996. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

On the detailing front, the 1996 KX125 was improved but far from flawless. In addition to the cylinder issues, the KX suffered from stress cracks in the lower cradle of the frame and around the footpeg mounting. If you were a hard rider additional gusseting in these areas was advisable. Once the cylinder was cleaned up, the KX’s motor was largely reliable, and it no longer tried to blow itself to pieces when fed pump gas – this was a major improvement over previous KX125s which demanded race gas to stave off detonation. The chain rollers also tended to be rather flimsy and smart riders swapped them out for the sealed bearing units found on the CR125. The new gas cap sealed much better and leaks were finally a thing of the past for Kawasaki owners. Braking performance was improved for 1996 but it remained several steps behind the competition. The power, feel, and reliability of the KX’s binders were disappointing in comparison to its rivals and no one cared for the KX’s constant need for bleeding. The steel bars, flimsy chain, and buttery soft sprockets were all par for the course in 1996 and the KX was no better or worse than its Japanese competition. Fastener quality, however, was most definitely below the grade found on the CR and care had to be taken not to strip or damage the various nuts and bolts that held the KX together. The purple plastic was certainly not a unanimous hit, but at least it was easy to swap out, unlike the KX500 and minis which had to deal with a purple tank in addition to the radiator shrouds and fork guards.

In 1996, all-new machines from Yamaha and Suzuki garnered most of the fanfare in the 125 division. The three-year-old offerings from Kawasaki and Honda had their devotees but most pit pundits had the yellow and blue machines as the picks of the litter. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1996, all-new machines from Yamaha and Suzuki garnered most of the fanfare in the 125 division. The three-year-old offerings from Kawasaki and Honda had their devotees but most pit pundits had the yellow and blue machines as the picks of the litter. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the end, the 1996 Kawasaki KX125 turned out to be a competitive if somewhat flawed package. Its rock-hard shock and narrow powerband held it back from defeating more well-rounded packages like Yamaha’s all-new YZ125. With the right pilot aboard and with some fine-tuning it was capable of winning at the highest level, but in stock condition, it was too unbalanced, too pipey, and too unrefined to out-muscle its rivals for the top 125 in the land.

With some suspension tuning and a fast left foot the boldly-styled KX125 could beat anything on the track, but there were easier ways to go fast in the 125 class in 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

With some suspension tuning and a fast left foot the boldly-styled KX125 could beat anything on the track, but there were easier ways to go fast in the 125 class in 1996. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For your daily dose of classic moto goodness give me a follow of Instagram and Twitter – @tonyblazier