For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at the 1980 Can-Am 250 MX-6.

Picked by Motocross Action as one of the ten worst bikes of all time, the 1980 Can-Am MX-6 had some serious issues. Once known for their rocket motors and scary handling, the late seventies Can-Am’s lost their horsepower advantage while maintaining their handling reputation. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Picked by Motocross Action as one of the ten worst bikes of all time, the 1980 Can-Am MX-6 had some serious issues. Once known for their rocket motors and scary handling, the late seventies Can-Am’s lost their horsepower advantage while maintaining their handling reputation. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Today, Can-Am is known mostly as a producer of high-end ATVs and street bikes. Once upon a time, however, the Canadian manufacturer was known as a motocross powerhouse. In the mid-seventies, riding a Can-Am meant you were on the fastest bike available in the 250 class. The Rotax-powered rockets took numerous wins with riders like Gary Jones, Jimmy Ellis and Marty Tripes at the controls. Unfortunately, however, that success was short-lived. After racing to the Supercross title in 1975, Can-Am’s fortunes steadily declined throughout the remainder of the decade. By the time the MX-6 made its debut in 1980, the Canadian-built machines had fallen woefully behind their Japanese and European competitors.

In the mid-seventies, the Can-Am’s Rotax motor was the horsepower king of the 250 class. By 1980, however, Japanese innovation had closed the gap on the Austrian-built power plants. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Can-Am Motorcycles were actually a division of Canadian industrial giant Bombardier. Bombardier was a producer everything from snowmobiles to airplanes and in the early seventies, they were looking to capitalize on the exploding off-road market in America. Bombardier believed they could leverage their highly-regarded Rotax motors (Bombardier had bought Austrian motor manufacturer Rotax in 1970) and extensive snowmobile dealer network to break into the motocross market. In 1973, Can-Am was born with a new off-road machine called the MX-1. The next year, Can-Am lured the reigning 250 National Champion Gary Jones away from Honda to campaign their new machine. To say the new motocross team was a success, would be a massive understatement. With Jones piloting the new machine, Can-AM captured the 1974 250 National Motocross title (technically, Dutch-born Pierre Karsmakers actually won that title, but the AMA had a rule in ’74 that prevented foreign-born riders from winning the championship) from winning the title in ’74) and swept the top three spots in the final standings.

The brakes on the MX-6 were notoriously bad even for the time. Tony D stated that even on his factory bike the brakes would heat up and go away completely after fifteen minutes of hard use. Brake fade was a huge problem on the drum brakes of this era. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The brakes on the MX-6 were notoriously bad even for the time. Tony D stated that even on his factory bike the brakes would heat up and go away completely after fifteen minutes of hard use. Brake fade was a huge problem on the drum brakes of this era. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Can-Am expanded their off-road line in ’75, bringing out four new machines. Unfortunately, however, the dream team of Ellis, Jones, and Tripes would not last. In 1975, Jones would leave Can-Am to start his own motorcycle company (AMMEX), and Marty Tripes would be let go after an off-the-track incident. Luckily for Can-Am, Ellis would prove more than capable of representing the fledgling brand. In 1975, Jimmy would bring home Can-Am’s second title in two-years by winning the 250 Supercross title. That made two major titles in two years for Can-Am. With all that success, it was hard not to think Can-Am was on the way to becoming a serious motocross power.

The 1980 MX-6 models came equipped with 38mm Marzocchi magnesium front forks. These undersized units were flexy, badly overdamped, and pretty much terrible at handling track obstacles. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The 1980 MX-6 models came equipped with 38mm Marzocchi magnesium front forks. These undersized units were flexy, badly overdamped, and pretty much terrible at handling track obstacles. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

After this early success, however, the pace of change started to catch up to Can-Am. Every year, the Japanese relentlessly pushed the pace of innovation forward. Massive racing budgets, intense competitiveness and a willingness to innovate gave the Japanese a huge advantage that their less well-funded and more conservative competition had a hard time matching. As the Japanese pulled farther ahead, less agile companies like Can-Am fell farther behind.

In the early days of two-strokes, rotary-valves offered the most effective way to get serious power from a two-stroke. Eventually, packaging concerns and improvements in reed-valve technology would see the rotary-valve fall from favor. Photo Credit: Can-Am

By the time Can-Am introduced their MX-6 line they were already fighting an uphill battle for respectability. They lacked the Old World reputation of the Euro brands and technological sophistication of the Japanese. The MX-6 was not up to turning the tide for the struggling brand. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In an attempt to keep up with the competition, Can-Am introduced their all-new orange MX-4 series in 1978. The MX-4 featured new plastic, a new frame, a set of 38mm magnesium forks and a pair of Gas Girlings shocks. The new MX-4 continued to use a rotary-valve Rotax motor for motivation. Once the most powerful motor in the class, this Austrian mill was beginning to lose its lead in performance by ’78. Improvements in reed-valve technology and ongoing innovation from the Japanese were quickly eclipsing the performance of the Rotax mills. With its smooth powerband and notchy transmission, it was still relatively competitive, but certainly no longer an advantage.

Unfortunately, not too many people were being won over by the MX-6’s Canadian charms in 1980. Photo Credit: Can-Am

By far biggest problem with the MX-6’s powerplant was its recalcitrant transmission. The engagement was incredibly notchy and it was all-but-impossible to shift under power without using a lot of clutch. Even though Rotax motors are generally known for their reliability, many MX-6 riders suffered seizures and problems with broken kickstart gears in 1980.

By far biggest problem with the MX-6’s powerplant was its recalcitrant transmission. The engagement was incredibly notchy and it was all-but-impossible to shift under power without using a lot of clutch. Even though Rotax motors are generally known for their reliability, many MX-6 riders suffered seizures and problems with broken kickstart gears in 1980.

Unfortunately, the new bikes turned out to be too little, too late. The MX-4 and ’79 MX-5 were inferior to their Japanese rivals and just not up to competing at the top levels of racing. In 1979, Can-am did field an impressive team headlined by three-time National champion Tony DiStefano and future two-time champ Donnie “Holeshot” Hansen, but even with such great riders at the controls, the inferior bikes were too much to overcome. At the end of the season, Can-Am would fold its factory motocross effort for good.

Can-Am’s incredible 1-2-3 finish in the 1974 250 National Motocross Championship would be the high-water mark for the brand.

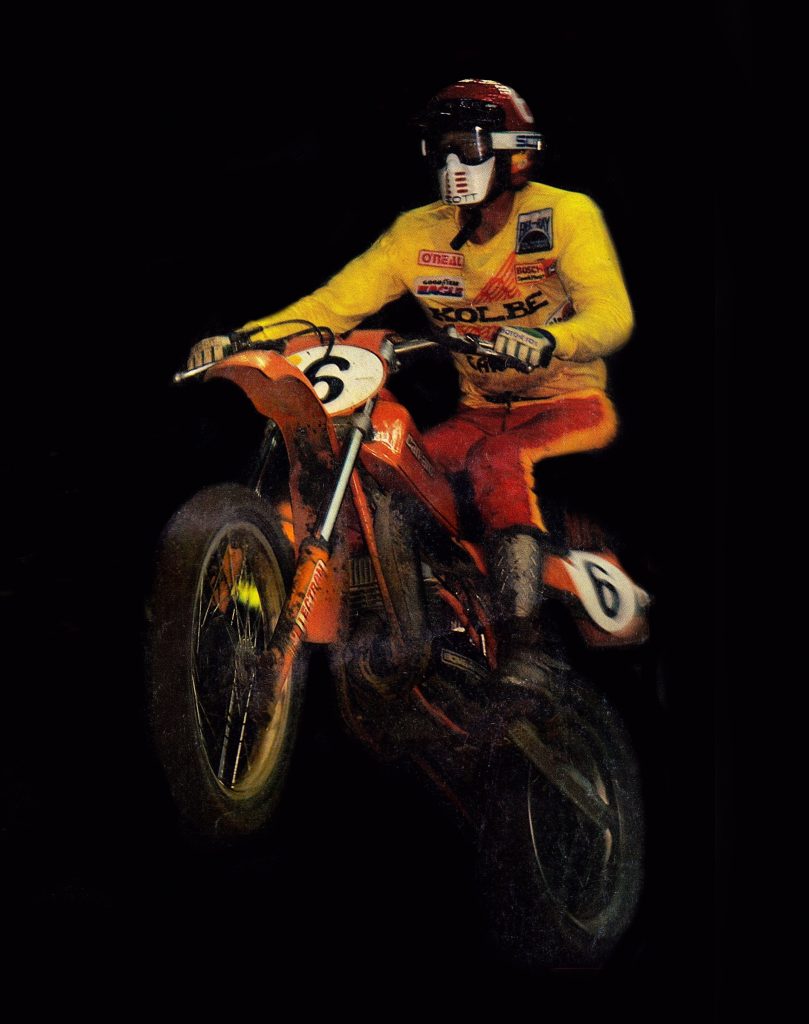

After Can-Am pulled out of professional racing here in the US (they would continue to support riders in Canada, even helping Canadian motocross legend Ross “Rollerball” Pederson at the start of his long career), it was left to California Can-Am dealer Kolbe to keep their racing presence going. Kolbe actually fielded a pretty impressive team on the orange Can-Ams. Leading the team would be long-time Kawasaki ace Jimmy Wienert. He would be joined by Donnie Hansen, Jim “Hollywood” Holley, Jim O’Neal (founder of O’Neal Racing), Eddie Cole and Tom Webb (of Dirt Bike Magazine fame). The team would garner some media exposure due to the presence of Wienert, but fail to score any significant finishes. At the end of the year, Weinert would retire and Hansen would move onto the powerful factory Honda team.

Seventies motocross icon Jimmy Wienert finished out his illustrious career on the Kolbe Can-Am team in 1980. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

Seventies motocross icon Jimmy Wienert finished out his illustrious career on the Kolbe Can-Am team in 1980. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

The air intake on the MX-6 was actually right behind the front number plate. There were two small scoops mounted to the steering head that feed air down through the frame backbone to the airbox. Can-Am claimed the new ram-air intake was good for two horsepower over the ’79 model. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Nineteen eighty-five World Supercross champ Jim Holley would be the last big-name rider to campaign the Can-Ams here in the States. Jim joked that his Can-Am lacked so much ground clearance that the other riders would ask him to go out first in practice and knock down the whoops. Unfortunately, it was not far from the truth. Photo Credit: RacerX Illustrated

Jim Holley would end up being the last major star to campaign the Canadian brand in America. He continued to soldier on with the bikes in Supercross and Motocross well past the point where they were remotely competitive. The motors continued to make decent power but the chassis and suspension were just not up to the rigors of the new jump-filled American tracks. At the end of the ’81 season, Holley would leave Can-Am for Yamaha, effectively ending their motocross racing efforts in America.

There were two options for the rear suspension on the MX-6. The standard shocks were mediocre S&W units, but expensive Ohlins shocks were an optional upgrade. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Can-Am as a Canadian built motorcycle ended two years later with the MX-7 model. After years of trying to make do with inferior designs, Bombardier partnered up with Armstrong/CCM and move production from Canada to England. Unfortunately, that new partnership only lasted four years. While improved, the new white Can-Ams failed to gain any more traction in the market than their orange predecessors had. In 1987, Bombardier shut down the motorcycle division for good and put an end to the Can-Am motocross era.

The MX-6 would be one of the last of the Canadian built Can-Am’s. By 1983 Bombardier would move production to England with partner Armstrong/CCM and launch an all-new line of more modern liquid-cooled machines. The brand would never again catch the lightning in a bottle it had in ’74 and fade out of existence by 1987.

The 1980 MX-6 was one of the last gasps of the original Can-Am motocross era. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com