For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s revamped 1999 RM250.

Redesigned for the 1996 season, the late nineties RM250s enjoyed (endured) an up-and-down relationship with the press and public. For 1999, Suzuki finally brought the firepower the nimble RM’s chassis had been longing for. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Redesigned for the 1996 season, the late nineties RM250s enjoyed (endured) an up-and-down relationship with the press and public. For 1999, Suzuki finally brought the firepower the nimble RM’s chassis had been longing for. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1998 season was a tough one for Suzuki’s motocross faithful. After struggling on the factory RM250 in 1997, Jeremy McGrath moved to blue and immediately resumed his winning ways on the Yamahas in 1998. This black eye for Suzuki only got worse once the magazines got their hands on the production 1998 RM250 and proclaimed it one of the slowest 250s in years. The 1997 RM250 was no powerhouse, but it was a rocket compared to the mild-mannered 1998 machine. The ’98 motor was pleasant and easy to ride, but significantly down on power compared to its rivals. Riders below the Pro class loved the RM’s ultra-plush conventional fork and well-sorted shock, but its lackluster motor left the RM250 at the back of the pack in the 1998 250 standings.

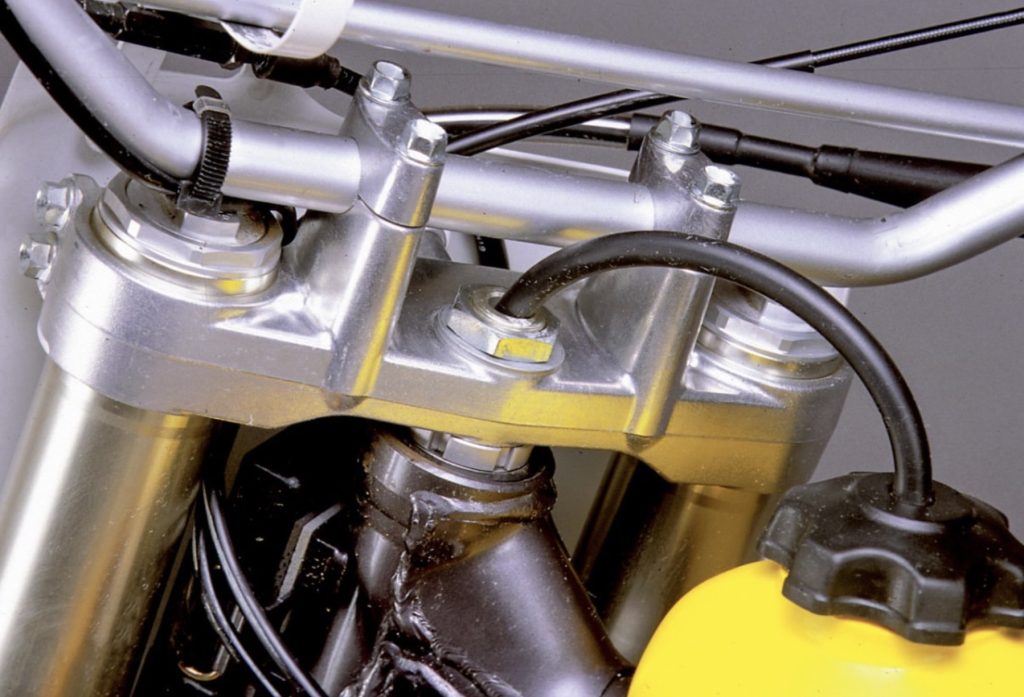

The biggest news in the Suzuki camp for 1999 was the retirement of their publicly praised but pro-pilloried 49mm Showa conventional forks in favor of an all-new inverted Twin-Chamber design. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

The biggest news in the Suzuki camp for 1999 was the retirement of their publicly praised but pro-pilloried 49mm Showa conventional forks in favor of an all-new inverted Twin-Chamber design. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

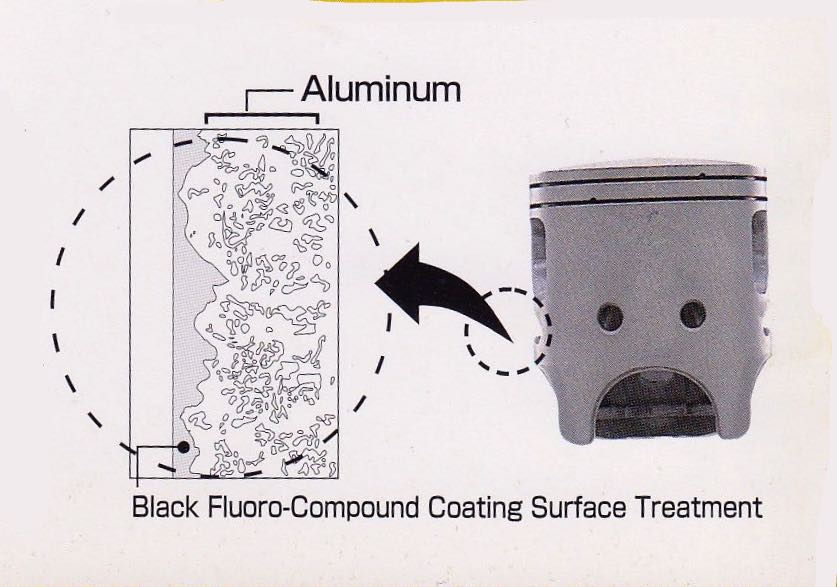

After two years of disappointing showings in the press and on the track, Suzuki was determined to right their 250 fortunes in 1999. First on the glow-up agenda was an all-new motor that looked to return some of the lost BRAAPPPP back to the RM’s arsenal. The new motor retained the cylinder-reed configuration the RM had employed since 1996 and the same 66.4mm x 72mm bore and stroke and 249cc of displacement as in 1998. An all-new cylinder for 1999 featured revamped porting, a revised head, and a significant update to Suzuki’s Automatic Exhaust Timing Control (AETC). An all-new piston for ’99 moved to a domed design from the flat-top used in ’98 and featured a Black Fluoro-Compound coating that Suzuki claimed reduced friction and increased durability.

Maverick approved: Larger radiators for 1999 dictated a redesign of the RM’s previously svelte radiator shrouds into the largest set of ram scoops this side of an F-14 Tomcat. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

Maverick approved: Larger radiators for 1999 dictated a redesign of the RM’s previously svelte radiator shrouds into the largest set of ram scoops this side of an F-14 Tomcat. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

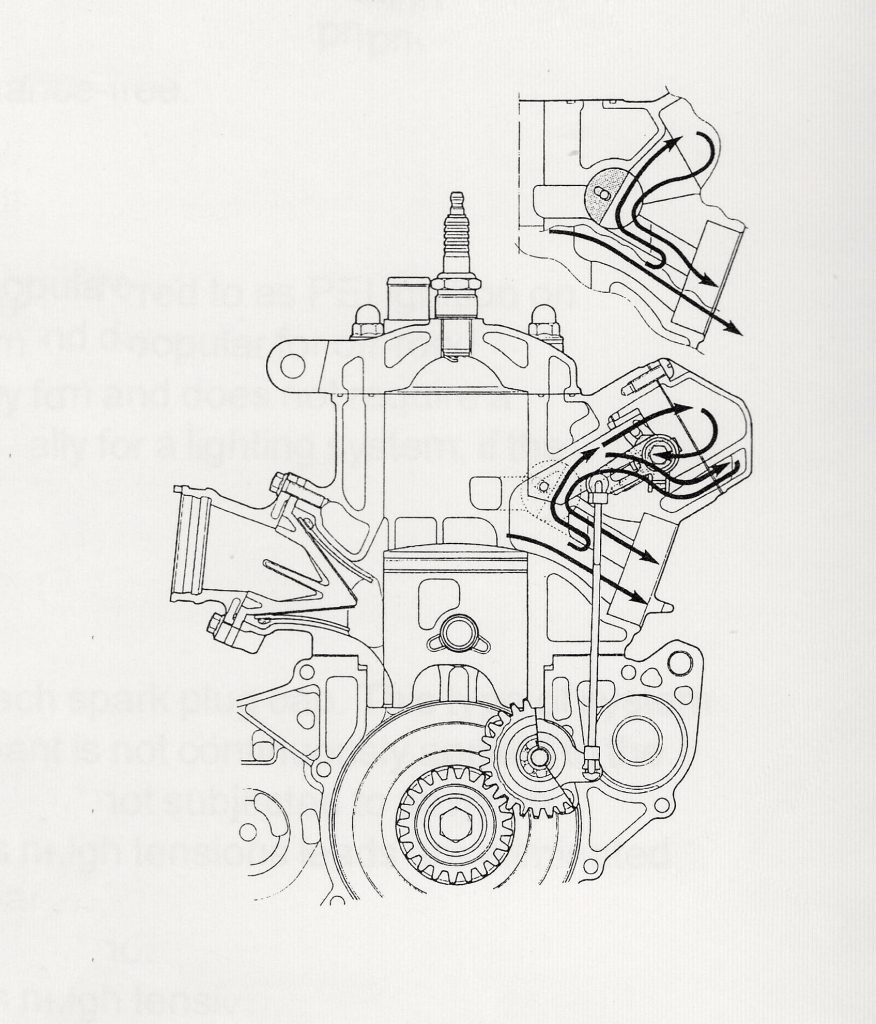

By 1998, virtually all the manufacturers were using some version of Kawasaki’s KIPS-style variable exhaust system that incorporated both a variable exhaust valve and an exhaust resonance chamber. This combination of features was found to offer the most tunability and deliver the widest possible powerband in a high-performance two-stroke single. For 1999, Suzuki jumped on the KIPS bandwagon by modifying their existing AETC design’s mechanical guillotine valves to allow exhaust gases to pass into a small chamber above the valve mechanism at low RPM. Dubbed the “Power Chamber”, this small reservoir boosted head pipe volume at low RPM and allowed Suzuki’s engineers to vary exhaust back pressure to optimize throttle response. In addition to the new exhaust passthrough, the L-shaped linkage for the AETC was also modified to provide more precise control of the valves for improved midrange response.

An all-new cylinder for 1999 added an exhaust resonance chamber to the RM’s power valve system to boost low-end torque and fill out the previous motor’s underwhelming powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

An all-new cylinder for 1999 added an exhaust resonance chamber to the RM’s power valve system to boost low-end torque and fill out the previous motor’s underwhelming powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In addition to the updated cylinder, the new motor featured an increase in the crank’s inertia to improve tractability and revised cases to provide more efficient fuel charging. The 38mm Keihin power-jet carb was retained from 1998, but the power-jet circuit was modified to provide an updated spray pattern for improved mid-to-top-end power. All-new radiators for 1999 bumped up coolant capacity by 10 percent by adding an additional row of cooling veins to each radiator’s core. A new ignition curve was programmed into the CDI to match the all-new porting and revised AETC mechanism. The exhaust system was largely unchanged for 1999, but a new enclosed endcap was added to the silencer to meet the new FIM safety standards being passed in Europe.

A new enclosed tip for the RM’s silencer reduced the chances of the silencer causing injury in a crash and complied with updated safety rules being rolled out by the FIM. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

A new enclosed tip for the RM’s silencer reduced the chances of the silencer causing injury in a crash and complied with updated safety rules being rolled out by the FIM. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

On the chassis front, the most dramatic change in 1999 was the move back to an inverted fork for the front of the RM. In 1996, Suzuki had bucked conventional moto wisdom by ditching their inverted Showa Twin Chamber forks in favor of an all-new 49mm conventional Showa design. These new forks drew rave reviews from the press and public, but never caught on with Suzuki’s factory riders, who found their compliance a hindrance rather than a help. For them, the plush feel the conventional forks provided was far less important than the precision and control the inverted designs delivered. After the factory Suzuki team moved back to inverted forks full-time in 1998, the writing was on the wall for the RM’s press-popular but pro-polarizing front end. By moving back to an inverted design, Suzuki would be able to capitalize on Showa’s development work over their Japanese competitors rather than continuing to go their own way.

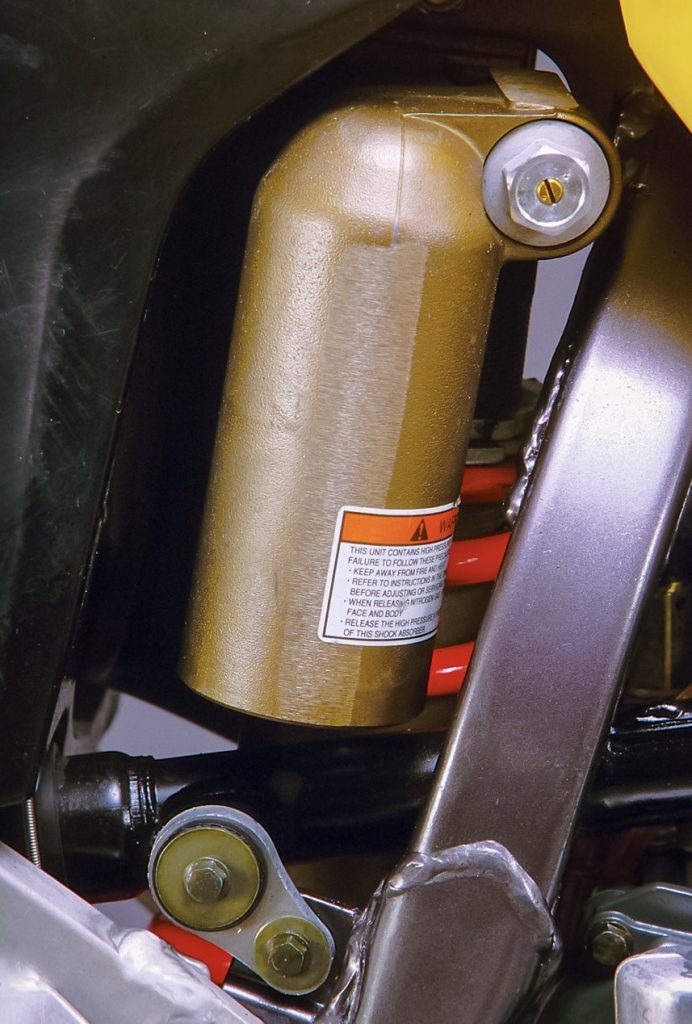

A new progressive-rate spring, revised valving, and increased bracing for the swingarm mounting highlighted the significant changes to the RM’s Full Floater rear suspension in 1999. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the factory team was not a fan of the conventional forks, Suzuki understood they were popular with many average riders. Their super-plush action gobbled up bumps and jumps and delivered the smoothest ride in the class. With the move back to inverted forks, Suzuki’s goal was to keep the comfort of the conventional design while also satisfying the demands of faster riders who craved the increased precision the inverted sliders provided. Up to this point, no manufacturer had been able to nail this elusive combination of conflicting traits, but Suzuki’s PR department claimed to have cracked the code with their revamped 1999 fork design.

The stock RM’s appearance improved greatly by dropping the odd “ROM” decals and adding these slick N-Style factory Suzuki graphics. Interestingly, even Suzuki must have realized these massive shrouds were a mistake, as they would move back to the more attractive and less intrusive 1998 shroud design on their factory machines a year later. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The stock RM’s appearance improved greatly by dropping the odd “ROM” decals and adding these slick N-Style factory Suzuki graphics. Interestingly, even Suzuki must have realized these massive shrouds were a mistake, as they would move back to the more attractive and less intrusive 1998 shroud design on their factory machines a year later. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Suzuki claimed that they captured the best traits of both designs by redesigning the bushings to reduce friction and carefully balancing the mix of materials and wall thicknesses of the tubes. The new inverted forks remained a Showa design, with stanchions that measured 49mm in diameter. Internally, the new fork retained Showa’s successful Twin Chamber cartridge system that separated the suspension fluid from the air within the fork to prevent aeration and frothing of the fluid. This allowed the fork to provide precise damping control and more consistent action. The new fork was 0.5 pounds lighter than the old design, with reduced underhang below the front axle and 31.0mm more travel. The revamped fork maxed out at 12.2 inches of travel and featured 16 external adjustments for compression and rebound damping.

A new “Black Fluoro-Compound” coating was added to the 1999 RM250’s piston to reduce friction and increase durability. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new “Black Fluoro-Compound” coating was added to the 1999 RM250’s piston to reduce friction and increase durability. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the rear, the RM’s Full Floater was only mildly revamped for 1999. The linkage retained the same ratio as 1998, but additional reinforcements were added to the swingarm pivot to reduce flex under heavy suspension loads. The shock was once again designed and built by Showa with updated valving and a move to a progressive-rate spring. Suzuki claimed the new shock valving would provide smoother action from initial movement to mid-stroke while also delivering improved bottoming resistance at full compression. Rear wheel travel remained unchanged from 1998, with 12.4 inches of rear movement. Both compression and rebound damping were externally adjustable with 20 selectable settings for compression and 24 adjustable detents available for rebound control.

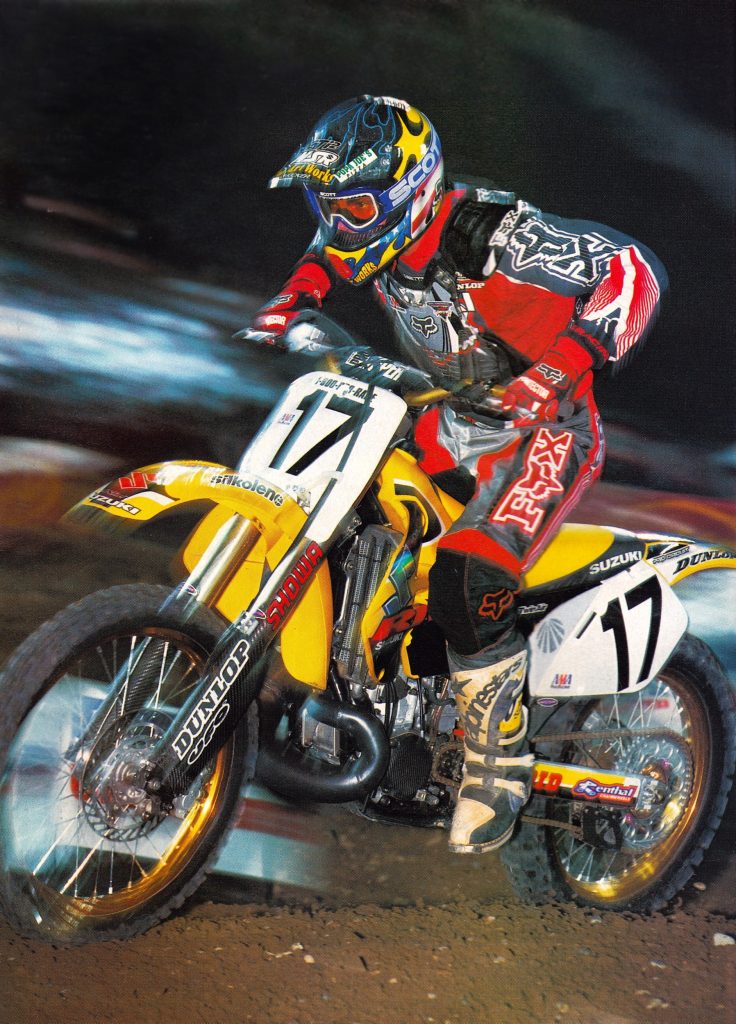

Team Suzuki featured an interesting mix of established veterans and up-and-coming talent on their roster in 1999. Once the most highly-touted rookie in the 125 division, Oklahoma’s Robbie Reynard made the big jump to the premier class on the RM250 in 1999. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Team Suzuki featured an interesting mix of established veterans and up-and-coming talent on their roster in 1999. Once the most highly-touted rookie in the 125 division, Oklahoma’s Robbie Reynard made the big jump to the premier class on the RM250 in 1999. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Frame and geometry changes for 1999 were very minimal, with the reinforced swingarm pivot being the most dramatic change to the RM’s frame. The footpegs and mounts were also repositioned 10mm rearward to open up the pilot’s compartment slightly. Most of the RM’s bodywork was a carryover from 1998, except for a new front number plate to accommodate the move back to inverted forks and a redesign of the radiator shrouds. Interestingly, this turned out to be by far the most controversial change Suzuki made to the RM250 in 1999. Some riders missed the conventional forks, but far more seemed to have opinions about the RM’s gigantic new radiator ram scoops. The new shrouds were twice the size of the old radiator covers, and most riders seemed to feel that they did the RM’s aesthetics no favors. In addition to being rather unattractive, they also splayed out quite prominently at the front and liked to catch on riders’ boots in turns. All-new graphics accompanied the updated bodywork and further complicated the RM’s looks by stretching the “RM” logo across the massive shrouds into an odd design that appeared to spell out “ROM.” Braking performance was upgraded for 1999 with the addition of all-new grippier pads and an increase of 20mm to the diameter of the rear rotor.

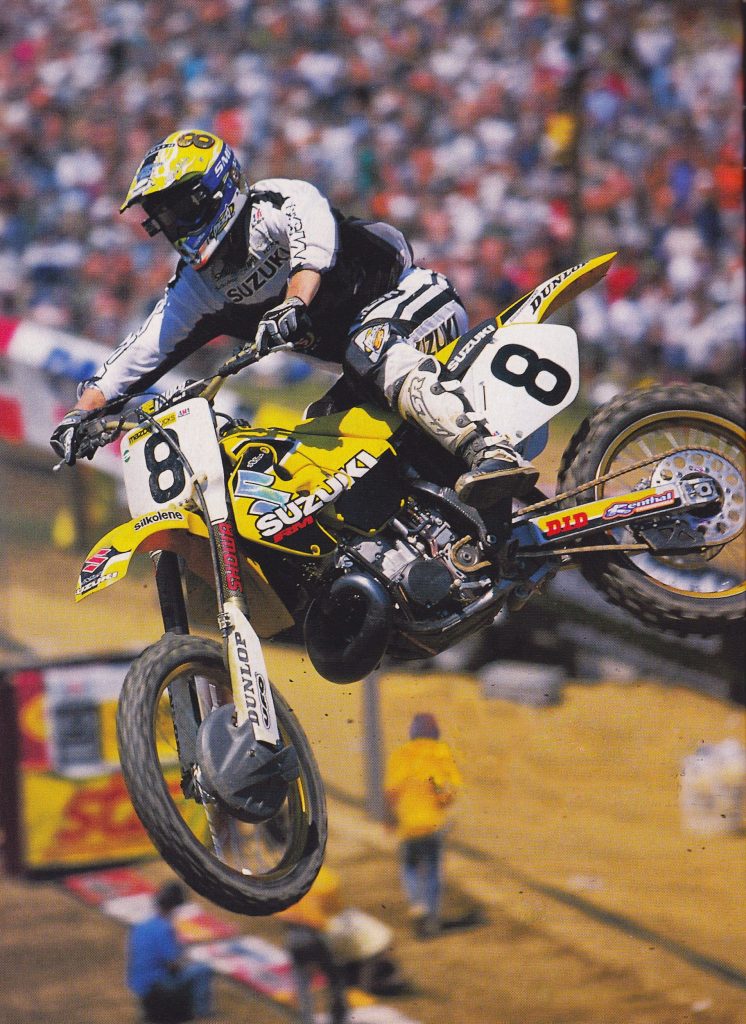

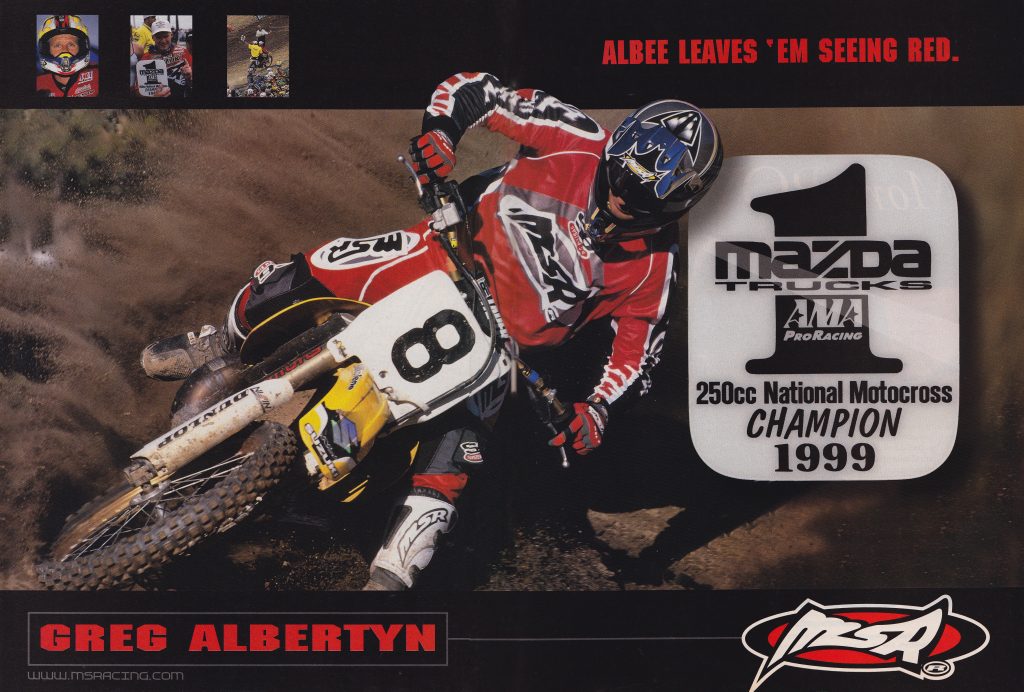

Heading up the Suzuki team for 1999 was three-time World Motocross Champion Greg Albertyn. While Greg had shown improvement over the three previous seasons in the US, capturing several podiums and two victories, his immense European success had proven difficult to replicate on the AMA circuit. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Heading up the Suzuki team for 1999 was three-time World Motocross Champion Greg Albertyn. While Greg had shown improvement over the three previous seasons in the US, capturing several podiums and two victories, his immense European success had proven difficult to replicate on the AMA circuit. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Joining Reynard and Albee on the revamped RM250 in 1999 was Washington’s Larry Ward. After winning the Seattle Supercross on a factory Suzuki in 1990, Larry’s career took quite a circuitous path to end up back with the factory team nearly a decade later. When Ward captured the victory on his RM250 at Tampa in 1998, he set the record for the longest gap between Supercross victories in AMA history. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Joining Reynard and Albee on the revamped RM250 in 1999 was Washington’s Larry Ward. After winning the Seattle Supercross on a factory Suzuki in 1990, Larry’s career took quite a circuitous path to end up back with the factory team nearly a decade later. When Ward captured the victory on his RM250 at Tampa in 1998, he set the record for the longest gap between Supercross victories in AMA history. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the track, the 1999 RM250 was substantially upgraded in the one area that most riders found the 1998 version to be most lacking. The new power valve and updated porting finally put competitive power back in the RM’s arsenal. The updated motor pulled well from the first crack of throttle with a snappy response and quick-revving feel. It was not as chunky out of the hole as Kawasaki’s super-torquey KX, but it was easy to get on the pipe and very responsive to throttle input. The new motor did its best work from midrange on up with a strong hit and lots of pull on top. It was not the fastest motor in the class, but its wide powerband, solid pull, and ultra-responsive delivery made it one of the most fun and effective bikes on the track. Riders of all skill levels praised its improved power and powerband flexibility. Overall, it was easily the most improved motor in the 1999 250 motocross division.

The RM’s revamped motor for 1999 finally delivered the kind of power racers had been asking for since the 1996 redesign. Strong off the bottom, hard-hitting in the middle, and long-legged on top, the 249cc mill was an excellent racing motor. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

The RM’s revamped motor for 1999 finally delivered the kind of power racers had been asking for since the 1996 redesign. Strong off the bottom, hard-hitting in the middle, and long-legged on top, the 249cc mill was an excellent racing motor. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

On the suspension front, the new RM was not nearly as successful in 1999. Ironically, however, it was not the new inverted forks that torpedoed Suzuki’s fortunes. Up front, the new 49mm USD forks were praised for their plush feel and smooth action. Fast guys appreciated the reduced flex and generally found the switch to be an improvement. Bottoming could be an issue for riders with pro-level speed, but most riders seemed to find their action and stock settings well sorted. Some riders of lesser speed and skill still missed the silky-smooth action of the old conventional forks, but the switch was not any real impediment to the RM’s effectiveness on the track.

The RM’s new 49mm inverted Showa Twin-Chamber forks were solid performers in most respects. Fast guys appreciated the reduced flex their large stanchions provided, but most of them felt stiffer springs were required to prevent bottoming. For riders of average skill and size, they were well set up and raceable with only some small oil and clicker adjustments. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The RM’s new 49mm inverted Showa Twin-Chamber forks were solid performers in most respects. Fast guys appreciated the reduced flex their large stanchions provided, but most of them felt stiffer springs were required to prevent bottoming. For riders of average skill and size, they were well set up and raceable with only some small oil and clicker adjustments. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Where things went wrong for the RM was in the shock department. In 1998, the RM’s shock was criticized for being too stiff and harsh, so for ’99, Suzuki went the other direction and softened things up considerably. This correction, however, seemed to go a bit too far, with even novice pilots complaining of bottoming and mushy action from the rear damper. The light damping and wimpy rear spring struggled in the chop and gave the rear a very unsettled feel in the rough. Any sort of serious airtime crashed the damper to the stops and painted the rear fender with black streaks of rubber. Riders from beginner to pro panned its subpar performance. By upgrading the rear spring and fiddling with the clickers, the stock shock could be made raceable, but anyone looking to push the limits of the RM’s capabilities was likely to want a revalve.

Ginsu: Over the past ten seasons, razor-sharp turning had become the RM’s stock in trade. In 1999, that glue-like front end and nimble feel continued to be Suzuki’s greatest handling asset. Bumpy high-speed straights were at times harrowing, but when it came time to shred in the twisties, the scalpel-like RM had no peers. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Ginsu: Over the past ten seasons, razor-sharp turning had become the RM’s stock in trade. In 1999, that glue-like front end and nimble feel continued to be Suzuki’s greatest handling asset. Bumpy high-speed straights were at times harrowing, but when it came time to shred in the twisties, the scalpel-like RM had no peers. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After three very up and down seasons, South Africa’s Greg Albertyn finally struck gold in the US by piloting his factory Suzuki RM250 to the 1999 AMA 250 National Motocross championship. Remarkably, this marked the first major AMA 250 title for Suzuki since Mark Barnett and Kent Howerton swept the Motocross and Supercross championships for Yellow Magic in 1981. Photo Credit: MSR

After three very up and down seasons, South Africa’s Greg Albertyn finally struck gold in the US by piloting his factory Suzuki RM250 to the 1999 AMA 250 National Motocross championship. Remarkably, this marked the first major AMA 250 title for Suzuki since Mark Barnett and Kent Howerton swept the Motocross and Supercross championships for Yellow Magic in 1981. Photo Credit: MSR

On the handling front, the RM remained the most aggressive machine in the class. It shredded in the turns and could carve arcs under most other machines on the track, including a few 125s. The new wider radiators were an annoyance to some who complained of catching their boots on the shrouds, but it did little to dampen the RM’s stellar turning manners. The front end stuck like glue on nearly any surface and allowed the Suzuki’s pilot to select lines that most of the other bikes in the class could only dream of. In the air or on the ground, the Suzuki’s chassis was alive and ready to pounce at a moment’s notice.

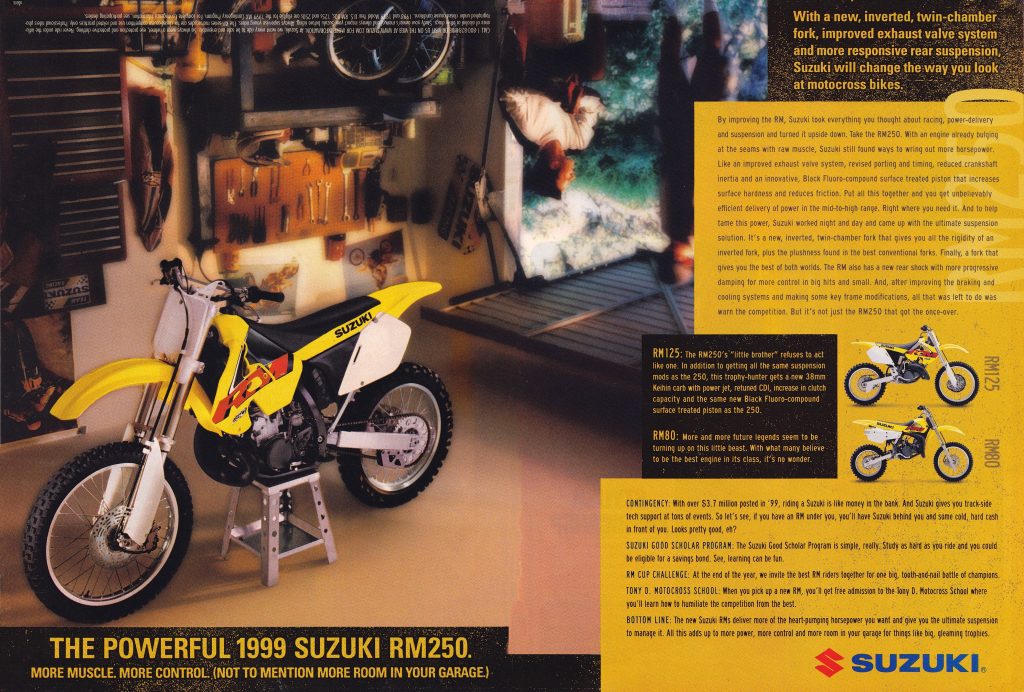

The ad for the new RMs poked a bit of fun at the switch back to inverted forks by displaying the revamped RM250 mounted on the garage roof, Spiderman style. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The ad for the new RMs poked a bit of fun at the switch back to inverted forks by displaying the revamped RM250 mounted on the garage roof, Spiderman style. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the new forks worked well, the updated rear shock turned out to be a disappointing performer. Softly sprung and underdamped, it was prone to bottoming on big hits and hopping in the rough. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the new forks worked well, the updated rear shock turned out to be a disappointing performer. Softly sprung and underdamped, it was prone to bottoming on big hits and hopping in the rough. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Unfortunately, however, the flip side of this cat-like corning quickness continued to be the RM’s utter aversion to the high-speed sections of the track. Here, the Zook was wholly out of its element and a genuine handful. The front end danced in the rough, and the rear hopped and wandered. The poorly set up shock only exacerbated this high-speed schizophrenia, and the RM required strength and more than a bit of bravery to keep from backing down the pace. Longtime Suzuki pilots seemed to accept this tradeoff, but riders jumping on the RM from a Yamaha or Kawasaki often came back muttering about seeing their life pass before their eyes a few times per lap.

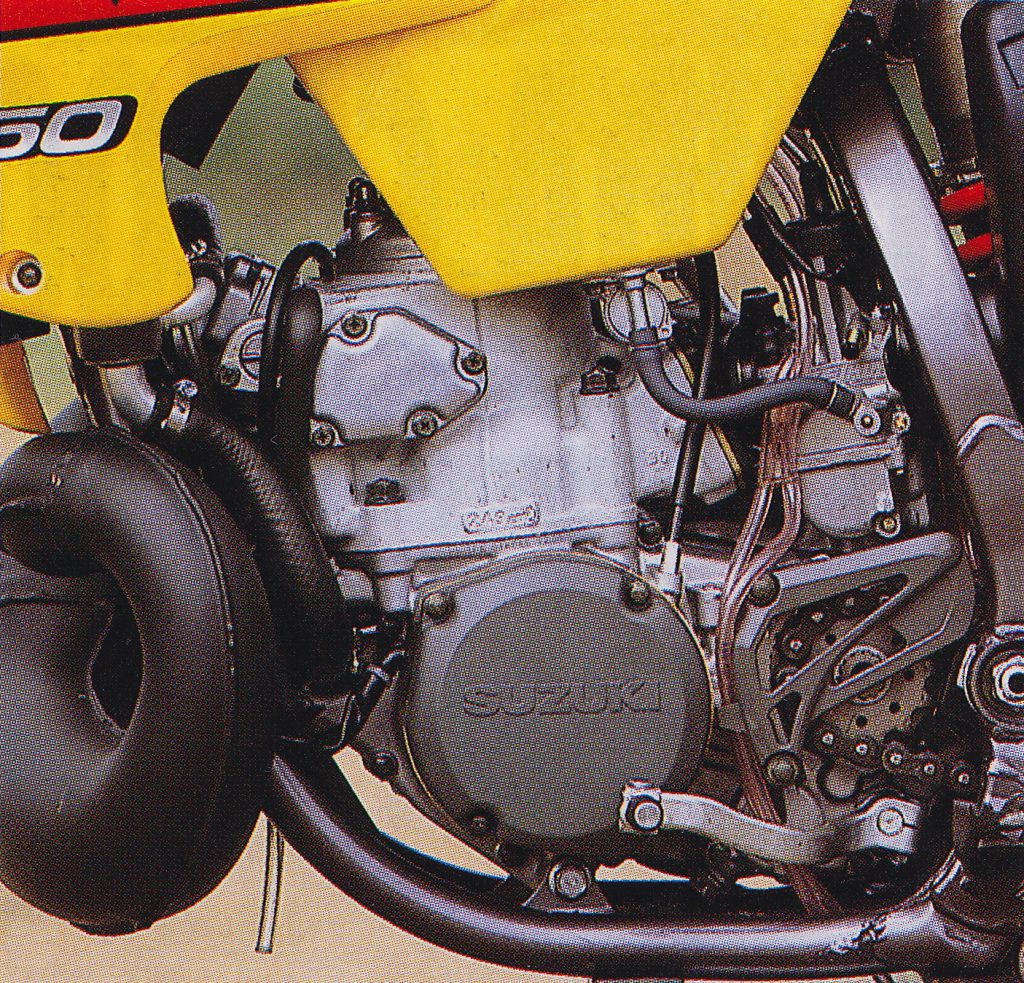

Suzuki’s decision to place the waterpump inside the cases gave the RM’s motor a unique look and protected it from crash damage. The flipside of that decision was more complicated servicing and an odd sound from the bottom end that some found disconcerting. Photo Credit: Unknown

Suzuki’s decision to place the waterpump inside the cases gave the RM’s motor a unique look and protected it from crash damage. The flipside of that decision was more complicated servicing and an odd sound from the bottom end that some found disconcerting. Photo Credit: Unknown

On the detailing front, the RM continued to be largely a disappointment compared to its rivals. Riders loved the light throttle and silky-smooth clutch pull but soured on its action when it became hot and refused to fully disengage. Upgrading to a Hinson or other aftermarket components was a must for riders who liked to hammer the plates. Most riders found the levers comfy, but they tended to get loose and rattly far faster than the competition. Suzukis were traditionally smooth shifters, but manufacturing errors on some RMs left more than a few riders dealing with sticky third gears. Not every RM was afflicted with a cranky cogbox, but for those affected, deburring the dogs was the best fix. The stock grips, chain, and sprockets were junk, and the stock steel bars could be bent without the bike even hitting the ground. Just bottoming out the forks on a hard landing was often enough to leave these buttery tubes drooping like they had melted in the hot sun. The stock ROM graphics were an acquired taste, but you had best acquire them quickly because they tended to jump ship in short order. The RM’s ergonomics were well-liked by most pilots aside from the gargantuan snow shovels Suzuki used for radiator shrouds.

The RM’s stock bars, levers, bolts, and switchgear were a significant step behind the best in the class in 1999. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The trick internal water pump kept the fragile bits out of harm’s way, but it continued to produce a weird rattly sound that made the riders think it was about to blow something out of the cases. This odd note from the motor left many riders feeling as if the RM sounded clapped out, even when new. With its cacophonous motor, rattly levers, expiring graphics, and pot-metal components, the RM felt, looked, and sounded tired more quickly than the other bikes in the class. The bike was not particularly unreliable, but it gave the impression of lower quality to many.

All of the 250s had their virtues, but most magazine editors felt the stock KX and YZ delivered the best out-of-the-crate performance for those looking to collect trophies in 1999. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

All of the 250s had their virtues, but most magazine editors felt the stock KX and YZ delivered the best out-of-the-crate performance for those looking to collect trophies in 1999. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the end, the 1999 Suzuki RM250 turned out to be a much-improved, if still flawed, racer. The updated motor was leaps and bounds better than in 1998, and this alone was enough to lift the RM in the final standings. The new inverted forks lacked some of the old conventional unit’s plushness, but most racers found they were more than good enough to get the job done. The RM’s excellent turning, light feel, and powerful motor provided a solid base from which to build a great racer, but its poor stock shock needed to be sorted if you were looking to get the most out of its nimble chassis. With a revalved shock, an upgraded clutch, and some aftermarket bars, the RM became a real threat to take home that coveted piece of gold plastic for the mantel. It was never going to be the tightest-feeling or best-finished bike in the class, but if you loved lots of hit and coveted the inside line, the RM250 had your cravings covered in 1999.

Fast, nimble, and fun to ride, the Suzuki RM250 was a much-improved machine in 1999. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

Fast, nimble, and fun to ride, the Suzuki RM250 was a much-improved machine in 1999. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata