For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of Honda’s most iconic motorcycles, the original “Red Rooster” ‘78 CR250R Elsinore.

By: Tony Blazier

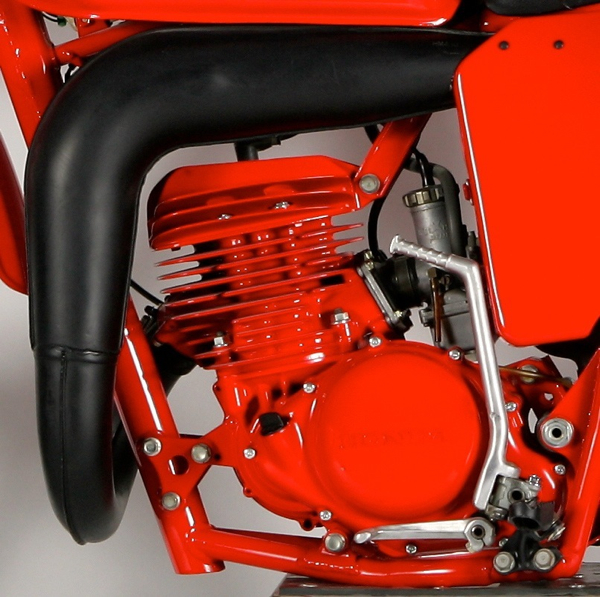

This bike screamed performance from every inch of its fire engine red bodywork. Looking for all the world like a ’77 works RC500, the all-new CR250 “R” was a quantum leap forward for Honda. Featuring nearly a foot of travel front and rear, and equipped with an absolute rocket of a motor, the new Elsinore was one serious race machine. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1973, Honda stood the collective motocross community on its ear with its groundbreaking CR250M Elsinore. The CR was Honda’s first production two-stroke and a real revelation at the time. It offered power, handling and suspension performance that was unheard of up to that point. All at a price, the average Joe could afford. Honda had caught lightning in a bottle with the original Elsinore, and it raked in the sales while the competition played catch up. Unfortunately, Honda’s lead would be short-lived. Within two years of the CR250M’s debut, all the Big Four would have credible alternatives available to the public. Even worse for Honda, in most cases, those competitors were quickly leaving the CR in their dust.

By 1976, the CR250 was already falling far behind its 250 competition. Major suspension upgraded on the RM and YZ left the short-legged CR in their wake. Thankfully, there was an all-new CR250 on the horizon. Photo Credit: Honda

With the introduction of Yamaha’s revolutionary Monoshock YZ and Suzuki’s excellent RM250, Honda was left playing catch up in the years after the CR250M’s debut. While the competition iterated at breakneck speeds, Honda kept turning out the same old ’73 CR with minor updates. By 1977, the disparity in performance between the CR and its competition was becoming laughable. If Honda was going to remain a player in the hotly-contested 250 class, it was going to have to come out with a hot new machine to woo buyers back into the their showrooms.

|

| The heart of the Red Rocket was its advanced 247cc powerplant. Borrowing heavily from the RC Type II works racers, the new CR motor was all business, right down to its GP inspired left-hand kick and ultra-compact dimensions. Using a works-style cylinder and six-pedal reed-valve induction, the CR produced a hard-hitting pro-oriented style of power. Soft off the line, the CR really hit its stride in the mid-range, where it pulled with ferocity into a screaming top-end blast. Too much for most novices, the Elsinore was fast enough to outrun most other brand’s modified machines. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

From ’73 to ’77, while Honda was busy slapping “Bold New Graphics” on their production bikes, the race team was fast at work cranking out super trick factory racers. These RC race bikes shared absolutely no connection to the lackluster production machines, and in some cases did not even have a production equivalent (Honda would race works 500’s for years before actually producing one for the public). These bikes were handmade and in a constant state of flux, with the teams always looking to gain an edge on the competition. Perhaps the most famous of these seventies works Honda’s was the 1976 RC500 Type II. The Type II was a revelation at the time, featuring long travel suspension at both ends, (and one of the first applications of Showa’s cartridge fork internals 10 years before it would see production) excellent handling and a rocket of a motor. The Type II was light years ahead of anything Honda was building at the time, and it would provide the inspiration for Honda’s all new ’78 CR250R (the “R” was said to stand for Type II “replica”).

|

| In 1976 Honda dropped another bombshell on the motocross world with their incredible RC500M Type II racer. The first of Honda’s long travel works bikes, the Type II set new standards for performance on the GP scene. This ’77 version of the Type II, ridden by Brad Lackey and currently owned by collector Terry Good, served as the blueprint for the all-new ’78 CR250R works replica. Aside from the bigger 398cc motor and the Fox Airshox, the production Elsinore was the spitting image of the mega-bucks factory racer. Photo Credit: Terry Good |

When you look at the ’78 CR250R Elsinore it is certainly not hard to see the family resemblance to the RC works Hondas. Everything on the bike is coated in that lustrous fire engine red paint that the works bikes were known for. Even the tank and bodywork looks to have been taken right of Lackey’s RC500. If that screaming red engine was not enough to signal this was a new type of CR, one look at that massive suspension travel certainly sealed the deal. The new CR250R featured by far the most suspension action of any bike available in ’78. At nearly a foot of travel front and rear, it towered over its predecessor. This definitely was an all-new kind of Elsinore.

In 1978 these were the longest-travel forks in motocross. Coming in at nearly a full foot of suspension travel, they offered nearly three inches more movement than any of the CR’s competition. The non-adjustable 37mm Showa’s were considered decent at the time, offering good compliance on small and medium hits. Off big jumps or on large jumps, they were too soft and could be bottomed easily. In addition to being too soft initially, the stock springs tended to sag out very quickly and give the bike a stinkbug stance. The aftermarket was quick to come out with spring kits, re-valves, and air caps to sort out the Elsinore’s front end. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The ’78 CR250R Elsinore was an all-new design from the ground up. It featured a new frame, motor, and bodywork to go with its remarkable suspension. The heart of the new CR was its 247cc air-cooled two-stroke single. The Red Rocket’s motor was works inspired just like the rest of the machine. It featured a unique internal design with two auxiliary scavenging ports that simulated a case-reed intake and allowed a fully skirted piston to be used for durability. The intake itself used a six-pedal reed-valve, fed by a 36mm Keihin round-slide carburetor. The cylinder featured a chrome bore (non-borable), which dissipated heat better than the traditional iron liner. It was also was lighter and allowed Honda to use smaller fins on the cylinder. The rest of the motor was very compact, with cases tightly formed to the mechanical internals and no wasted space. Components like the as the shifter and kickstarter were made of lightweight aluminum instead of the more common steel to further trim weigh. All told, the new motor came in at a remarkable 56 pounds.

|

| The CR250R’s motor was incredibly compact and lightweight. Again, borrowing from the design of their RC racers, all the cases were virtually vacuum formed over the motor’s internals. With the extensive use of magnesium and aluminum, the 247cc motor was kept to just 56 lbs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

Honda claimed 36hp at the time for the new CR250R, which was a considerable amount in 1978 (many 500’s at the time could not crack 40hp on the dyno). The real number was closer to 30hp when the bike was dyno’d by many magazines at the time, but that was still a considerable amount for a 250 of this era. On the track, the Red Rocket was just that, a rocket. Low-end power was very soft but once the “R” reached the mid-range, hold on! Horsepower and torque more than doubled in the 1000-rpm span between 4000 and 5000 rpm. The mid-range was explosive and followed by a shrieking top-end pull all the way to its 8500-rpm redline. The CR’s powerband closely followed the power curve of the RM250B, but bested it at every point. The motor was so potent, that the only real complaint heard about it was that it was too much for less experienced riders to handle. The midrange was so explosive that the bike gained a reputation for being very easy to loop out (a fact I can attest to as mine was looped out on three separate occasions by friends I let take it for a ride). The “R” was no play bike, it was a serious bike made to do one thing, win races.

|

| The use of lightweight components factored into every inch of the new Elsinore. The backing plates for the excellent front and rear brakes, as well as the ignition cover, were all crafted from magnesium. The tank, shifter, and kickstarter were all manufactured out of featherweight aluminum. With these features and all the weight saving tricks used in the motor, the CR250R tipped the scales at a mere 218 lbs. That was significantly less than the CR’s competition and remarkable in light of the bike’s additional size. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

As much as the ‘78’s ripping motor was a big deal, it paled in comparison to the fervor over the R’s extreme suspension. While class leaders Yamaha and Suzuki were delivering bikes that had around 9 inches of suspension front and back, the new Honda leap-frogged them with 11-inches of travel in the rear and a jaw-dropping full foot of travel up front. These super long travel Showa forks used 37mm stanchion tubes and offered no external adjustability. Performance wise, the front forks were considered pretty good for the time. They offered good compliance on the small stuff, but bottomed badly when pushed. With no adjustability built in, the aftermarket went wild offering spring kits, air caps and revalved internals for the red machine.

|

| Starting in ’73, all Honda CRs bore the Elsinore name (The name was derived from the famous Elsinore Grand Prix). The thing that made this CR different from previous models was that big blue “R” on the side panel. The R stood for works “replica” and it signified that this was indeed a new breed of CR. Eventually, the R in the name would become a staple of Honda motocrossers and loose its significance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

While the front forks were at least useable, the same could not be said for the Honda’s terrible Showa rear shocks. The stock shocks offered no adjustment, save spring preload, and lacked the remote reservoirs that were all the rage at the time. The shocks were laid down quite radically to allow for their extreme travel without increasing the R’s already substantial 37” seat height. In terms of actual performance, the Showa shocks were pretty abysmal. They were very harsh, with too much compression and heavy rebound damping. In addition to being poorly valved, they came standard with springs that were far too stiff and completely at odds with the soft front forks. In breaking bumps the shocks would kick and hop, preventing smooth breaking. Over small bumps, the shocks deflected instead of tracking straight, and upset the handling of the machine. The stiff rear end only proved useful on massive jumps. Unfortunately, jumps that the shocks would take in stride, would bottom the forks, and chop that the forks would swallow easily, would send the shocks skyward. The real answer to fixing the Honda’s suspension was a set of Moto-X Fox Air Shox. The $300 dollar units transformed the performance of the CR and were used by everyone from local hot shoes to Factory riders. Setting them up properly was no easy feat, but they were worlds better than anything else available at the time.

|

| When Honda set out to build the ’78 CR250R, they were influenced heavily by the best European designs of the day. The frame shared more than a passing resemblance to a Husqvarna design, and the right-drive, left-kick was as Euro as it got in ’78. While the Husky-clone frame handled very well, the wimpy steel swingarm and gruesome rear shocks needed to be addressed to get the most out of the Red Rooster. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

|

| The Holly Grail of seventies suspension, The Moto-X Fox Air Shox was a suspension revolution in the seventies. Originally designed by Bob Fox (brother of Fox Racing founder Geoff Fox), the pneumatic shocks did away with springs altogether (much like modern air forks). The Air Shox offered far superior performance to the traditional shocks available at the time, and everyone from amateurs to Factory stars used these $300 shocks in the late seventies. Their only drawback (other than cost of course, $300 was a lot of money in 1978) was their tricky setup (I actually had a set of these babies for my ’78 Elsinore and I could not for the life of me figure them out. Eventually I gave up and just lived with the crappy stock shocks). |

In the handling department, the ’78 Elsinore was excellent if you got rid of the stock shocks. Although many people were intimidated by its skyscraper seat height, the bike did not feel overly tall or top-heavy. With the garbage rear shocks ejected, the Elsinore could carve the inside line and gobble up a rough forth gear straight with equal ease. The bike was an excellent jumper as well, as long as you could master its abrupt power delivery (see said loop-outs above). The frame on the R was genuine chromolly steel and a definite step above earlier efforts (The steel quality on early Japanese bikes were generally considered far inferior to the best from Europe). Unlike the YZ and RM-C2, the CR stuck with a steel rear swingarm. This proved to be a major oversight, as the stock unit proved to be prone to a great deal of flex and problems over time. Like the shocks, aftermarket alloy swingarms were a popular upgrade on the Red Rocket.

The stock Showa shocks offered an astounding 11-inches of travel, but only used half of it. They were badly oversprung and harshly damped. When combined with the overly soft front forks, the CR offered a miss-matched rodeo ride worthy of a Jeff Emig “Huck-a-Buck”. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Detailing on the ’78 Elsinore was excellent overall. The bike was incredibly durable (I personally tried to kill mine with K-Mart oil and a complete lack of maintenance and it took it all in stride). The brakes worked very well when dry, but typical of most drums, got very dicey when wet. The only real pain in the butt associated with the otherwise well thought out CR250R, was its nightmarish air filter maintenance (I have owned 50 bikes, and of all of them, this was by far the worst). The filter was stashed in a cramped little airbox and held in place by an assortment of tiny nuts and clamps that loved to get lost in the dirt. Once you got the stupid filter out and cleaned, it was a thirty-minute affair to get the dumb thing back together. Worst of all, the consequences for not cleaning the filter were pretty dire, because the chrome cylinder bore could not be repaired or re-bored. If you roached one, it was off to the Honda dealer for a new several hundred-dollar cylinder. Ouch!

Easily one of Honda’s most iconic designs, the ’78 CR250R Elsinore is every bit as striking today as it was in 1978. At $1498 it was a screaming deal and offered near works performance for the rider who could make use of it. Even today, the awesome ’78 Elsinore remains in many people’s minds, the quintessential Honda motocrosser. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The incredible ’78 CR250R Elsinore was a groundbreaking machine. I signaled Honda’s renewed commitment to motocross racing and offered real works bike performance for the masses. It was the first bike to approach a full foot of travel (still the amount used today) and had a motor capable of wining AMA Nationals right out of the crate. Even today, the ’78 Elsinore continues to be one of vintage racing’s most coveted rides. Every weekend, all over this great county, people continue to ride the Red Rooster to victory. It was a bike that captured the imagination of a generation of motocross enthusiasts, and continues to be a dream machine today.