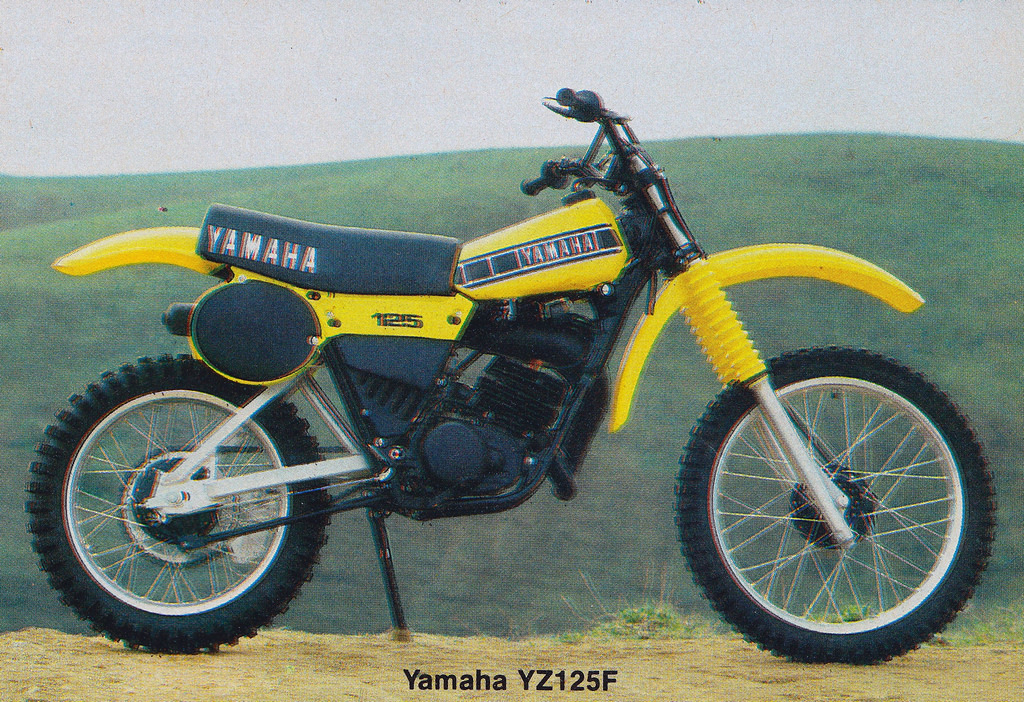

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the 1979 Yamaha YZ125F.

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the 1979 Yamaha YZ125F.

|

|

In the late 1970’s, Yamaha and Suzuki were the powerhouses of American Moto. Honda was still trying to regain the momentum they had with the first Elsinore and Kawasaki was little more than a curiosity. In 1979, Yamaha once again went back to the drawing board in an attempt to unseat their yellow rival as the top 125 in the land. |

In the late 1970’s, the 125 class was the hottest division in American motocross. The light, nimble and fun machines offered big bike performance, at a price a paperboy could afford. Starting in the fall of 1973, with the introduction of the first Honda CR125M Elsinore, the popularity of these entry-level machines skyrocketed. The Elsinore was the first in a new wave of high tech machines from Japan, which would come to dominate the class, and eventually the entire sport.

|

|

In 1972, Yamaha introduced their first machines designed specifically for motocross. The AT2-M (125), DT2-MX (250) and RT2-MX (360) were stripped of all the enduro froof and aimed at racers, rather than trail riders. |

While Honda was the first manufacturer to produce a truly race-ready and affordable 125, they were far from the first Japanese manufacturer to build a small-bore race bike. Yamaha had been one of the pioneers of Japanese motocross racing with their original AT1-M Enduro in 1969. The AT1-M was no serious race bike, but it made a good starting platform for a generation of enthusiasts looking to get into racing. With a little modification, the AT1 (125), DT1 (250) and RT1 (360) could be transformed into a decent entry level motocross mount. Yamaha offered a GYT (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) kit consisting of a high compression cylinder head, a ported cylinder, piston, expansion chamber, bigger carb and a magneto to turn the little enduros into a racer. The kit did nothing for the bike’s street oriented suspension and chassis, but did perk up its motor performance substantially.

|

|

For ’79, Yamaha went with refinements, rather than reinvention for their 123cc mill. A new cylinder featured bigger transfers and a more streamlined exhaust manifold. A redesigned head bumped up the compression and a new ignition heated up the spark. In the transmission, third and fourth gears were beefed up and the shift mechanism was refined for a more solid engagement. |

With the arrival of the 1972 model line, Yamaha finally did something about this deficiency by introducing its first “real” motocross bikes –the MX line. The new AT2-M (125), DT2-MX (250) and RT2-MX (360) were a significant upgrade from the enduro models and featured plastic fenders, more powerful reed-valve motors (a first for Yamaha) and slightly better suspension. While the MX models got rid of the enduro’s street running gear, they were still 15-20 pounds heavier than their European counterparts and better suited to desert fun than hard-core motocross.

|

|

Deep field: 1979 would see by far the most competitive 125 class of the decade. All the bikes were new or greatly changed and any one could win with the right pilot aboard. Even so, there really was only one star in this stacked field. |

In 1974, Yamaha would get serious about motocross with the introduction of their YZ line. The all-new YZ125-A featured a high tech motor and went head-to-head with Honda’s new 125 CR125M Elsinore. This first generation YZ, while quite an improvement over its more sedate (and less costly) MX125 cousin, was not quite up to unseating the mighty CR125M. The Honda won on the track and in the showrooms, outselling the more serious YZ three to one.

|

|

Y-Zed: Two years after the launch of the MX line, Yamaha would jump into the deep end with their YZ line of production race bikes. Lighter, faster and far more serious (and expensive) than their MX siblings, the YZ125 and YZ250 were aimed squarely at fast intermediates and pros. |

For Honda, its reign at the top of the class would be extremely short (if you can pardon the pun) lived. With the introduction of the 1975 ½ YZ125-C and its revolutionary long-travel “monoshock” rear suspension, the 125-class power structure would be flipped on its end. The short-legged suspension of the Honda would prove no match for the monoshock YZ and push the sales leader to third in a newly crowded field of race-ready 125’s.

|

|

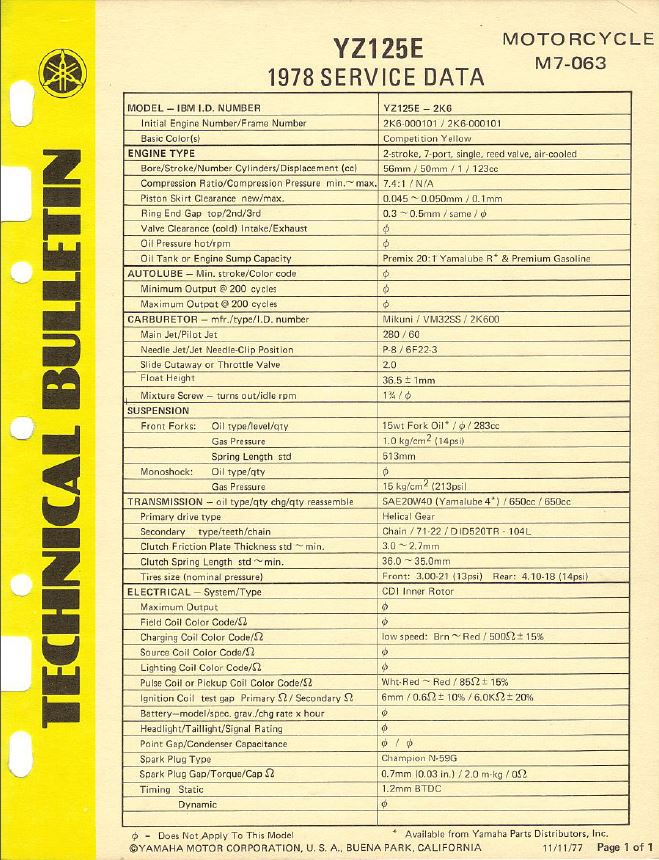

Wrench Report: One cool perk to riding YZ’s in the seventies and eighties, were these technical bulletins put out by Yamaha, known as “Wrench Reports”. The Wrench Reports took tips learned by the race team and made them available to anyone looking to upgrade the performance of their YZ. |

Taking second in 1975 would be a newly rejuvenated Suzuki. After years of poor offerings with their TM line, Hamamatsu came roaring back in ’75 with their all-new works-inspired RM125. The RM125 featured long travel suspension front and rear and combine it with an easy-to-ride motor. The new RM’s laid down dual shocks actually outperformed the high tech monoshock of the Yamaha, but its mellow five-speed mill held it back from claiming the top step in ’75.

|

|

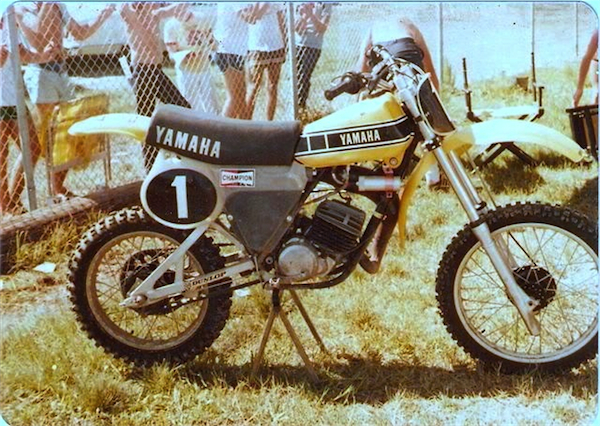

The Golden Boy: While the stock YZ125’s performance consistently lagged behind the Suzuki’s of the time, the OW works bikes did not seem to suffer the same deficiencies. Bob Hannah and Broc Glover would capture four straight 125 National Motocross titles for Yamaha from 1976 to 1979. |

The ’76 season would see the third lead swap in three years, with the ascension of the all-new RM125-A to the 125 top spot. For ’76, Suzuki threw out virtually everything from their very good ’75 model and came out with a machine that would dominate the class for the remainder of the decade (and well into the next one). The ’76 RM offered class-leading suspension, mated to a strong and easy-to-ride motor. The high-tech YZ125-X offered a slightly faster motor and trick air-forks, but cost significantly more than the others, and required a skilled hand to maximize its potential.

|

|

Brraapp: After the listless ’78 model, the punchy power of the ’79 YZ was a welcome change. |

|

|

Power on the ’79 YZ125F was soft off the line, barky in the middle and mediocre on top. It did its best work in the midrange and offered a competitive (all be it short) spread of ponies. By far its biggest deficiency was its stubborn transmission, which refused to be upshifted under power. |

Once again in third, we had Honda. The little CR125 continued to enjoy strong sales in the marketplace, largely due to excellent aftermarket support and the exploits of Marty Smith, but its performance lagged behind the YZ and RM. With major aftermarket massaging it could be made to be a competitive mount, but box stock, it was outclassed by the other two.

|

|

In 1979, the RM125 had the field covered. It was the fastest bike, with the broadest power and the best suspension. The only category it did not win was cornering, where the short-legged YZ125 had an advantage. |

In last, we had Kawasaki, which had never been a major player in the 125 marketplace. Although an early small-bore pioneer with their 1970 100cc G31M Centurion (often referred to by the name of its 250cc brother, “Green Streak”), the green machines had never made it past bit player status in the 125 class. The KX offered a user-friendly (slow) motor, but had suspension performance that would have been considered poor in 1971. In 1976, if you did not ride yellow, you were in for a long season.

|

|

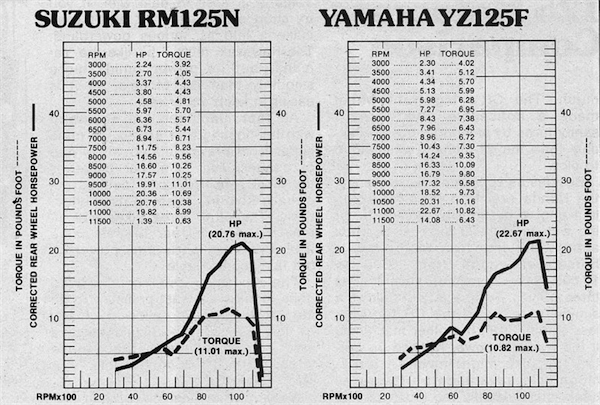

Power picture: On paper, the 1979 YZ125F offered the most peak power of any production 125, but that did not tell the true story. One look at its torque curve shows why it lost out to the RM. After its solid punch in the midrange, the YZ went flat for 2000 rpm, before picking back up near redline. This flat spot made the YZ feel peaky compared to the broad power of the RM125. |

In ‘77 and ‘78, this titanic battle once again played out between the two top guns of 125 class racing. After the drubbings of ’75 and ’76, Kawasaki decided to sit out the ’77 season altogether and focus its efforts on their upcoming ’78 KX125 A-4. For ’77, Honda once again trotted out a tarted up ’74 CR125M and once again got drubbed by the competition. The CR offered slightly more travel than before, but its suspension action was poor and its pipey reed-valve-less motor was too hard to ride. In the final standings, Suzuki once again topped the 125 rankings with its excellent suspension, solid chassis and flexible motor.

|

|

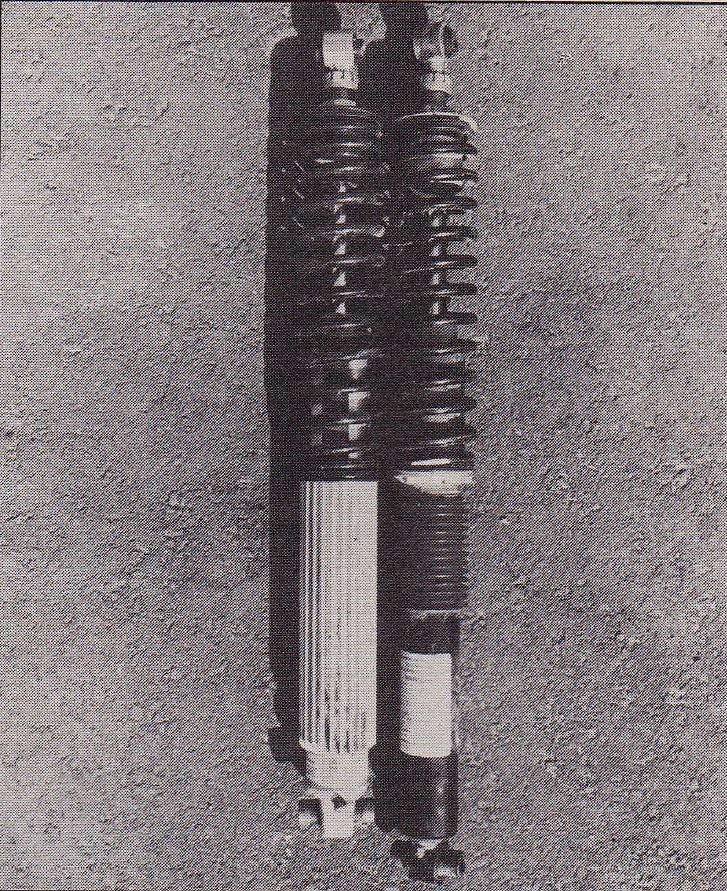

A new frame for ‘79 necessitated a new shock as well. The YZ125F shock was actually two inches shorter than the year before, but offered more travel due to a new swingarm. The new shock was also lighter, due to a switch to alloy construction. |

In 1978, it would be Honda’s turn to take a sabbatical in order to regroup for the ’79 season. For Kawasaki, the arrival of their new limited production KX125 A-4 would signal a renewed commitment to motocross for the brand. The A-4 was fast, light and incredibly hard to find. The bike was virtually impossible for the average rider to buy and doled out to local pros by Kawasaki in order to raise brand awareness. As with the previous three years, the final battle of ’78 would come down to Yamaha and Suzuki. For ’78, the YZ offered a new chrome-moly steel chassis and boxed alloy swingarm, but actually took a step backwards in performance. The ’78 YZ125-E turned out to be slower than the ’77 F-model and unloved by most testers. When you added in its quickly aging suspension performance to its peaky motor, thing started to look bleak for the Y-Zed. Once again, the title of best 125 went to the Suzuki RM125 in a rout.

|

|

In the years between ’76 and ’80, Yamaha actually switched back and forth between liquid-cooling and air cooling on their works 125’s. Amazingly, the jury was still out on whether the added weight and complexity was really worth the performance gains it offered. |

Nineteen seventy-nine would prove to be a big year for 125 fans, as it would see the first Big-Four showdown in the class since 1976. Honda was set to debut their all-new CR125 “R” works replica, while Kawasaki had a majorly revised KX125 A-5 on tap. Suzuki, for their part, had more travel, a revised motor and all-new bodywork in the works for the class champ RM. With the YZ, Yamaha dialed up the third all-new frame in as many years and a slew of motor changes aimed and finding the ‘78’s lost ponies. With four virtually new machines poised to do battle, 1979 looked to be a knockdown, drag-out battle for 125cc supremacy.

|

|

While the YZ’s meager nine inches of suspension travel hurt it in the rough stuff, its low-slung stance gave it a sure-footed feel in the twisties. Steve Bauer demonstrates. |

While visually the Yamaha YZ125F did not appear be a much different motorcycle than the E-model it replaced, it was actually a whole new machine. Outwardly, the only differentiating visual queue between the two machines was the addition of a new more rearward mounted FIM mandated sideplate on the ‘79. Otherwise, the E and F looked virtually identical. When you dug a little deeper, however, you could see Yamaha put their money into true R&D, not just BNG.

|

|

The YZ125F’s 36mm Kayaba forks were both too small in diameter and too short in travel. Compared to the class leading Suzuki, they were two millimeters smaller and over in inch shorter. In addition to their size deficiencies, overly soft springs and insufficient damping control held them back from beating anyone but Honda in ’79. |

After several years of being drubbed by the awesome RM125, Yamaha was out to gain back the lead in 1979. In order to steal back the 125cc crown, Yamaha spec’d an all-new frame for the ’79 YZ. The new chassis featured a ½ degree steeper head angle and 5mm less trail than the ’78 for tighter turning and better response. The frame’s backbone was redesigned; relocating the monoshock two-and-a-half inches rearward and repositioning the swingarm pivot a half-inch closer to the countershaft for improved handling. The new frame was also lighter, with a smaller diameter monocoque tube for the shock and thinner diameter tubes in the frame rails. A new swingarm was employed that featured a rolled-edge construction and additional bracing to fight flex (and hopefully avoid the cracking seen on the ’78 model). In order to accommodate the new frame, Yamaha spec’s an all-new shock for the YZ that was a full two inches shorter than the E-model’s. Although shorter overall, the new monoshock offered slightly more travel than the year before. Rounding out the chassis changes were a half-inch more travel for the forks and a switch to a full-floating mount for the rear brake.

|

|

In an effort to aid cooling, the ‘79’s new shock was heavily finned at the base. Even so, it suffered from severe heat fading after 15 minutes of hard use. |

While there had been some criticism of the ’78 YZ’s chassis, the majority of the complaining had centered on its power plant. The E-model Y-Zed had offered a top-end focused power spread that made good numbers, but put them out of reach of most mortals. Below the strong top-end, there was little usable power and the YZ was a handful for anyone not named Glover. For ’79, Yamaha went looking for the missing grunt with a series of careful refinements to the E-model’s motor. For the F-model, Yamaha redesigned the ports with larger transfers and a streamlined exhaust port for better flow. A new head raised the compression and a new pipe helped move out the spend fuel after the revised ignition set it ablaze. In the transmission, Yamaha decreased the angle of the shift dogs from 3 degrees to 1.5 and additional material was added to third and fourth gear. Finally, a new set of bearings were added to both sides of the shift drum to help smooth the Yammie’s cantankerous gearbox.

|

|

Ratty: In the seventies, stock silencers were made of heavy gauge steel and completely unserviceable. |

On the track, the revised ‘79 mill was better for most riders than the pro-oriented ‘78. It was no Open bike off the line, but it had enough power to pull without bogging. In the mid-range, the 123cc mill perked up with a nice hit, before falling off the pipe as the revs climbed. On paper, the YZ put out the most ponies of any Japanese 125 in 1979. Its 22.67 horsepower peak looked impressive, but one look at the power curve of the RM and YZ side-by-side told the true story. Where the YZ hit hard and then hiccupped, the RM just kept pulling over a broad and strong spread of power. Making matters worse was the YZ’s recalcitrant transmission, which in spite of Yamaha’s attempts, still refused to be shifted under power. In the final standings, it was once again the brawny RM in the lead, followed by the upstart and extremely green KX, with the dyno star Yamaha and boggy CR bringing up the caboose.

|

|

Mono: Just as in the front, the Monocross rear of the YZ was at a travel disadvantage to the competition. At 9.1 inches, it gave up nearly 2 full inches to the Honda and Suzuki. In addition to its stubby nature, the shock’s overly stiff damping, propensity for kicking and notorious fade problems did it no favors. |

Unfortunately for YZ fans, the story did not get much better in the suspension department. In 1975, the YZ’s monoshock had been a suspension revelation, but by 1979, it had fallen behind the competition. It offered a narrower profile than the dual-shock competition, but its travel advantage had been negated by the radically cantered LTR (Long Travel Rear) shocks offer by the competition. For ’79, that discrepancy looked to be getting even worse with Honda’s new RC replica CR125R and Suzuki’s omnipotent RM both boasting a full 11 inches front and rear. Even with the changes to the frame and suspension for ’79, the YZ offer only 9.8 inches up front and an embarrassing 9.1 inches in the rear. This put the YZ at a significant disadvantage both in the magazines and on the track.

|

|

Detailing was a bit of a mixed bag on the ’79 YZ125F. On the good side, plastic thickness was doubled for on the YZ-F, fighting flex and breakage. The new levers that graced the ‘79 had small detents molded in for each finger that were loved by the testers. Seat comfort was also high and most testers picked the YZ as having the best butt comfort of ’79. In the not great category, were the not-long-for-this world decals, cheesy rubber band mounting for the front numberplate and top chain roller, which snapped of after the first hard landing. |

Exacerbating this suspension deficiency was the design of the Monocross suspension itself, which buried the shock deep in the frame under the seat and tank. This meant the shock received very little in the way of air circulation and made these shocks very fade prone. On the big YZ’s, Yamaha fought this problem by hanging a massive remote reservoir off the front of the frame where it could receive the most cooling air. With the YZ125, however, pilots had to make do without the remote reservoir. This meant both less oil capacity and less cooling. Not a recipe for excellent performance.

|

|

Brake it to me: The braking on the ’79 YZ was as mismatched as its suspension. Front action was excellent, with good power and feel. Out back, however, the new full-floating binder was a grabby, chattery, light switch. |

With the YZ’s rear end performance, it started out mediocre and quickly degraded to poor. When fresh, the mono was harsh on compression and slow on rebound. It would deflect on hard hits and pack down in the whoops. Then it would get hot and slowly turn into a pogo stick as the damping went away. There was a rudimentary damping adjustment available via a screw under the tank, but none of the available setting made an appreciable difference in performance. Smart riders opted for an aftermarket unit that added a remote reservoir like its big brothers. In the ’79 rear suspension standings, it was Suzuki out front by a country mile, followed by the pro oriented Kawasaki and flawed Yamaha. In last, also by a country mile, was the harshly suspended Honda CR125R.

|

|

The layout of the ’79 YZ was the slimiest in the class, due to its monoshock suspension. Tank and seat comfort were excellent, and the bikes short stature made it and excellent mount for younger and shorter riders. |

Up front, the YZ used a set of 36mm Kayaba air/oil forks that offered 9.8 inches of travel. This was half an inch more than the year before, but far less than the Honda and Suzuki. Also hindering the YZ, were its 36mm legs, which were much less precise than the beefy 38mm legs found on the RM. Performance was much softer than the overly stiff rear and gave the bike an unbalanced feel on the track. Adding air to the forks could alleviate some of that soft feel, but that came at a price of plushness. Overall, it was once again the Suzuki in a rout, followed by the KX, YZ and deeply confused Elsinore in last.

|

|

Hurricane sighting: Buckwheat himself, made a rare 125 appearance in ’79, riding the 125-support class at the USGP. |

In the handling category, the YZ faired much better. That short suspension that hindered it in rough, helped may the Zed very good in the corners. It felt much less tippy than the tall Honda and Suzuki and offered a sure and planted feel in the turns. Only the racy KX125 A-5 was better. Stability was decent overall, with little headshake, but the bike’s subpar suspension made the machine unpredictable at times in the rough. Big whoops were best approached with caution, as the YZ was not immune to a sudden “Yama-hop” at speed.

|

|

While the YZ125 is revered as an icon of seventies motocross, that fame is more due to the men who rode it, than the bike itself. In ’79, Yamaha built a virtually all-new YZ125, which was still a step or two behind the competition. It needed more power, longer suspension and better damping to compete with the class top dog, RM125. For Yamaha, it would take another seventeen years for them to once again claim the top spot in the 125 class. |

In the late seventies, the YZ125 was always the bridesmaid of the class. Overall, it was a solid, if flawed, machine that introduced thousands of teenagers to the joys of motocross. At $1257, it was the cheapest of the ’79 125’s and decent choice if you absolutely refused to ride a Suzuki. It was easier to ride than the Kawasaki (and 400% easier to get parts and support for) and better performing than the Honda, but just not up to toppling the Hamamatsu Hauler as the best 125 of 1979.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier