For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1991 Yamaha YZ125.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the 1991 Yamaha YZ125.

|

|

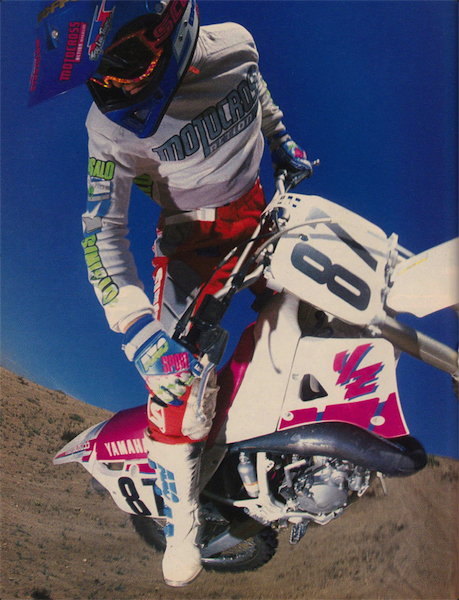

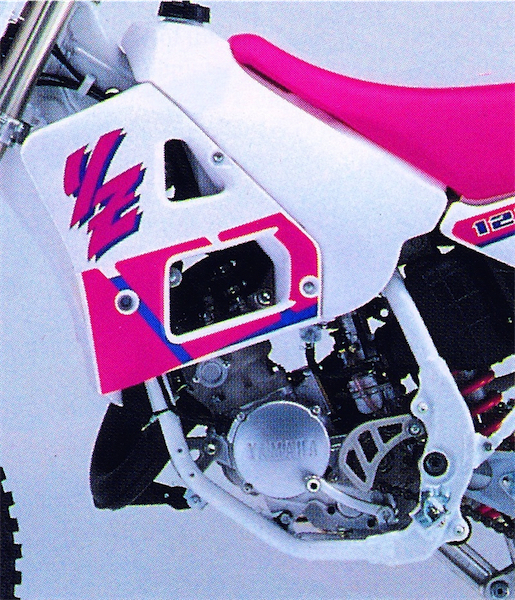

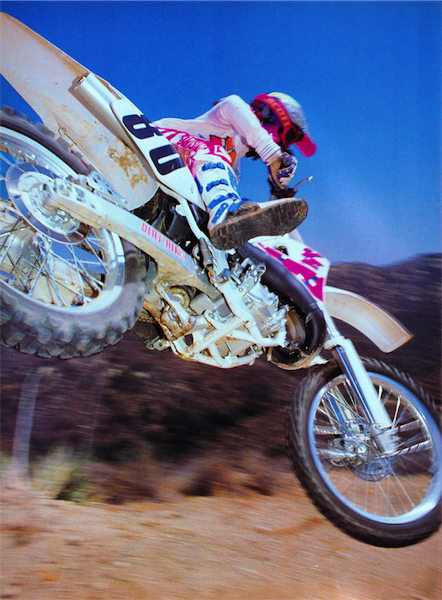

In 1991, Yamaha introduced an all-new YZ they hoped would finally claim their long-sought 125 class crown. The new YZ was boldly styled, brightly colored, but lacking in the one area most vital to 125 class competition. |

In 1991, Yamaha was one of the hottest brands in motocross. After a rough spell in the early 80’s, the tuning fork brand came roaring back in the latter part of the decade with sexy designs and solid performance. Although the glory days of Glover and Hannah were in the past, a bright new future was on the horizon with the arrival of the most highly-touted amateur the sport had ever seen, Damon Bradshaw. Bradshaw turned pro full time in 1989 and immediately served notice that all that hype had been fully justified. The rookie took the sport by storm with blazing speed and a flashy style that electrified fans from coast to coast. With new and much improved bikes in the stable, and the hottest prospect in the sport under their tent, the nineties looked to be shaping up for return to glory for Yamaha.

|

|

With the benefit of a new chassis and greatly upgraded suspension, the ‘91 YZ125 turned out to be one of the best handling bikes of ’91. |

|

|

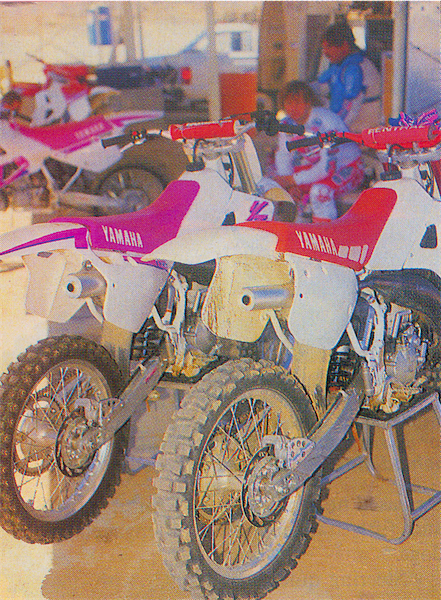

Swoopy new bodywork and a change of color from red to magenta gave the YZ a fresh new look for ’91. (1991 YZ125 left, 1990 YZ125 right) |

For 1991, Yamaha looked to capitalize on their momentum with an all-new YZ125. In 1990, The YZ had been a solid performer, but no stand-out in any one category. Its power was punchy, but short on breadth and its chassis was stable, but less accurate than the competition. It was competitive and a far cry from the dark days of the early 80’s, but no superstar.

|

|

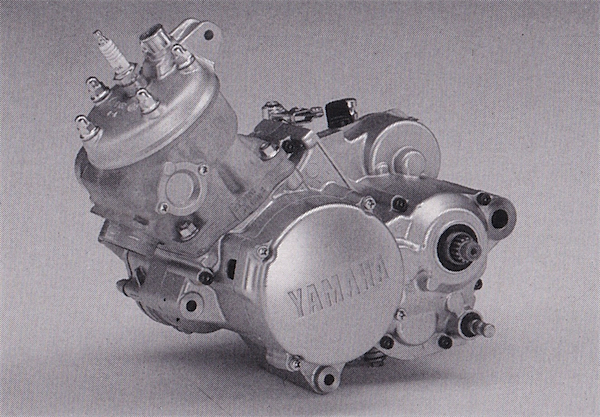

Originally introduced in 1986, the YZ’s 124.8cc case-reed mill had always produced excellent midrange, but little else. For ’91, Yamaha spec’d a new cylinder, head, exhaust pipe, ignition, reed-valve and YPVS valve in an effort to pull more top-end power out of their one-dimensional mill. |

For 1991, Yamaha went whole-hog on the new YZ. An all-new frame was spec’d and bolted to new suspension front and rear. New bodywork was designed and painted a bright new coat of magenta unlike anything previously seen from conservative Yamaha. Perhaps most important (and certainly most concerning to longtime Yamaha owners), was the YZ’s new power plant, which received a major overhaul for 1991. In the 125 class, power was everything, and if the YZ was going to finally win back the class title, the new motor had to be good.

|

|

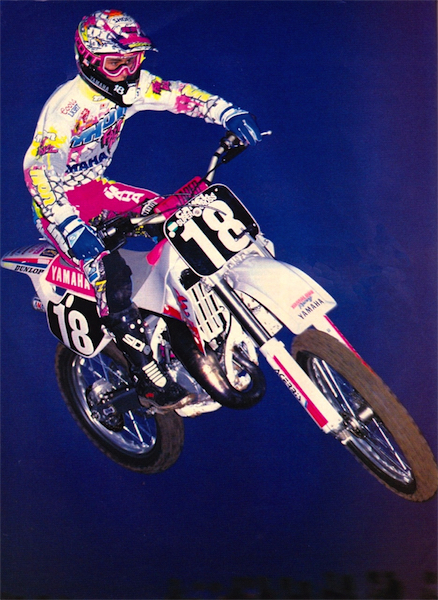

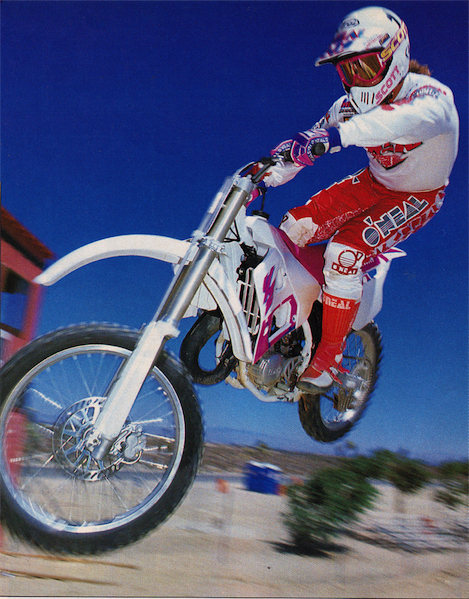

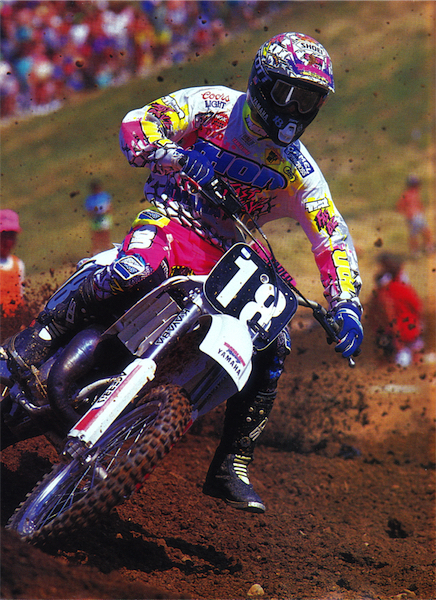

In 1991, Jeff Emig made the jump from Factory Kawasaki over to Yamaha. Jeff would have an excellent year on his new YZ, carding four victories and finishing second overall to Peak Honda’s Jeremy McGrath in the final 125 West Coast SX standings. |

|

|

DOA: In an sad bit of irony for Yamaha, its engineers’ quest for more top-end power actually ended up killing the old motor’s one virtue. Without its hard-hitting midrange, ’91 YZ pilots were left with an anemic, uninspiring and pathetically slow stable of ponies. On the dyno, the new YZ looked impressive, but on the track, she was in a world of hurt. If the track was fast and hard, the YZ had a prayer, but if the dirt was deep and tacky, the poor Y-Zed became cannon fodder for the red, yellow and green competition. |

For 1991, Yamaha looked at the punchy, midrange motors they had been producing since 1986, and tried to broaden that power out across the rev band. It was no secret that every manufacturer (and virtually every rider) craved the endless rev and top-end pull of the Honda CR125R, and Yamaha wanted some of those accolades for ’91. In pursuit of that top-end power, Yamaha revamped the port timing, reshaped the intake and exhaust ports, spec’d a new YVPS valve, bolted on a new pipe and installed a new ignition in their 124.8cc case-reed mill. Rounding out the motor changes was a new “ratchet-type” shifter that aimed to finally fix the YZ’s shifting woes.

|

|

With the stock ‘91 YZ literally too slow to outrun a 1984 KX125, people were quick to try and find some reason for the new bike’s disappointing performance. Some of the bike’s lost low-end and poor response could be attributed to mixed up factory jetting and a defective reed-valve. By leaning out the pilot circuit and adding a second set of reeds cut in half to stiffen the weak stock ones (preventing reed flutter), some of the of the lost response could be reclaimed. Even with these mods and the help of an aftermarket exhaust, the YZ still remained the slowest bike in the field by a gapingly wide margin. |

|

|

Lost in translation: In the summer of 1990, Dirt Bike Magazine was invited to try out the pre-production ’91 YZ’s and came away raving about how impressive the new bikes were. Inexplicably, however, once the production YZ125 was released, that rocket-fast pre-pro motor was nowhere to be seen. Somewhere between development and production, the power went missing and test riders like Gentleman Jim Holley were left scratching their heads. |

|

|

While Yamaha superstar Damon Bradshaw was prominently displayed in ads for the all-new YZ125, his early departure to the 250 class meant he would spend the season on the much more competitive YZ250. |

|

|

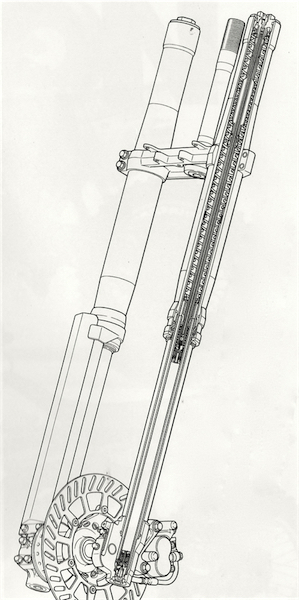

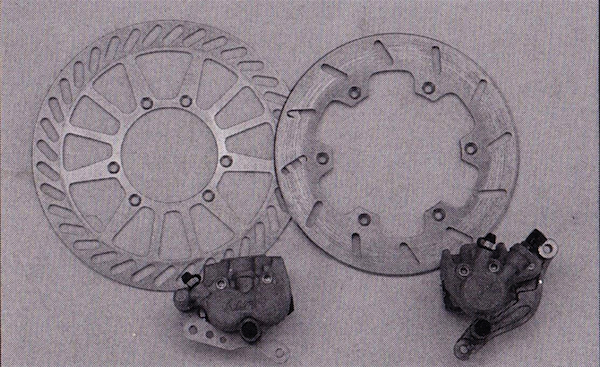

A new KYB fork for 1991 upped the tube size from 41mm to a 43mm for increased rigidity. The “works-style” cartridge unit offered 20 settings for compression and rebound, as well as a screw-type pre-load adjuster. One interesting feature was Yamaha’s movement of both adjusters to the top of the fork for easier tuning and less time spent lying in the dirt. |

|

|

While the stock YZ left more than a little to be desired in the motor department, the works version suffered no such deficiency. Jeff Emig’s Factory YZ125 was reported to be on the fastest 125’s in the entire country, and a potent holeshot machine indoors and out. |

So was the ’91 YZ125 mill the high-rpm powerhouse so longed for by Yamaha aficionados? In a word, no. In fact, the ’91 mill turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. In their effort to elongate the YZ’s midrange only powerband, the engineers killed its one defining trait. The new pink Yammer no longer barked to attention and exploded out of turns. Now it groaned under a load and wheezed down the straights. Low-end was never a YZ virtue, but the new motor was a bottomless pit of bog out of the hole. The previously meaty midrange was nonexistent and followed by a pathetic pull on top. This was by far the slowest YZ125 motor since the dark days of 1985 and virtually worthless as a racing motor. Adding to the YZ pilot’s woes was a notchy and recalcitrant transmission that still refused to be shifted under a load. When you considered the fact that the anemic YZ was likely to be kept at full throttle at all times, you could see the potential problem this could cause.

|

|

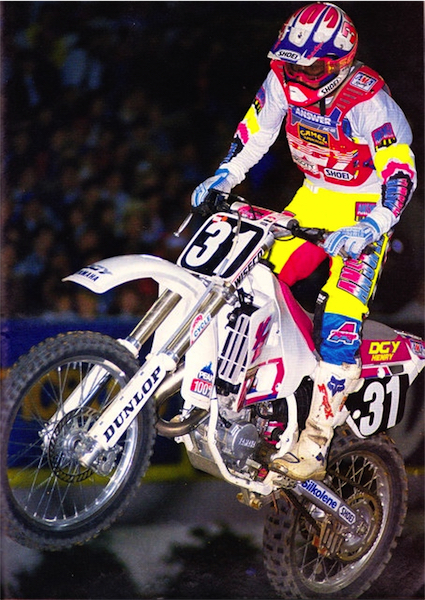

In the early ‘90’s the satellite team movement really started to take off in motocross. After years of full Factory or basically nothing, a secondary tier of support teams sprung up to give up-and-coming riders a new place to land on their way to the big truck (or a place to land after an unceremonious exit from it). Teams like Peak Pro Circuit Honda, DGY Yamaha (pictured here with Doug Henry at the controls of his ‘91 DGY YZ125), NCY Yamaha and Honda of Troy would quickly change people’s minds about the legitimacy of privateer teams. |

In an attempt to find the missing ponies, Yamaha was quick to make some Wrench Report recommendations. Apparently, some of the stock bike’s midrange malady was due to reed flutter and the hot set-up was add a second set of reeds cut in half over the stock peddles to stiffen them up. They also recommended leaning out the pilot to crispin up the boggy low-end response. The last Band-Aid fix was to swap out the new two-stage Power-Valve governor for the single-stage unit used on the ’90 YZ. If you made all these mods, the YZ perked up in the low-end and midrange, but still lacked any sort of top-end pull. If the track was hard-pack and smooth, the YZ could be ridden competitively by leaving it pinned and rowing the notchy gearbox at a lighting pace. If, however, the track was loamy, sandy or hilly, you were going to be eaten up by the red, yellow and green competition.

|

|

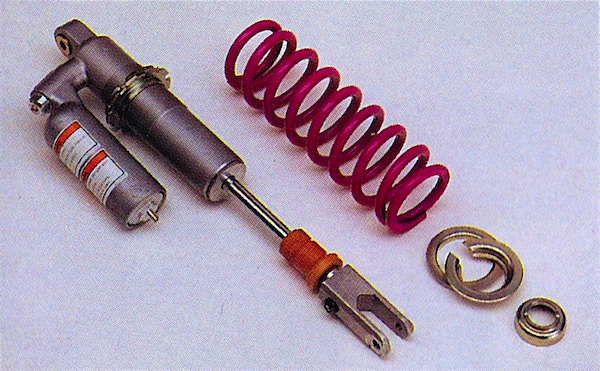

A new Kayaba shock for 1991 added a new magenta spring and an additional .5 inches of stroke over the ’90 model. The unit offered 22 adjustable settings for compression and rebound and a total of 12.4 inches of rear wheel travel. |

|

|

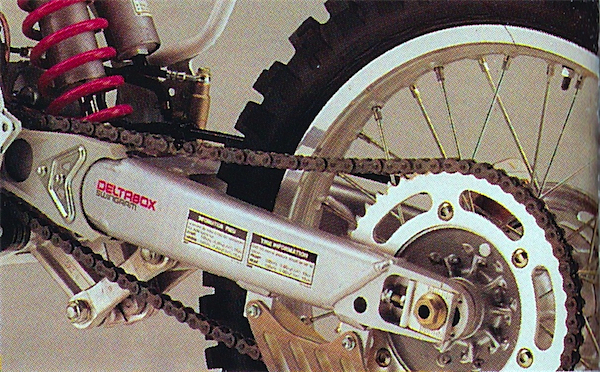

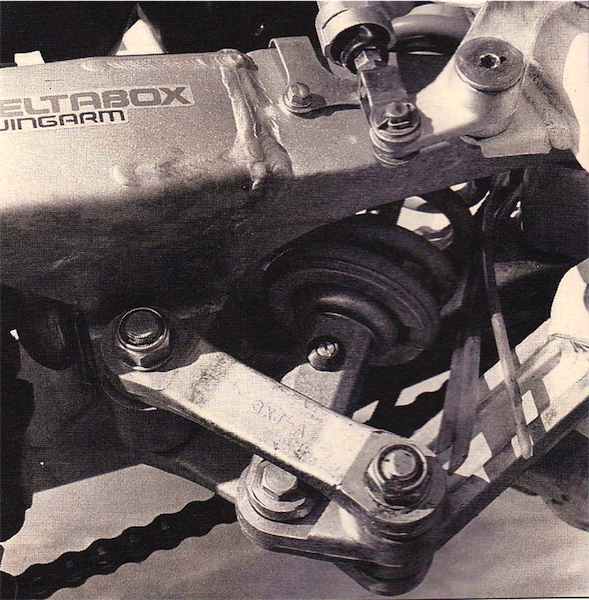

Another new feature for 1991 was a redesigned swingarm and linkage for the Monocross rear suspension. The new swingarm used a “Deltabox” design sourced from Yamaha’s road race department. Deltabox was Yamaha’s name for the large, hollow, extruded aluminum beams used as frame members on their FZ-R road race machines and was prominently displayed in their advertising at the time. Because of the more advanced construction, the new swingarm was both lighter and stronger than the outgoing design. |

While the motor on the ’91 YZ125 turned out to be a massive disappointment, the rest of the bike was a solid package. The new frame was stiffer and combined with a new “Deltabox” rear swingarm and beefy 43mm inverted forks to give the new YZ a very solid and flex-free feel. Turning was greatly improved over the slightly inaccurate ’90 model, while maintaining the excellent stability Yamaha was known for. It was not as sharp as the Ginsu-like Honda and Suzuki, but more agile than the big-feeling Kawasaki. If the track was fast and rough, there was no better mount than the YZ, as it could be bombed through terrain that would have a Honda or Suzuki pilot chanting Hail Marys. This of course was a good thing, because if you ever actually slowed down on the YZ, you were in for a world of hurt trying to get back up to speed.

|

|

The new handholds molded into the plastic were a welcome addition for ‘91, but the new bodywork’s odd budge on the silencer side harkened back to the days of dual shocks and annoyed some riders. |

In the suspension department, Yamaha once again outperformed their pathetic motor by a wide margin. The new “works-type” 43mm inverted cartridge forks were 2mm larger than the year before and featured both compression and rebound damping adjustability. Performance was very good, with decently plush action and well sorted spring rates. Overall feel was not as plush as the Kawasaki’s excellent silverware, but it was in the ballpark for most riders.

|

|

The new 43mm KYB’s on the YZ were well sorted and fairly plush in action. Stock spring rates were fine for all but pros and most riders could find acceptable settings with the adjustments available. |

|

|

Shortly after the ’91 YZ’s introduction, MXA dubbed the new Monocross linkage system the “cow-catcher” for its low-hanging nature and propensity to get hung up on whoops and peaked jumps. |

Out back, a new “Deltabox” swingarm was mated to a redesigned Monocross linkage and new Kayaba rear shock. The new swingarm was reportedly both lighter and more rigid than the outgoing “box-section” design and devised from Yamaha’s road race technology. The new linkage was designed to provide a more progressive action and improved feel on Supercross style obstacles. Like the forks, the shock did an admirable job of taming the track. Action was plush, well sorted and a significant improvement over the year before. Bottoming control was very good and most riders found the bike easy to dial in with compression and rebound adjustments. Again, it was not quite as plush as the excellent Kawasaki, but it was certainly raceable in stock condition.

|

|

What handles great, looks good and is slower than a Toro lawn tractor? |

Detail-wise, the new magenta YZ125 was at the upper end of the ’91 pack. Reliability was far better than the KX and RM, but not quite as stone-axe reliable as the Honda CR. Braking was much improved for ’91, with better feel and none of the squeaking, grabbing and chirping that annoyed riders in ’90. Cool details like the integrated bike handholds made lifting the YZ a breeze and the swoopy new plastic freshened the bike’s appearance. While certainly a bold departure, most people actually liked the new magenta look and preferred it to the old bike’s rather stale appearance (and hideous red anodized forks). In the ’91 appearance sweepstakes, the pink YZ actually looked conservative compared to the tiger-striped Honda and Rorschach-testSuzuki.Ironically, the most sedate looking bike of ’91 turned out to be the Kawasaki, which only a year previous had looked like a Buck Rogers space bike. The ‘90s were a strange time indeed…

|

|

New “works-style” brakes front and rear offered better power and feel, with less squealing and better pad life. |

|

|

After a very successful Supercross season, Emig’s first outdoor season on the YZ125 turned out to be a slight disappointment. Even though the #18 was held without a victory, his consistent finishes would be enough to earn him third overall by the end of the series. |

|

|

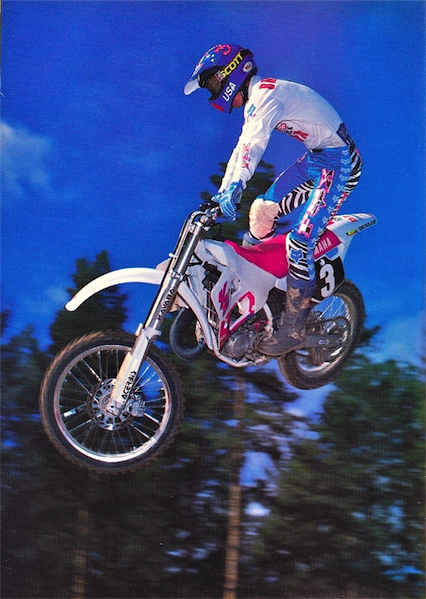

Damon Bradshaw was a controversial pic to be on the 1990 Motocross des Nations team over 125 National champs Mike Kiedrowski or Guy Cooper. By this point, Bradshaw was a 250 rider and many thought stepping him back down to the small bike was a mistake. Adding insult to injury, Damon’s 1991 production-based YZ125 was noticeably underpowered again the full works 125’s of the competition. As a result, the Beast struggled in the Swedish sand, before knocking himself out (literally) of competition in a nasty midair collision with Ireland’s Alan Morrison. Thankfully, a change to the MXdN rules for 1990 allowed the USA to drop Damon’s 2nd Moto DNF and preserve a narrow victory over Team Belgium. |

|

|

After a solid run of YZ125’s, the 1991 Y-Zed turned out to be a colossal disappointment for Yamaha. The little YZ was well suspended and excellent handling, but to slow to be competitive in any class above the novice level. With the right tuner and a stack of cash, the YZ could be turned into a winner, but without major help, the Yammer was doomed to eat roost for thirty plus two every weekend. |

In 1991, Yamaha shot for the moon with their 125, but ended up burning up on re-entry. The new-look YZ featured a very old-look powerband that harkened back to the dark days of the early eighties. It was a bike improved immensely in every category, save one. Unfortunately, that one deficit was a non-starter for most 125 hot-shoes. Without the ponies to run up front, the YZ was doomed to once again be the runt of the 125 class. With major motor work, the little Yammer could fly, but in stock condition, it was a bird with a bum wing.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier