For this week’s selection from Greg Primm’ Classic Steel we take a look at Suzuki’s first production motocross bike, the 1967 TM250.

By Tony Blazier

|

| The ’67 TM250 was a production replica of Suzuki’s RH67 “works” race bike. Both the works bike and the production version were seriously flawed motorcycles. Suzuki only produced 200 of these ultra-rare machines. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

The 1960s were a time of great change in the motocross world. At the start of the decade, the sport had been dominated by big British four-stroke singles. In the mid-sixties however things started to change as smaller, lightweight two-strokes from CZ and Husqvarna displaced the heavy four-bangers. The one thing that did not change was the fact that motocross in the sixties was still a primarily European sport. The best riders came from Europe, as did the best bikes. Little did they know, there was a sleeping giant awakening in the Far East.

|

| The TM250’s motor used a very unique design. The single cylinder two-stroke used twin exhaust ports feeding dual pipes. The clutch on the TM was actually mounted directly to the crankshaft as you can see in this picture. Because many bikes at the time had the shifter and brake on opposite sides of what is common now Suzuki sold the TM with a full length splined selector shaft exiting on both sides of the motor. You could mount the shifter on either side and with the mirror imaged rear-brake controls easily swap the rear brake from side to side as well. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

The Japanese in the sixties had virtually no presence in the off-road racing market. They had chosen to focus their racing interest on road racing, where they enjoyed a great deal of success. The initial impetus to go motocross racing came from Japanese enthusiasts, who were racing Suzukis in motocross, running street bikes with homemade modifications. In 1964, Suzuki decided to look into the possibility of entering the growing motocross market with a purpose-built off-road racer. Suzuki built two bikes for their riders to test, a road race inspired 250cc twin and a more off-road oriented two-stroke single. The truth of the matter was neither machine was very good. In 1965, the single cylinder version would be the basis for Suzuki’s first works motocross racer, the RH65. The RH65 was hopelessly outclassed in ’65 and had trouble even finishing a race. The twin T20 was even worse and virtually unrideable off-road. The Japanese were learning as they went along at this point and it was clear their road-race trained engineers had a lot to learn about off-road racing. The road race powerbands the bikes had were all top-end and incredibly hard to ride. The chassis on both machines were far too heavy and handled poorly. In short, the bikes were a disaster, but Suzuki vowed to come back with a much-improved machine for 1966.

|

| The stock TM front forks were supposedly based on the well-respected Ceriani front forks used on many European racers. In truth, they looked to have been pilfered off one of Suzuki’s street machines. The performance was predictably terrible. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

For 1966 the ill-handling T20 twin-cylinder bike was gone altogether, with Suzuki deciding to put all of its resources into an all-new single-cylinder purpose-built motocrosser. The RH66 was Suzuki’s first real dirt racer and the genesis of the company’s motocross lineage. The RH66 was much better than the road race inspired RH65 and T20 had been, but it still lagged badly behind the best bikes from Europe at the time. The RH66 never enjoyed any success on the track and was relegated to the obscure role of a development model. For 1967, Suzuki once again went back to the drawing board for an all-new works racer.

|

| The twin pipe design was a throwback to Suzuki’s road race heritage. The upswept design made for excellent ground clearance, but the dual pipes made the bike very wide in the middle and prone to burning the rider’s leg. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

The new bike, known as the RH67 was a single cylinder design with two exhaust ports and twin pipes like the popular CZ’s of the time. The power was still extremely peaky and difficult to ride. Suzuki was used to using seven and eight-speed transmissions on their road race bikes to get help get the most out of their narrow powerbands. When these high RPM motors were bolted to a four-speed transmission, the engines had a hard time pulling the wide gap between gears. When you combined difficult power with the subpar handling, the RH was just not up to competing with the European machines from Husqvarna and CZ. Hurting the RH’s handling was its dry weight of 235lbs. This was at a time when the best bikes in the class hovered around 210lbs. It was becoming quickly apparent that Suzuki needed to enlist some outside help to get their motocross project on track.

|

| A pristine TM250 like this one can cost a small fortune. The silver and blue paint scheme was a trademark of Suzuki’s race bikes in the early ’60s. There is little denying that the bikes looked a lot better than they performed. |

Perhaps the biggest news for consumers in ‘67 was Suzuki’s plan to actually sell a limited run of RH67 replicas to consumers. Dubbed the TM205, the all-new machine would be sold in very limited numbers (an estimated 200 total, with only 65 making their way to America). In appearance, the TM250 looked virtually unchanged from the RH works bike it sought to emulate. At first glance, it was a dead ringer, right down to the twin-pipe exhaust and fiberglass racing fenders.

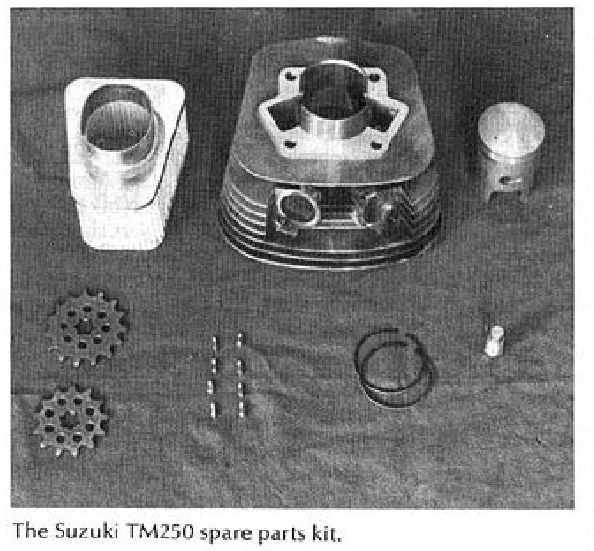

The TM250 motor featured a unique crank mounted clutch and undersquare 66x73mm bore and stroke producing a claimed 32Hp at 7800 RPM. As sold, the TM’s four-speed transmission shifted to the left and braked to the right, but a full length splined selector shaft exited on both sides, and the mirror imaged rear-brake controls were easily swapped from side-to-side. Every TM250 came with a complete parts kit that included pistons, rings, replacement clutch parts, gearing, and carburetor jetting. At $975 the bike was actually a bargain considering what the hand-built machine must have cost Suzuki to produce.

|

| Swedish motocross champion Olle Pettersson airs out the RH69 in Hollice, Czechoslovokia. Pettersson was instrumental in getting Suzuki’s new race program on track and headed in the right direction. |

The chassis on the TM250 was somewhat suspect with twitchy unpredictable handling. The wheelbase was an inch shorter than a contemporary Husky and prone to a great deal of frame flex. The forks were supposed to be “Ceriani-style” (Ceriani was a reputable European fork supplier at the time) but more closely resembled the forks from one of Suzuki’s street models in performance. The twin shocks on the TM were no better, banging and crashing around the track. The TM was definitely in need of a lot more refinement before it was ready to compete with the best from Europe.

|

| Every TM250 came with a complete parts kit that included a cylinder, pistons, rings, air cleaner, replacement clutch parts, gearing, and carburetor jetting. |

In 1967 Suzuki realized that if they were ever going to be able to beat the Europeans at their own game, they were going to have to hire a top rider to develop their bikes. In late 1967 Suzuki hired 30-year-old Swedish champion, Olle Pettersson, to help improve the machines. When Pettersson rode the new RH68 he declared the bike terrible and told the Suzuki engineers the whole bike had to be redesigned. He told them the chassis was too short, the bike was too heavy, the powerband was too narrow and the steering head angle was all wrong. Pettersson would prove to be not only a brilliant racer but also one of the finest development riders in the history of motocross. In a short six months, Pettersson steered the RH68 project away from the failed RH67 toward the incredible RH69. Once they added Pettersson, Suzuki was on the fast track to motocross success, and within three years the brand would sit atop the most prestigious motocross championship in the world.

|

| It would take Suzuki nearly a decade to produce a decent production motocrosser. The ’67 TM250 was a first attempt that probably did nothing to scare the established European brands. Little did they know this was only the first shot in a war that would bring most of the Old World brands to their knees. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

The 1967 TM250 while far from a world beater when new has become one of the most desirable collector bikes in motocross history. As the first of the Japanese invasion, the ultra-rare machine will always be remembered as a precursor to the domination yet to come. While it would be nearly another decade before Suzuki would introduce its incredible RM series and take the motocross world by storm, the TM250 sowed the seeds for a motocross dynasty.