For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at one of the forerunners of the modern four-stroke revolution, the 1986 Honda TR200R “FatCat”.

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at one of the forerunners of the modern four-stroke revolution, the 1986 Honda TR200R “FatCat”.

|

|

In 1986, Honda shocked the racing world with the introduction of their incredible new racing machine, the TR200R “FatCat”. The TR (Totally Radical) featured an ultra-compact four-stroke power plant, wrapped in works style bodywork and mated to an innovative new suspension system. It was a perfect example of the engineering prowess Big Red displayed during the 1980’s. |

In 1986, the AMA threw the sport of motocross a major curve ball with the introduction of the “production rule”. The regulation placed major limitations on the modifications that could be done to race bikes and dictated that all racers be based on off-the-shelf production machines. This meant an end to Honda’s super-exotic and super-expensive HRC race bikes. Now the big team’s race bikes would have to start out just like Joe Average’s scooter, instead of some skunk works special.

|

|

The man behind the TR200R project was Mugen founder Hirotoshi Honda. Always one to push the envelope of design, Soichiro Honda’s son was a champion of outrageous high performance machines. The eventual death of the “FatCat” project was a crushing blow to Hirotoshi. After the plug was pulled on the TR200R, Hirotoshi resigned from Mugen and made a fortune designing self-cleaning cat boxes. |

While the loss of the exotica at the races may have curbed some interest at the professional level, there is no disputing that the new focus on production performance improved the breed. With Rick Johnson and Jeff Ward forced to ride stock-production machines, it became ever more important to improve out of the crate performance. For Honda, this was especially important. They had dominated the “works bike” sweepstakes for years, and had no intention of loosing that technological advantage. With that in mind, Honda set about building the ultimate production racer for the ’86 season.

|

|

With the incredible success of the TR200R, Yamaha was quick to come out with a “big wheeled” racer of their own. The new BW200 was basically a poor man’s knock-off of the high tech Honda. One look at its old school dual shocks told you everything you needed to know. Lame. |

The genesis for the new bike would be the work of Mugen founder Hirotoshi Honda. After moving on from his pioneering work in the incredible Mugen ME125 in 1980, Honda had become interested in exploring the envelope of four-stroke performance. At the time, thumpers were still considered toys, but the brilliant engineer saw a lot of untapped potential in the valve and cam design.

|

|

When I switched from my venerable CR125 to the all-new TR200R, I went from singing the B Class blues to showing those spodes who was the BOSS. If not for an unfortunate injury while doing a Cycling East photo shoot (a phenomenon known as “Le Cobraing” in pit-punditry circles), I would have been the District 7 Open Class champion. |

Starting in 1984, a skunk works program was begun in Japan to develop the ultimate four-stroke race bike. No idea was too outlandish, and with the clout of Soichiro Honda’s son behind it, no expense too high. The new machine would go by the code name “TR” (as in “Totally Radical”), be a “no-compromise” race bike, and incorporate the very latest in racing theory into its design. The target weight would be 215 pounds (about 50 pounds less that a comparable XR200R), with a power output somewhere in the mid-forties.

|

|

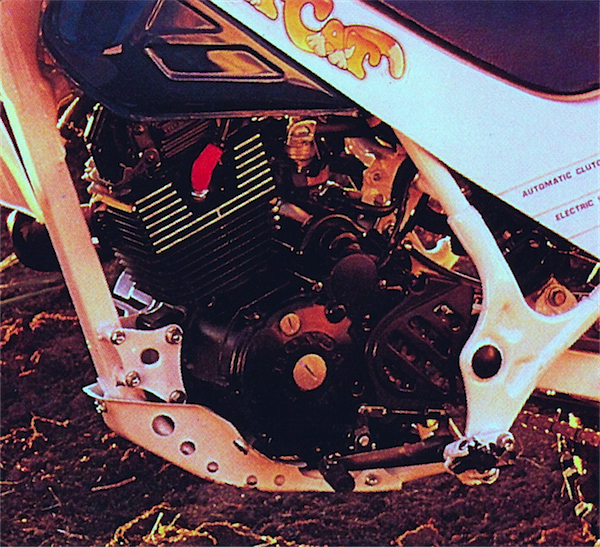

The short-stroke power plant used in the TR200R was a miracle of four-stroke technology in 1986. Using an early version of their patented Uni-Cam technology and a five-valve head, the 199cc mill revved to a stratospheric 16,000 rpm and cranked out close to 40 horsepower on the dyno. |

In an effort to meet the program’s target weight, early TR200 prototypes used titanium frames and carbon fiber bodywork. In the motor, Honda would pioneer the use of a super-lightweight ceramic composite for the piston and valves, while making use of titanium for the crankshaft and rod. In the top-end, Honda would use a very early version of their patented Uni-Cam design to activate 5 valves (2-intake, 3-exhaust). When later asked to comment on the usage of five valves instead the usual four for the TR, Hirotoshi Honda stated a motto that became a design directive for the TR project: “More is always better?” This directive, known internally as the PULP (People Unanimously Love Pastries) principle applied to every facet of the TR’s radical design. If three inches of travel was good, then 4.7 must be better, so the engineers would go about making that a reality. With the TR, bigger was always better.

|

|

The TR200R derived its peculiar nickname of “FatCat”, from creator Hirotoshi Honda’s pet feline Sinjin Noo Shiri (“ass of fat” in Japanese). |

Once Honda testers got their hands on the prototype TR200, it became apparent they were onto something. The ultra-lightweight bike was incredibly nimble and responsive. Its low-slung chassis gave the machine a planted feel and made cornering much easier than the skyscraper bikes typical of the day. In order to achieve acceptable suspension performance, while still hitting Honda’s target for a super low center of gravity, Honda made the innovative decision to go with a set of high floatation pneumatic tires for the TR. This meant that on top of the bike’s excellent 5.9 inches of mechanical travel, there was a further four inches of pneumatic travel, for total of nearly ten inches!

|

|

Cool features abounded on the TR200R. This super trick “up-the-tank” works style seat was stolen directly off Bob Hannah’s ‘85 RC250. |

The switch to high flotation Ohtsu’s from traditional motocross tires actually benefited the TR project in many ways. At first, the remarkable low-end torque of the 199cc five-valve Uni-Cam motor made accelerating out of tight turns difficult. The high revving mill tended to blast through the powerband with such ferocity that traditional tires could not keep up. The switch to the ultra-grippy Ohtsu’s provided much better feel and allowed the TR200 to out-pull Honda’s own CR500 out of turns on hard slippery surfaces. The TR rider would be hooked up and hauling, while the hapless 500 rider was forced to back off to fight wheel spin.

|

|

Few days in my life are as glorious as the day I brought home my very own TR200R. In order to get it, I had to place myself on a waiting list a full year before the bike was released and pay nearly twice the $1998 sticker price. It was all worth it, however. My racing career was transformed and I went from a nobody, to a local celebrity overnight. |

|

|

In the front, the TR200R used a combination of new and old technologies to provide stellar performance. The 22mm Showa cartridge forks absorbed the big hits, while the high floatation Ohtsu tires gobbled up the breaking bumps. This was the best front end in motocross in ’86. |

Another area where the Ohtsu’s shined was in Supercross. In ’86, Supercross tracks were very different than they are today. Back then, the tracks were not uniform and obstacles varied greatly from week-to-week. With triples often reaching 70-80 feet in distance, it was very hard for riders to even clear the massive leaps at times. Then in ’85, while doing durability testing, team rider Ron Lechien found that the added bounce from the Ohtsu’s on takeoff provided an additional 29 feet of distance off the Himalayas (a phenomenon known as the “Moser Effect” in engineering circles). This, combined with the additional traction of the wide contact patch, made previously impossible jump combinations a piece of cake. Ironically, Lechien would never get to race the TR200R. Honda apparently neglected to get the Dogger to sign his new contract (a situation known in business circles as the Chiz gambit) and as a result he made the jump to Kawasaki for the ’86 season.

|

|

Even though the TR200 provided quick revving and a brutally fast spread of power, it did not skimp on convenience features. Electric starting was standard (20 years before the KTM 450SXF) as was a slick automatic clutch. |

Unfortunately, by the time the TR200R “FatCat” (so named for Hirotoshi Honda’ s favorite petSinjin Noo Shiri, which translates to “ass of fat”) made production in ’86, some compromises had to be made. The super lightweight titanium frame that made the bike so light and responsive in pre production was found to snap in half at the slightest provocation (a phenomenon known to metallurgists as “Pinging”). This meant a switch to heavy, but durable pig iron for the production frame. Likewise, the ultra-trick carbon fiber bodywork was found to shatter into sharp pieces on hard landings and eviscerated several test riders, resulting in a switch to plane old plastic for production.

|

|

The keys to the incredible success of the TR200R project were these specially made super high traction tires. Early prototypes of the TR used traditional skinny Motocross tires, but they were found to be insufficient at harnessing the incredible power of the TR. Because of this, Honda commissioned tire maker Ohtsu of Japan to make these “one-off” super-wide contact patch tires for the project. Once they were installed, performance history was made. They were found to be such an advantage (much like the paddle tire of Jimmy Weinert), that the AMA banned them from competition after a mere two seasons. |

The awesome motor was still in place, but once the production engineers had their way, the horsepower figures plummeted. On the dyno, the pre-pro motor had cranked out close to 48 hp, but the switch to a milder cam, low compression head (to run on pump gas) and a EPA legal exhaust (an odd edition on such a race oriented machine) pulled that figure down to the mid-thirties (still comparable to a CR250R in ’86). The high-tech motor did incorporate several cutting edge features for the time. Think your KTM 450SXF is trick with it’s electric starting? Think again- the TR200R had it in ’86. How about James Stewart and his “hush-hush” Rekluse style auto clutch in his Factory RMZ450? Nope, the TR200R had it in ’86. On the TR, all a rider had to do was hit the magic button, pin the throttle, and start slamming in those gears; the bike did the rest.

|

|

In the rear, the TR200 went with a high tech “no-link” rear suspension system, mated to a works style piggyback Showa shock. The shock featured 45-way compression and rebound settings, which combined with the adjustable tire pressure to provide nearly infinite adjustability. Honda once again went with the drum brake off the 83 RC250 for the rear binder, only this time it featured dual actuation. Apparently, test riders waffled about whether they liked the traditional foot activated lever or a bar mounted setup better (a phenomenon known in professional rider circles as “Thomasing”), so Honda just went with both. |

In the suspension department, the TR200 was like cheating. Its ultra-compliant Ohtsu meats took care of eating up the small stuff, while its 22mm works style Showa cartridge forks and Showa piggyback shock gobbled up the big hits. With the high floatation tires, mud was never a concern and if you got pulled on the start, it was your mistake. Into the first turn, those big, wide tires made grabbing the inside easy. Stopping the TR was also a breeze, as its incredibly wide contact patch made out braking the competition a piece of cake. The added traction was such an advantage, that Honda realized they could save valuable ounces by fitting ultra-low weight drums in place of the larger and heavier discs common at the time. Honda had proven the these binders in ’83 on the RC250’s of Bailey and Hannah and decided they would be an advantage on the TR. Considering how many races are lost every year to bending a fragile disc rotor, its hard not to see Honda’s reasoning for sticking with the proven technology.

|

|

With Rick Johnson at the controls, the TR200R was nearly unbeatable in the mid-eighties. It dominated Supercross and outdoors for two years, before unceremoniously being banned by the AMA. Even today, Rick Johnson won’t stop talking about those four titles (a phenomenon known in professional bench racing circles as “Matthesing”). |

Ultimately, the story of the TR200R is a sad one. After dominating motocross and Supercross racing in ’86 and ’87 (and a failed attempt by Yamaha to copy its success), the TR was banned from AMA racing for the ’88 season. Its radical design and unbeatable combination of four-stroke power and Velcro-like traction were deemed too much of a competitive advantage. Once again, the deep pocket of Honda had caused its competitor to cry foul, and after a season-and-a-half of complaining, the AMA moved in. As a result, in ’88, Honda discontinued the TR project and with it, the promise of a truly high-tech racing four-stroke. It was another sad case of what might have been. After the failure of the TR200R, it would take Honda nearly two decades to once again wade into the racing four-stroke waters.

Hope you enjoyed this April 1st column!