For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s KX500 for 1990.

While the 1990 Kawasaki KX500 lacked the perimeter frame cachet of its smaller siblings, it made up for it by being one beastly good motorcycle. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the 1990 Kawasaki KX500 lacked the perimeter frame cachet of its smaller siblings, it made up for it by being one beastly good motorcycle. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

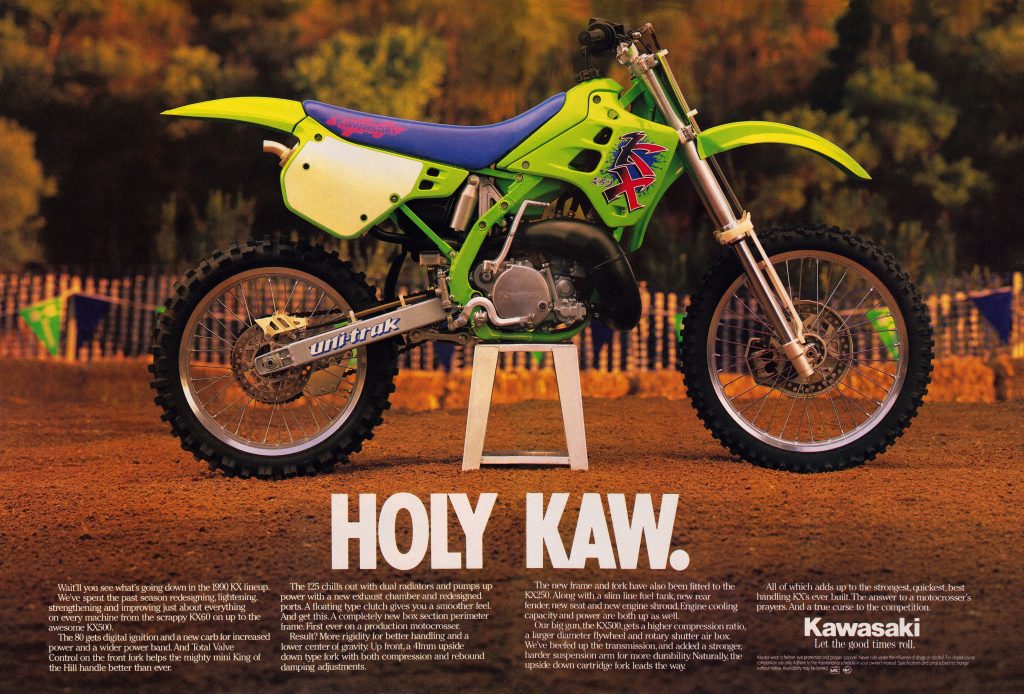

For Kawasaki motocross enthusiasts, 1990 stands as a major watershed year for the brand. After two decades of stodgy and somewhat off-beat designs, the Green Team shed their conservative reputation with the introduction of two of the most exciting and anticipated releases of the decade. All-new from the ground up, the 1990 KX125 and KX250 broke significant ground in styling and design and proclaimed to the world that Kawasaki was no longer content to allow Honda to capture the lion’s share of the press’s adoration in the 125 and 250 divisions. Radically styled and boldly engineered, the 1990 KX125 and KX250 were the perfect machines to kick off Kawasaki’s 1990s motocross Renaissance.

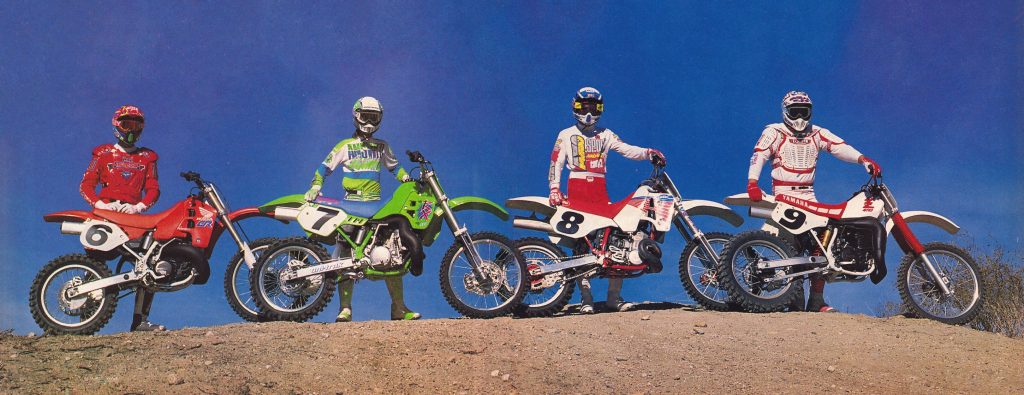

Once the premier division in motocross, the Open class had dwindled to only a few contenders by 1990. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Once the premier division in motocross, the Open class had dwindled to only a few contenders by 1990. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

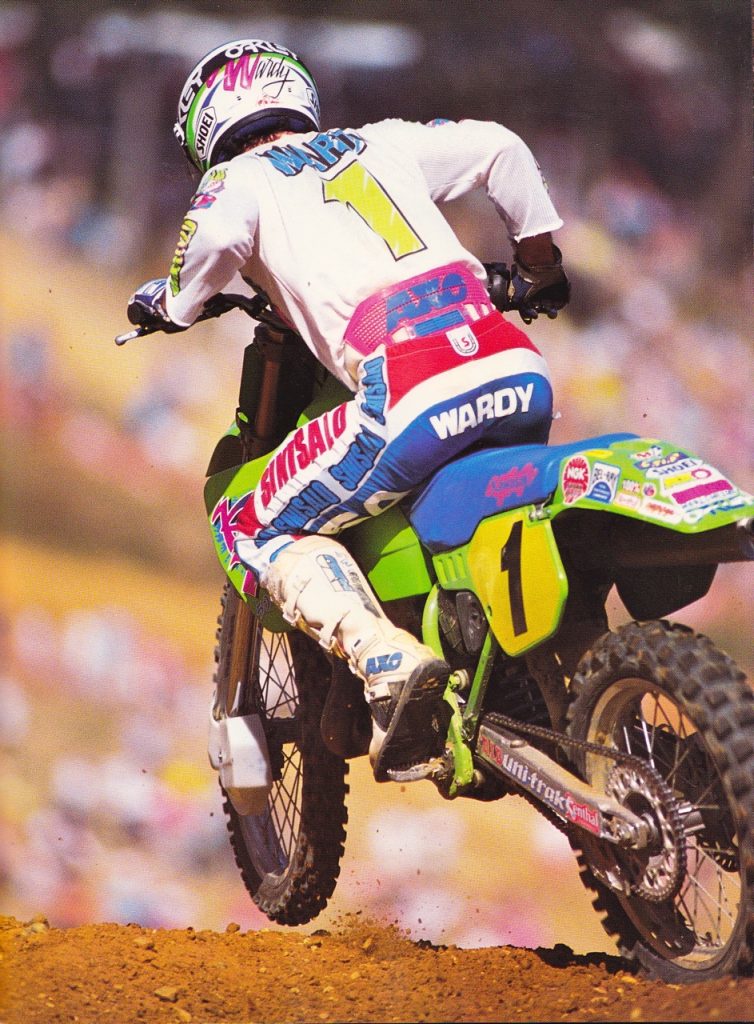

While the all-new KX125 and KX250 garnered all the attention in 1990, the best machine in Kawasaki’s lineup was far less of a matinee idol. In 1989, the KX500 had been the consensus pick as the best machine available in the 500 class. Its Rubenesque proportions were somewhat controversial, but its supple suspension and incredibly broad power were loved by all. While the CR was sexier with its new “low boy” layout and inverted forks, the KX was a far better racing machine. The Kawasaki’s power valve-equipped motor produced a long and very strong flow of power that was far less tiring than the red brute, and its “old-fashioned” 46mm conventional forks ran rings around the Honda’s high tech but highly flawed 45mm inverted Showa units. For the majority of 500 pilots (including 500 National Motocross champion Jeff Ward), the KX500 was a better machine.

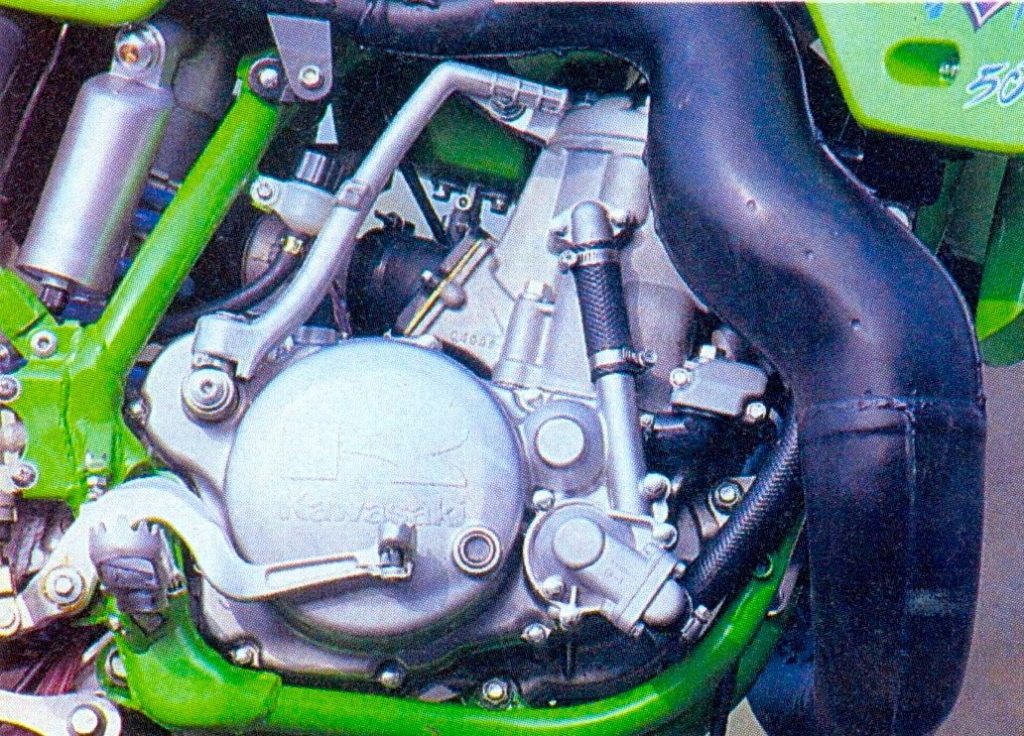

The addition of the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS) to the KX500 complicated maintenance, but also helped give the KX500 the widest and most-usable powerband in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The addition of the Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS) to the KX500 complicated maintenance, but also helped give the KX500 the widest and most-usable powerband in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

By 1990, the 500 class was no longer thought of as the premier division in motocross. Once the home of megastars like Roger De Coster, Heikki Mikkola, Brad Lackey, Broc Glover, and David Bailey, the 500 class had slowly declined in stature throughout the eighties. In 1984, Suzuki had pulled out entirely and by 1990, Yamaha’s aging and outdated YZ490 was on life support. In 1988, Kawasaki had fully redesigned their KX500 and in 1989, Honda had seen fit to give the CR500R what would turn out to be its last significant refresh. Dreams of a liquid-cooled YZM500-based YZ500 never materialized and most were left wondering about the long-term health of the big bore division.

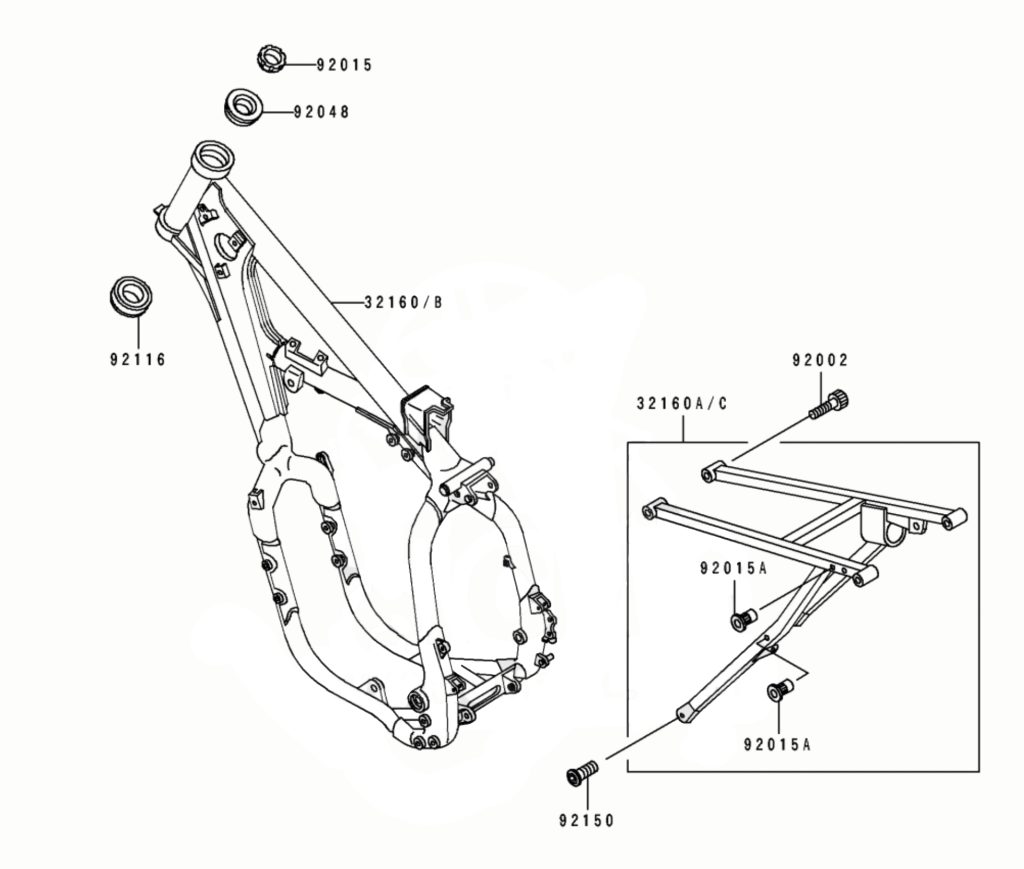

The only significant change to the KX500’s frame for 1990 was some additional bracing added to the steering stem to improve the chassis feel and cope with the added stress of the new stiffer inverted forks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The only significant change to the KX500’s frame for 1990 was some additional bracing added to the steering stem to improve the chassis feel and cope with the added stress of the new stiffer inverted forks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1990, Kawasaki chose to focus on refinement rather than reinvention on their KX500. Already the best machine in the class, the KX could afford a year of minor updates while the little bikes garnered all the press. There was still a good deal of hope that future editions would get the perimeter frame and Buck Rogers bodywork, but for 1990 the KX500 was left to make do with a fairly modest list of updates.

The release of the all-new perimeter framed KX125 and KX250 brought Kawasaki a huge amount of press and consumer interest in 1990. At the time, many expected the KX500 to get the perimeter treatment in 1991 or 1992, but this much-anticipated change would never make it to the big-bore machine. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The release of the all-new perimeter framed KX125 and KX250 brought Kawasaki a huge amount of press and consumer interest in 1990. At the time, many expected the KX500 to get the perimeter treatment in 1991 or 1992, but this much-anticipated change would never make it to the big-bore machine. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Chief among the changes for 1990 was a switch from Kayaba’s much-heralded 46mm conventional cartridge fork to their new 41mm inverted design. In 1989, the full-size KX models had all originally been slated to receive this change but feedback from US test riders had led Kawasaki USA to ditch the unproven forks on US-bound models and instead go with a version of the works conventional units Jeff Ward and Ron Lechien had used in 1988. The switch turned out to be a masterstroke and the 46mm KYBs helped propel Kawasaki to the front of the 1989 suspension standings.

In 1990, Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward would roost the mighty KX500 to his second consecutive 500 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1990, Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward would roost the mighty KX500 to his second consecutive 500 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1990, it was felt that the 41mm inverted forks were finally ready for prime time and they bolted to the front of all three full-size Kawasaki machines. The new forks were slightly longer (10mm) for 1990 and required a different offset and modified pull-rod in the Uni-Trak linkage to maintain the old machine’s chassis balance. In addition to new clamps, the frame was also strengthened at the steering stem to compensate for the stiffer front fork tubes. The new forks offered 12.2 inches of travel and featured 23 compression and 20 selectable rebound settings.

A bit of added weight to the flywheel, a slight bump in compression, and a beefed-up transmission were the big changes on tap for the KX500 mill in 1990. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

A bit of added weight to the flywheel, a slight bump in compression, and a beefed-up transmission were the big changes on tap for the KX500 mill in 1990. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

In the rear, the KX500 employed the same KYB shock as 1989 but the Uni-Trak linkage was upgraded from cast to forged aluminum construction for greater strength and improved durability. Overall travel remained at 13 inches and the shock offered 16 positions for compression and rebound adjustability. In addition to the beefed-up linkage, the new KX swingarm featured an upgrade to the axle bracket designed to increase strength and simplify chain adjustments.

While the KX500 lacked the curb appeal of its sexy smaller brothers the old-fashioned chassis turnout to be the best-handling package in the Kawasaki lineup. Turning was precise for a big machine and the KX was content to blast across the Open desert with nary a wobble or whimper. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While the KX500 lacked the curb appeal of its sexy smaller brothers the old-fashioned chassis turnout to be the best-handling package in the Kawasaki lineup. Turning was precise for a big machine and the KX was content to blast across the Open desert with nary a wobble or whimper. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Aside from the additional gusseting at the steering stem, the KX500’s frame was unchanged for 1990. It did not get the perimeter layout of the smaller machines, but that was not entirely a bad thing. The new perimeter frames were very wide and tall and that gave the bikes a rather top-heavy feel. There was also a limited amount of space between the frame spars and that made it difficult to add fuel capacity without drastically altering the machine’s ergonomics. The KX500’s more traditional frame avoided both of these issues and allowed the big Kwacker to handle very well despite its large tank, wide midsection, and monster motor. The new stiffer front end noticeably improved steering precision and the 500 was easily the best-handling machine in the 1990 KX lineup. There was none of the floppy front end or instability found on the perimeter machines. Instead, the Jolly Green Giant just followed its intended line as expected and set sail for the horizon like a bullet train headed for Tokyo. In the turns, the big KX was not as nimble as Honda’s razor-sharp CR500R, but it was more than capable of changing direction. The steering was fairly quick, and the front end could be trusted more than the slightly unpredictable KX250. As long as you did not try to ride it like a 125 and pin it to the stops, the KX500 was an excellent-handling big bore machine. Just keep the revs low, flow the turns, and count on that luscious torque to pull you through.

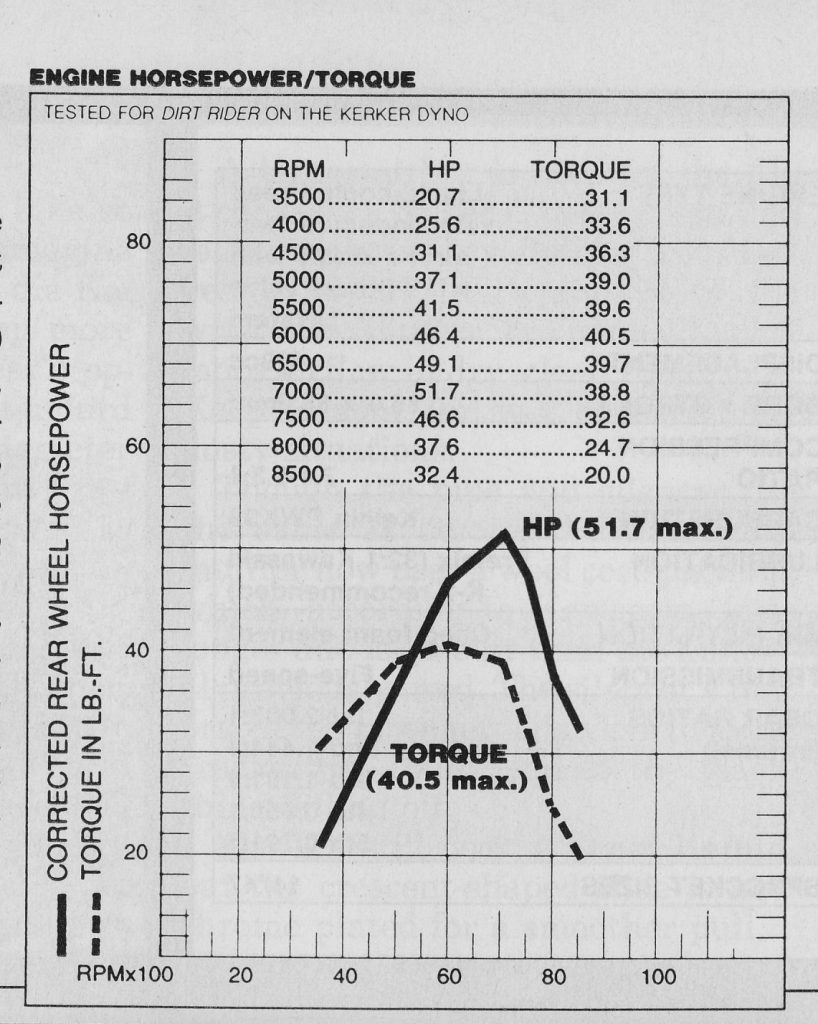

The King of twist: Today, a modern 250F can match the horsepower output the KX500 displayed in 1990 but even a fuel-injected 450 four-stroke can’t touch the massive 40 foot-pounds of torque the stock KX500 put to the ground. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The King of twist: Today, a modern 250F can match the horsepower output the KX500 displayed in 1990 but even a fuel-injected 450 four-stroke can’t touch the massive 40 foot-pounds of torque the stock KX500 put to the ground. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the motor front, the name of the game for 1990 was once again “refined”. With the only power valve in the class, the KX500 already possessed a significant technological advantage over its rivals. The KIPS system allowed Kawasaki to smooth out and broaden the power of their 499cc brute and the KX500 offered what was considered at the time to be the perfect Open class powerband. For 1990, Kawasaki further polished the power on the KX by enlarging the flywheel slightly, narrowing the head gasket, and increasing the capacity of the air filter. The center cases were increased in strength and two of the transmission’s five speeds were beefed up for improved durability. Lastly, they redesigned the silencer bracket to be less brittle and added the ’89 KX250’s rotary shutters to the airbox to allow for more or less air to be let into the box depending on track conditions.

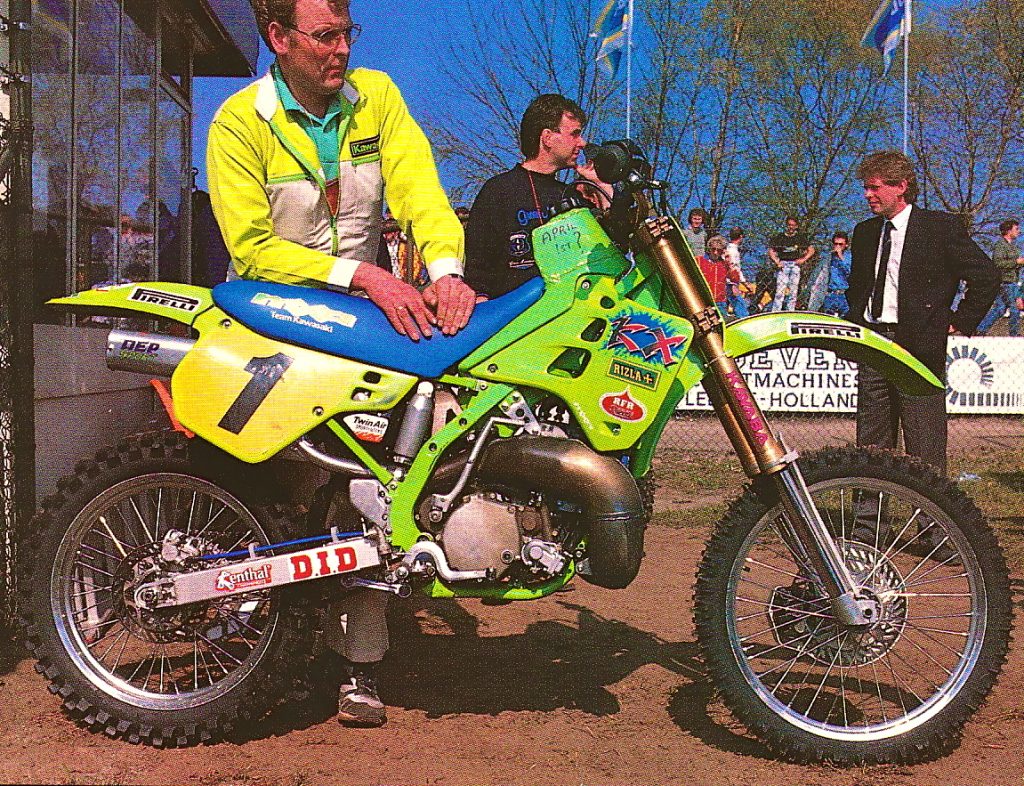

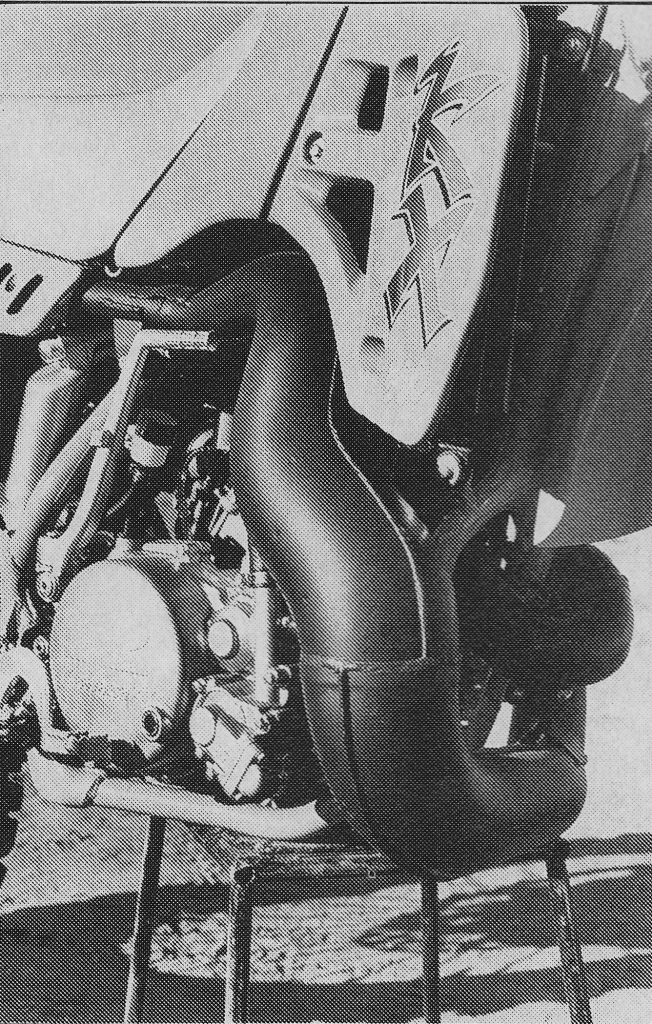

Kawasaki did race a works perimeter-framed SR500 in Europe during the 1990 World Championship, but the bike never made it to production. Defending 500 champion Dave Thorpe was not happy with its performance and switched back to the traditional chassis mid-season. Perhaps this interesting attempt to add more fuel capacity had something to do with his dislike for the machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Kawasaki did race a works perimeter-framed SR500 in Europe during the 1990 World Championship, but the bike never made it to production. Defending 500 champion Dave Thorpe was not happy with its performance and switched back to the traditional chassis mid-season. Perhaps this interesting attempt to add more fuel capacity had something to do with his dislike for the machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the track, the 1990 Kawasaki KX500 put out the kind of power that brings home championships. Very few machines in history have been able to achieve the 1990 KX500’s incredible combination of ease of use and absurd power. Chug it, lug it, or rev it to the moon, the KX’s motor did not care. Unlike the CR500R, which was always in danger of exploding violently forward if the throttle was applied injudiciously, the KX could be trusted to give you just want you wanted and never too much. The power was silky smooth and always there waiting to be called upon. Almost like a modern 450 four-stroke, the 1990 KX500 offered a powerband a mile wide with more than enough thrust to conquer any obstacle. There was none of the thumper’s compression braking and a ton more vibration, but the overall feel of always having more than enough power was there.

The new 41mm inverted forks on the 1990 KX500 improved steering precision and did an admirable job of smoothing out the track. In stock condition they were a bit soft, but once you upgraded the springs, they were the best forks in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The new 41mm inverted forks on the 1990 KX500 improved steering precision and did an admirable job of smoothing out the track. In stock condition they were a bit soft, but once you upgraded the springs, they were the best forks in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Off the track, the KX was even more of a winner with its smooth delivery paying major dividends off-road. It was far easier to control than the hard-hitting Honda and Yamaha and less tiring to ride. The YZ490 did have its devotes due to its lack of radiators to damage, but its vibration, pinging, and high-strung powerband made it less attractive unless a claw-hammer simplicity was your only concern. The KX’s excellent stability also played a factor off-road where the speeds were likely to flirt with triple digits. Here the CR’s quick handling was more of a hindrance than a blessing and the KX made a far better desert sled than its red rival.

The stock shock on the KX offered a smooth and compliant ride that easily outclassed the performance of its rivals. Suspension performance is critical on a big and powerful machine and the KX had the area covered in 1990. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The stock shock on the KX offered a smooth and compliant ride that easily outclassed the performance of its rivals. Suspension performance is critical on a big and powerful machine and the KX had the area covered in 1990. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1990, this 499cc beast was the most advanced motor in the 500 class. Smooth, broad, and blessed with a nearly endless pull, the KX offered the perfect Open class powerband. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1990, this 499cc beast was the most advanced motor in the 500 class. Smooth, broad, and blessed with a nearly endless pull, the KX offered the perfect Open class powerband. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the suspension front, the KX500 was once again excellent on track and off. In stock condition, the forks were slightly soft and perfect for off-road use. Small chop was gobbled up in stride, but stiffer springs were advisable for heavier or faster riders. With a spring swap and some dial spinning, the new 41mm inverted forks offered the smoothest ride in the class. They easily outclassed the harsh units found on the CR and were more than a match for the outdated 43mm conventional units found on the YZ. Some riders still thought the 1989’s 46mm conventional units may have been better, but overall, the increase they provided in steering precision was felt to be a more than fair tradeoff.

The Open class of 1990 offered quite a variety of weapons to choose from. The KX and CR were the best choices for motocross, while the KTM and Yamaha made excellent off-road mounts. Of the four, the Kawasaki did the best job of bridging these two disciplines and providing a machine that could excel on the track and off. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The Open class of 1990 offered quite a variety of weapons to choose from. The KX and CR were the best choices for motocross, while the KTM and Yamaha made excellent off-road mounts. Of the four, the Kawasaki did the best job of bridging these two disciplines and providing a machine that could excel on the track and off. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, the situation was equally excellent with the Uni-Trak once again providing the smoothest action in the class. Damping and spring rates were well-suited to motocross and fast off-road use and the KX could easily be dialed in for a wide variety of skill levels. Bottoming was not an issue and the Kawasaki offered a plush ride that easily outclassed the harsh Honda and geriatric Yamaha. All three could be raced with the stock shocks in place but once the track got rough the superior action of the KX’s KYB damper pulled it ahead by a wide margin.

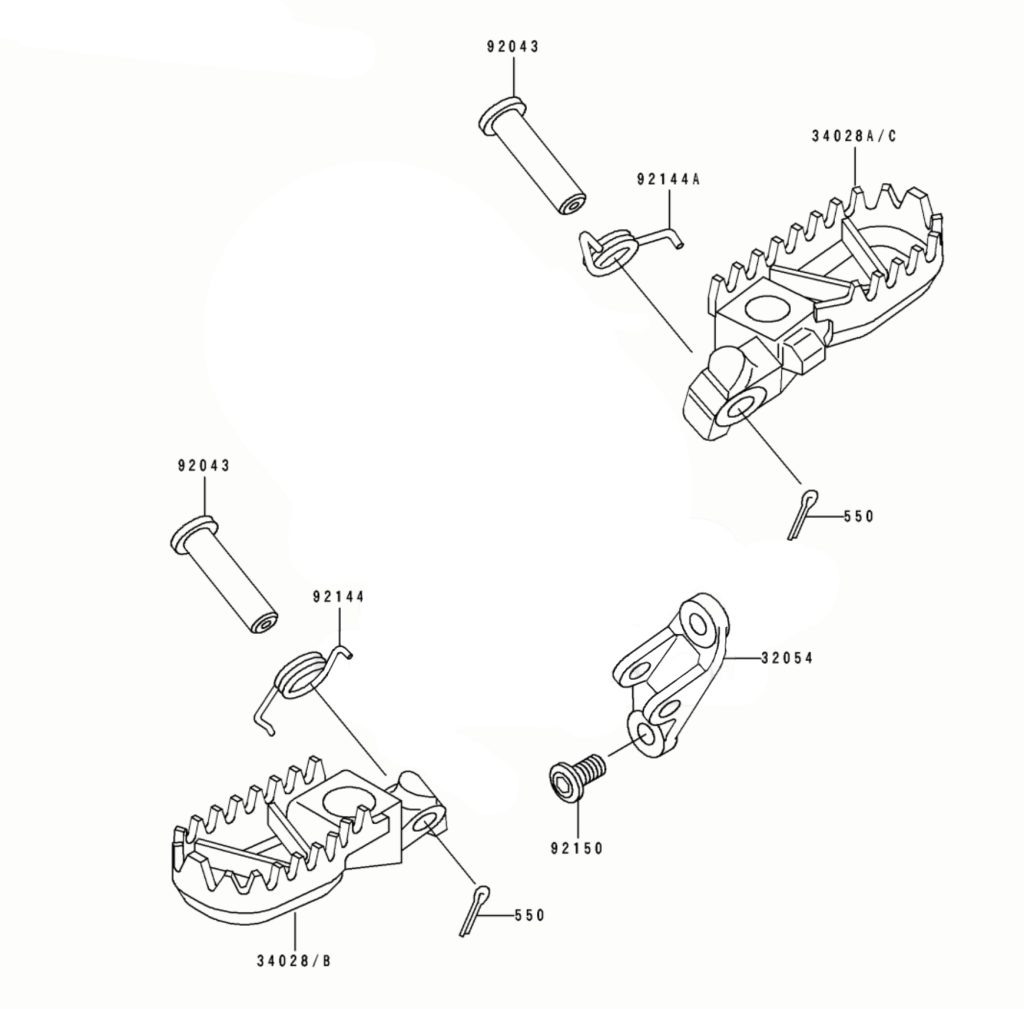

The KX500’s all-new ultra-wide pegs for 1990 were loved by all but the failure-prone return springs were less of a hit. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The KX500’s all-new ultra-wide pegs for 1990 were loved by all but the failure-prone return springs were less of a hit. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the detailing front, the KX500 continued to be a step behind its red rival in 1990. The KX’s brakes, while powerful, were grabby and harder to modulate than those found on the CR. They also required bleeding far more often to maintain their performance. The new seat foam for 1990 was stiffer, but the KX’s seat continued to feel like sitting on a big marshmallow. This tended to lock you in place and only exacerbated the KX’s large and old-fashioned feel. The new color scheme and graphics for 1990 updated the bike’s stodgy appearance somewhat, but the big Kwacker’s boxy and oversized bodywork continued to make it look and feel like your father’s Oldsmobile when compared to the sexy Honda. In addition to being terminally boring, the KX’s bodywork continued to be more brittle than the competition as well. Any slight tip-over was enough to crack a radiator shroud and over-tightening the gas cap was likely to leave you with a lap full of 92 octane. The bolts and nuts were also of poor quality and far less durable than the hardware found on the CR. Of particular concern were the KX’s seat bolts which were easy to snap and even easier to strip out. The footpeg springs were also utter junk and prone to going missing at inopportune moments. At least the footpegs themselves were excellent and easily the widest and most comfortable found anywhere in the sport.

By 1990, Open class bikes had fallen out of favor as the premier machines for motocross but they still made excellent machines for play riding in the hills. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

By 1990, Open class bikes had fallen out of favor as the premier machines for motocross but they still made excellent machines for play riding in the hills. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Overall motor reliability was great but the KX did like to foul plugs if ridden timidly. This was more of an issue when riding off-road and it was best to keep a spare or two in your fanny pack. The KIPS system seemed to allow the bike to load up when ridden at low rpm for extended periods and it was not always happy to clean out once the throttle was finally whacked open. This was much less of a problem on a motocross track and generally, the KX carbureted well once you leaned out the pilot circuit a bit.

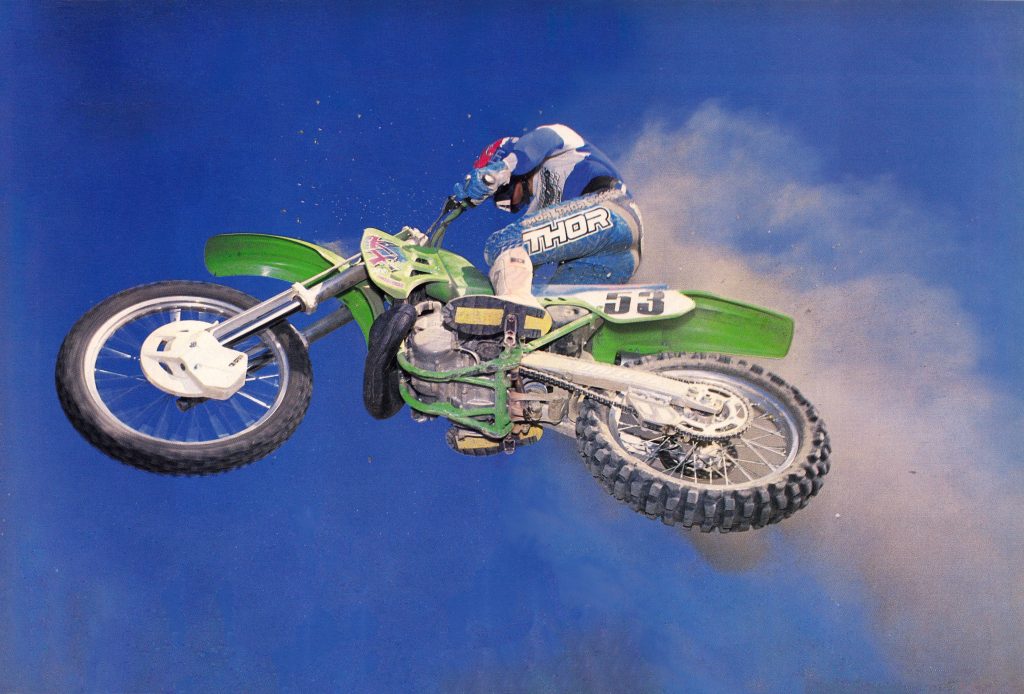

Big air was the KX500’s forte in 1990. It had the motor to bridge any gap and the suspension to handle the landing once it was time to touch back down. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Big air was the KX500’s forte in 1990. It had the motor to bridge any gap and the suspension to handle the landing once it was time to touch back down. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

While 500s typically do require far less maintenance than smaller machines, it is worth noting the added complexity the KIPS system added to the KX. This was one of the factors that continued to drive sales of the outdated YZ490 and there was no denying that the KX was the most complicated of the remaining Japanese 500s to rebuild. Thankfully, however, taking apart the big KX was rarely necessary. The motor was stone ax reliable and most riders could race a whole season without pulling it down for a rebuild.

In 1990, there were certainly sexier machines available than the KX500 but very few of them were as accomplished at their intended mission as Kawasaki’s big green pussy cat. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

In 1990, there were certainly sexier machines available than the KX500 but very few of them were as accomplished at their intended mission as Kawasaki’s big green pussy cat. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

Overall, the 1990 Kawasaki KX500 turned out to be a truly winning package. Without the fanfare and excitement heaped upon its little brothers, it flew under the radar to become the most-effective machine in the Kawasaki lineup. Awesomely powerful, well suspended, and excellent handling, the 1990 KX500 was the ultimate Open class weapon in 1990. While not as slim and sexy as some of its rivals, the KX had them covered in the categories that mattered most. Big, bad, and built to win, the 1990 Kawasaki KX500 was a bike that placed function over flash and continued to rule on the track and in the desert for the better part of a decade.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com